A Strategic Assessment of Technology Denial Regimes

Strategic Effectiveness and Adaptive Responses in Relation to Technology Denial Regimes

Authors

Executive Summary

This document has been formatted to be read conveniently on screens with landscape aspect ratios. Please print only if absolutely necessary.

Arindam Goswami is a Research Analyst with the High-Tech Geopolitics programme at The Takshashila Institution, Bengaluru.

Technology denial regimes are at present being used as key tools in geoeconomic statecraft; but their success depends on several factors that rarely come together. This paper looks at why these regimes work (or fail) by studying historical examples in the nuclear, space, defence, and computing sectors. It pays special attention to the current US-China rivalry in the realms of semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

The research shows that technology denial works only under very specific conditions: when supply chains are tightly controlled by several countries working together, when targeted countries cannot easily adapt or build up their own capabilities, and when there are no alternative partners. It finds that countries like India can turn denial into long-term advantages by enhancing their own capabilities.

The analysis further identifies several asymmetric capabilities that both sides can use beyond standard export controls. These include monitoring supply chains for information warfare, influencing standards, limiting access to financial systems, attracting skilled workers, and investing in new breakthrough technologies. For imposing countries, the research recommends focusing on narrow, critical technologies rather than broad-based controls, maintaining robust multilateral coordination, and incorporating adaptive feedback mechanisms with regular reviews. For targeted countries, the optimal strategy combines sustained indigenous R&D investment, supply chain diversification, coalition building with similarly constrained countries, and strategic focus on emerging technologies that enable leapfrogging rather than mere replication.

The author would like to thank Pranay Kotasthane for his valuable comments and feedback.

The paper concludes that the main effect of technology denial may not be stopping rivals from advancing, but instead splitting global technology markets and speeding up the creation of new alternatives. This split can actually make targeted countries stronger in the long run, as they build their own innovation systems that can compete globally. The US-China tech rivalry will likely end with a lasting split of the global technology market into separate groups.

1. Introduction

Technology denial is now a key part of global competition. As countries use supply chains as tools and block access to important technologies, it is crucial to question the effectiveness of these restrictions. Do export controls really stop determined rivals from gaining new abilities, or do they just push them to become more independent?

This discussion document looks at technology denial regimes in a new way. Instead of seeing them as fixed policies, we view them as ongoing contests between countries—with each side adapting its strategies over time. Using decades of history from fields like nuclear, space, defence, and computing—we build frameworks to show when denial works well, and when it fails badly.

The paper begins by exploring, in section 2, theoretical foundations that explain why technology denial works in some contexts but collapses in others. It looks at insights from realist international relations theory, strategic trade policy, and innovation economics to identify the core mechanisms that determine effectiveness. This theoretical groundwork sets the stage for two analytical frameworks which are discussed in sections 3, 4 and 5: one assessing denial regimes from the imposing country’s strategic perspective, weighing supply chain control against multilateral cooperation; the other evaluating targeted country’s adaptive resilience, based on indigenous capabilities and alternative partnerships.

These frameworks then materialise into practical decision-making flowcharts in section 6 that both imposing and targeted countries can employ when navigating technology restrictions. The paper then provides a few policy prescriptions in section 7 based on this analysis. It also looks at less familiar tools that go beyond standard export controls. These include information warfare, using financial systems, attracting talent, and new technologies that can change the game. These unconventional methods may have a bigger impact than formal restrictions.

In section 8, the paper—by combining history and theory—predicts that current US restrictions on China in semiconductors and AI will likely speed up China’s push for independence. This, in turn, will alter global innovation in ways that those who designed the controls did not expect.

Finally, applying the frameworks introduced in this document, multiple case studies have been analysed in the Appendix, examining technology denial across diverse sectors to extract sector-specific lessons while identifying universal principles.

2. What makes Technology Denial Regimes effective

The answer to this question would vary according to the context and objectives of each denial regime. The objectives themselves could range from outright long-term denials, to delaying the acquisition of technologies in the short term to get countries to the bargaining table, to graded regimes, and so on. Effectiveness of technology denial regimes, therefore, would have to be measured by the imposing countries against their stated (or unstated) objectives.

There are some theoretical frameworks that are beneficial in analysing the effectiveness of such regimes. Let’s look at some of them below.

Technology denial regimes fall under the broader umbrella of strategic trade policy and economic statecraft.1 Various disciplines such as international relations theory, economics, and strategic studies can shed light on these. Realist perspectives, as articulated by scholars like Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer,2 identify the importance of technology denial in maintaining relative power advantages and deterring future rivals. States—as stipulated in offensive realist theory3 —aim to maximise their relative power, and exercising control over access to vital technologies is one mechanism for preserving strategic superiority.

The Wassenaar Arrangement was set up in 1996 and, while it gets less attention than the NSG or MTCR, it is probably one of the broadest export control systems. It covers conventional weapons and dual-use items such as advanced materials, electronics, and software. Wassenaar replaced the old COCOM system from the Cold War and brought in Russia as a founding member, which was a political compromise. This has caused issues because the group’s consensus rule lets any member block updates to the control lists. As a result, adding new technologies like advanced surveillance software and cybersecurity tools has become more difficult. This example shows that the way multilateral groups are set up can sometimes make them less effective over time.

Liberal institutionalist theories, borrowing from Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye,4 emphasise the central role of multilateral collaboration and regime creation in facilitating effective implementation. The complex interdependence theory5 would lead us to anticipate that technology denial regimes function best by operating through pre-existing international institutions, and involving multiple actors with aligned interests.

Enforcement is one of the greatest challenges, especially to technologies that can be readily disguised or modified. The international scope of technology markets requires that enforcement activities be coordinated across several jurisdictions, with varying legal systems and enforcement capacity. This requirement for coordination offers opportunities for evasion and makes it prone to inconsistent implementation. The efficacy of enforcement hinges on international information sharing, harmonised regulations, and proactive inter-agency coordination.

Denial regimes of technology have profound economic implications for the involved parties. For the imposing countries, such regimes can assist in preserving competitive advantages in key sectors, but at the same time pose the risk of fragmenting global markets and diminishing the economic gains of international cooperation. The advantages of denial regimes need to be offset with the disadvantages of decreased economic efficiency and countermeasures.

More recent analyses of technology denial emphasise the multifaceted nature of the contemporary supply chain, and the challenges this presents for control. Unlike the bipolar Cold War era, the present multipolar world has numerous channels for technology transfer, making absolute denial much more difficult to achieve. Furthermore, the fast pace of technological advancements means that new technology spreads within a span of just a few years, thus limiting the temporality of regimes of denial. Theoretical works by writers like Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman on weaponised interdependence6, provide insightful views on the means by which states may apply network effects and structural leverage within foreign supply chains in order to achieve strategic objectives through technology denial. According to the theory, states can use their location within global networks to coerce other actors, but ultimately this will fragment global systems and create alternative networks that erode the coercing state’s structural power over time.

The long-term efficacy of technology denial regimes depends largely on their capacity for adaptation to shifting technological and geopolitical conditions, as shown by the history of nuclear and space technology limitation over the past several decades. Technologies that are cutting-edge today may become widely available within a few years, while requiring constant updates to restriction lists and enforcement mechanisms.

Technology denial can have immense economic costs for targeted countries in terms of lost access to advanced technologies, increased costs of alternative options, and huge investments in indigenous development. These costs should, however, be balanced against the possible long-term gains of establishing more technological independence and decreasing reliance on possible untrustworthy suppliers. When target countries can successfully develop indigenous substitutes—or substitute supply networks—their reliance on hegemonic countries’ technologies is irreversibly reduced.

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957, the US responded by investing heavily in space and science. This led to NASA’s creation, changes in science education, and the Apollo program. There is a paradox here: the country that feels most threatened by a rival’s breakthrough often ends up changing itself more than the rival does. We are seeing this again today. Worries about China’s advances in AI and semiconductors have pushed the US to pass the CHIPS Act and boost federal research funding. This shows that technology competition can drive innovation in the country setting the controls as much as in the country being targeted.

The same trends apply to India’s space sector. Based on theoretical accounts of disruptive innovation theory,7 this example lends support to the proposition that constrained alternative solutions can eventually outperform established options. The theoretical model of technological paradigm shifts, advanced by authors such as Giovanni Dosi,8 predicts that deep shifts in technological orientation have the potential to quickly render these control measures obsolete.

The defence technology sector has another pattern of long-term development. The security complex theory conceptual framework—as developed by Barry Buzan and Ole Waever9—would expect regional security relations, and the necessity for self-sufficiency in defence capabilities, to put strong incentives for native development into motion that are capable of transcending external constraints in the long term.

The political sustainability of technology denial regimes is also worth careful examination, particularly in democratic countries where public support can shift with the passage of time. Popular support for such restrictions will gradually fade over a period of time, particularly if the costs continue to accrue while benefits are intangible. International support may also be lost if the regimes prove to be unjust or global conditions alter.

The hegemonic stability theory speculates that technology denial regimes must receive frequent assistance by the leading powers in order to be effective, and that changes in power distribution can lead to regime collapse or transformation. India’s ultimate entry into civilian nuclear commerce via the 2008 US-India Civil Nuclear Agreement10 is an example of the dynamic nature of technology denial regimes, and their potential to evolve over time. This case illustrates the theoretical observation of regime theory, which states that institutions have to evolve with changing situations if they are to remain effective and legitimate.

The biotechnology industry illustrates other longer-term dynamics, since the swift speed of scientific progress and the universal character of health issues provide powerful incentives for international cooperation that counteract long-term efforts at denial. This is supported by the theoretical observations of functionalist integration theory, which propounds that technical cooperation tends to increase over time and is able to overcome political limitations on areas of common interest. Henry Chesbrough’s theory of open innovation11 posits that efforts to impose barriers to knowledge-based technologies will fail in settings of pervasive collaboration and quick knowledge spillovers.

In 1965, James Buchanan described club goods as goods between pure public goods, which are open to everyone, and pure private goods, which are both excludable and rivalrous. A club good is excludable but (up to congestion) non‑rival, so members can share it while outsiders are excluded, like a swimming pool reserved for club members. Technology denial regimes work in a similar way - member states share exclusive benefits. Club theory also implies that clubs become unstable if outsiders form their own competing groups, which is what China is now trying to do in semiconductors and AI.

James Buchanan’s economic theory of club goods12 sheds light on the long-term sustainability of technology denial regimes. Technology denial regimes can be described as exclusive clubs that confer benefits to members in the form of excluding non-members. Nevertheless, the sustainability of such clubs relies on their capacity to continue conferring benefits to members, while ensuring the excluded parties do not develop alternative options that minimise the value of club membership.

3. Strategic Effectiveness Framework: The Imposing Country Perspective

For assessing effectiveness of the technology denial regime from the standpoint of the imposing country, it must be quantified in terms of clearly articulated strategic objectives. These are typically things like maintaining technological advantages, deterring opponents from developing capabilities that can be threatening, causing behavioural adjustments, and protecting national security interests. Such goals can be achieved depending on a host of variables that condition the ultimate success of denial.

Supply chain management is, perhaps, the most fundamental driver of regime effectiveness. In the globalised era of today, manufacturing leading-edge technology frequently involves complex transnational supply chains with numerous points of vulnerability and congestion. States controlling key points in these supply chains exercise vast control over the formation of denial regimes. For example, concentration of advanced semiconductor fabrication in a small number of primary facilities worldwide creates natural points of congestion which can be exploited for denial.

However, control of the supply chain is not entirely a question of ownership or capacity to produce; it is also a question of being capable of influencing—or coordinating with—other countries that control complementing segments of the supply chain. This brings us to the central contribution of multilateral cooperation to technology denial regimes. Historical precedent would suggest that unilateral denial efforts are far less productive than concerted multilateral ones. When multiple countries coordinate their export controls and restrictions, they constitute a fuller block difficult to circumvent for target countries.

The scope and specificity of denial attempts also play a critical role in determining their effectiveness. Denial attempts across too broad a range of technologies at once tend to be difficult to implement effectively, and generate strong incentives for the targeted countries to develop independent substitutes. More effective denial attempts can be highly specific, focusing on single critical technologies or capabilities—especially where such technologies are hard to reverse-engineer, or take very long time and significant resources to reproduce independently.

The technological competence and research and development infrastructure of the targeted country is another key element that influences regime effectiveness. Countries with robust indigenous R&D capabilities, ample economic resources, and mature technological ecosystems stand a better chance of surmounting technology denial through indigenous development. This is especially applicable when looking at great technological powers who have the core scientific and engineering competence to copy denied technology, even if such processes take considerable time and investment.

4. Adaptive Measures: The Targeted Country Response Mechanism

Countries under the regime of technology denial are not passive recipients but exercising strategic agents, who form holistic responses to counter or circumvent the impacts of technological restrictions. It is essential to comprehend these adaptive measures in both, evaluating the long-term efficacy of denial regimes and creating stronger implementation strategies.

Indigenous development is the most direct reaction to technology denial, in which national resources are mobilised to make or create indigenous versions of denied technologies. It is most feasible for countries with scientific and engineering expertise, adequate financial resources, and political determination to invest extensively in long-term technological innovation. The effectiveness of indigenous development methods relies significantly on the intricacy of the technology denied, the supply of the expertise, and the horizon of time during which the technology is required.

Nonetheless, indigenous development is not always practical or economical, especially for most technologically advanced and highly complex technologies that take years or decades to develop and require tremendous amounts of financial inputs. In these circumstances, target countries usually try alternative acquisition approaches—such as creating substitute supply chains, co-development with non-participating countries, and attempts at acquiring technologies indirectly.

Another key adaptive measure is the creation of alternative technological blocs. Target countries can aim to create partnerships with other countries that are either not part of the denial regime, or are being denied access similarly. These alliances can enable technology transfer, collaborative development, and the establishment of alternative supply chains that avoid the denial regime’s restrictions.

Circumvention tactics involve a broad array of methods aiming to acquire blocked technologies,in spite of available limitations. These could involve intermediate third-party entities, shell companies, and sophisticated financial structures for concealing final destinations for restricted technologies. Although such tactics might secure short-term access to requisite technologies, they carry meaningful risk and may not ensure secure long-term access.

5. Strategic Impact Analysis: Dual Perspective Matrix Framework

In order to more fully grasp the intricate dynamics of technology denial regimes, we can build analytical frameworks that explore the intersection of several factors impacting both imposing and targeted countries. The initial strategic matrix looks at the connection between supply chain management and multilateral cooperation from the perspective of the imposing country.

5.1. Matrix 1: Imposing Country Strategic Effectiveness Framework

The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) was formed after a major oversight. In 1974, India conducted the ‘Smiling Buddha’ test with plutonium from a Canadian research reactor and heavy water from the US, both intended for peaceful nuclear purposes. This test revealed gaps in safeguards and export controls. In response, major supplier countries formed the NSG to improve these controls.This shows how denial regimes often react to events rather than anticipate them.

| High Multilateral Cooperation | Low Multilateral Cooperation | |

|---|---|---|

| High Supply Chain Control | The Iron Gate For instance: Nuclear technology denial regime Maximum Effectiveness: Complete technological isolation possible, with coordinated international effort creating comprehensive barriers. Long-term strategic advantage likely, with minimal circumvention opportunities for targeted countries. |

The Fragile Bloc For instance: Supercomputing technology denial regime Moderate Effectiveness: Strong control over key technologies, but vulnerable to circumvention through non-participating countries. Success depends on controlling truly critical chokepoints that cannot be easily replicated elsewhere. |

| Low Supply Chain Control | The Paper Wall For instance: The Australia Group’s biotechnology restrictions Limited Effectiveness: Despite international cooperation, fragmented supply chains create numerous circumvention opportunities. Success requires extremely broad participation, and may face significant implementation challenges. |

The Hollow Threat For instance: Restrictions on encryption technologies during the 1990s Minimal Effectiveness: Lacks both the technical means and international support necessary for comprehensive denial. Targeted countries can easily find alternative sources, or develop workarounds. |

Table 1: Imposing Country Strategic Effectiveness Framework

(Source: Author’s Own)

This framework uses the two axes of the extent of Supply Chain Control, and the extent of Multilateral Cooperation, that imposing countries can build. In today’s world of distributed supply chains, it will be very difficult for one imposing country to have control over the entire supply chain required for a technology. In such cases, success or effectiveness of technology denial regimes will depend on how successfully other countries—which have some control over parts of the supply chain—can be brought together for multilateral cooperation. For cases where almost the entire supply chain is under the control of a particular imposing country, multilateral cooperation may not matter a lot. It need not be total control of the entire supply chain; control over large enough parts of the supply chain can also be enough. What is large enough will depend on the context and the objectives.

This table demonstrates that the most successful technology denial regimes involve both, high levels of supply chain control and high levels of multilateral coordination. When imposing powers control key nodes in technology supply chains, and coordinate their actions with other key suppliers, they can establish holistic barriers that it will be hard for the targeted states to breach. Regimes with either a lack of supply chain control or multilateral coordination, however, exhibit major weaknesses in effectiveness.

Let’s look at each quadrant with an example.

High Supply Chain Control + High Multilateral Cooperation: “The Iron Gate”

The nuclear technology denial regime is almost a textbook case for this category. With the NSG (Nuclear Suppliers Group) coordinating among all major suppliers13 and production heavily concentrated, it was able to lock down uranium enrichment and reactor technologies to a remarkable degree, thus building barriers that were extraordinarily hard to get around.

High Supply Chain Control + Low Multilateral Cooperation: “The Fragile Bloc”

US controls on supercomputers to India in the 1990s fit here quite well. American companies largely dominated the supercomputing market, but owing to the fact that these were mostly unilateral restrictions, India eventually managed to build its own systems and cultivate other partners—never really facing a fully global wall.

Low Supply Chain Control + High Multilateral Cooperation: “The Paper Wall”

The Australia Group’s biotechnology controls are a good example of this quadrant. Many of the big biotech suppliers signed on, yet the highly dispersed nature of biotech production and the relative ease of making many biological materials meant that, in practice, even coordinated rules could not produce airtight barriers.14

Low Supply Chain Control + Low Multilateral Cooperation: “The Hollow Threat”

The 1990s push to restrict strong encryption shows what happens in this last quadrant. The US treated robust encryption as a munition under export rules, and tried to cap what could be sent abroad. The effort ran aground nevertheless, as at the end of the day cryptographic schemes are just math that any competent programmer can implement. With no real choke points in the supply chain and limited buy-in from other governments—many of whom disagreed with or ignored these efforts—the result was more posture than actual constraint.

5.2. Matrix 2: Targeted Country Adaptive Response Framework

The second strategic matrix considers the adaptive capability of target countries in terms of their native resources, as well as the availability of alternative alliances.

| High Alternative Partnership Access | Low Alternative Partnership Access | |

|---|---|---|

| High Indigenous R&D Capability | The Resilient Transformer For instance: India’s response to space technology denial Maximum Resilience: Strong ability to overcome denial through combination of indigenous development and alternative partnerships. Can potentially emerge stronger through forced technological independence. |

The Determined Innovator For instance: India’s response to nuclear technology denial Moderate Resilience: Capable of developing alternatives independently but the process may be slower and more expensive. Success depends on time horizon and strategic patience. |

| Low Indigenous R&D Capability | The Dependent Opportunist For instance: Pakistan’s nuclear and missile development programs Limited Resilience: Dependent on alternative partners for technological access, creating new vulnerabilities and dependencies. May achieve short-term access but lacks long-term technological sovereignty. |

The Vulnerable Dependent For instance: North Korea’s attempts to access advanced semiconductor manufacturing technology Minimal Resilience: Highly vulnerable to comprehensive denial regimes with limited options for overcoming restrictions. May be forced to accept technological dependence or abandonment of certain capabilities. |

Table 2: Targeted Country Adaptive Response Framework

(Source: Author’s Own)

The two axes used here are Indigenous R&D Capability and Access to Alternative Partnerships. A country can either use its own R&D capabilities to fight against technology denial regimes, or they can rely on alternative partnerships to circumvent these regimes. The latter will cause them to either develop their capabilities, or acquire technologies denied to them. The success or effectiveness of technology denial depends on these two factors, which make them very interesting axes to use in the study of denial regimes.

This matrix illustrates that countries with robust native R&D capacity and alternative partnerships access are most likely to withstand technology denial regimes. These countries can utilise both their indigenous development efforts, as well as external alliances, to bypass the constraints and potentially become more technologically independent than prior to when the regime of technology denial was enforced.

Let’s look at one example for each of these quadrants.

High Indigenous R&D Capability + High Alternative Partnership Access: “The Resilient Transformer”

India’s handling of space technology denials under the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR)15 is a prime example. ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) leaned on its own launch vehicle development while tapping selective help from Russia and other non-MTCR players, which let it build capabilities that now compete globally on cheap satellite launches.

High Indigenous R&D Capability + Low Alternative Partnership Access: “The Determined Innovator”

Countries in this quadrant grind through slower and pricier paths on their own. After the 1974 nuclear test and NSG setup,16 India fits the bill. Starting with scant alternative partners, it poured decades into mastering the full fuel cycle at home—pulling it off eventually—but with huge costs and delays that outside help could’ve shaved off.

Low Indigenous R&D Capability + High Alternative Partnership Access: “The Dependent Opportunist”

Pakistan’s nuclear and missile technology pathways capture this to some extent. It depended heavily on China and North Korea to skirt Western technology controls. While this did get the job done, it prevented Pakistan from building true indigenous innovation or lasting technology independence.

Low Indigenous R&D Capability + Low Alternative Partnership Access: “The Vulnerable Dependent”

Countries in this situation either stay tech-dependent, or just drop certain ambitions altogether. North Korea’s efforts to acquire advanced semiconductor technology17 closely reflects this scenario. Hit by tightening sanctions in the 2000s and 2010s, it was cut off from cutting-edge chip-making technology and know-how. It also lacked the labs, talent, or ecosystem—unlike China or India—to build it domestically. Today Russia and China mostly stick to UN rules, so North Korea scrapes by with smuggled old chips and basic local production that’s decades behind—hobbling its military, telecom sector, and economy.

5.3. Combined Matrix Analysis

If we pair “The Iron Gate” (imposing country’s side) with “The Determined Innovator” (target country’s side), we get India’s nuclear saga from 1974 to 2008. The NSG controlled the supply chain tightly with almost complete multilateral buy-in, while India had the R&D capabilities but few outside options at first. Yet it still cracked the full fuel cycle after decades of efforts, and denial ended up building its strength. The 2008 India-US Civil Nuclear Agreement basically admitted defeat on that front.

Now let’s consider “The Fragile Monopoly” and “The Resilient Transformer” combination. This fits the US chip curbs on China today. Allies control key chokepoints like ASML’s EUV technology, but cooperation is not very smooth. China is pouring cash into homegrown fabs, data resources and trying to reach side deals with countries like Russia, while also seeking potential cooperation with other countries looking to achieve independence from US-dominated supply chains. So, it will likely hit parity in a decade. China has been, and is, tougher and less reliant; this is like India’s space trajectory, just much faster.

The “Iron Gate” and “Vulnerable Dependent” combination is the case of tech denial working successfully. Iraq in the 1980s, chasing nuclear technology with no real labs or partners, got stonewalled by export controls, intelligence operations and ultimately military intervention. This was a total win for the imposing countries, wherein maximum control by these countries confronted minimal adaptive capacity in the target.

AI technology denial is more “Paper Wall” than “Iron Gate”, since AI development involves algorithms, software, and methodologies rather than only physical manufacturing infrastructure. This keeps supply chain control, when it comes to AI, inherently shaky. China occupies the “Resilient Transformer” quadrant, backed by top-tier research labs and massive compute resources. AI technology denial regime will, therefore, most likely turn out to be even less effective than semiconductor restrictions—closely mirroring how biotechnology controls got undermined by fast innovation, open knowledge flows, and dual-use realities. This will mostly just hasten technological decoupling instead of blocking real progress.

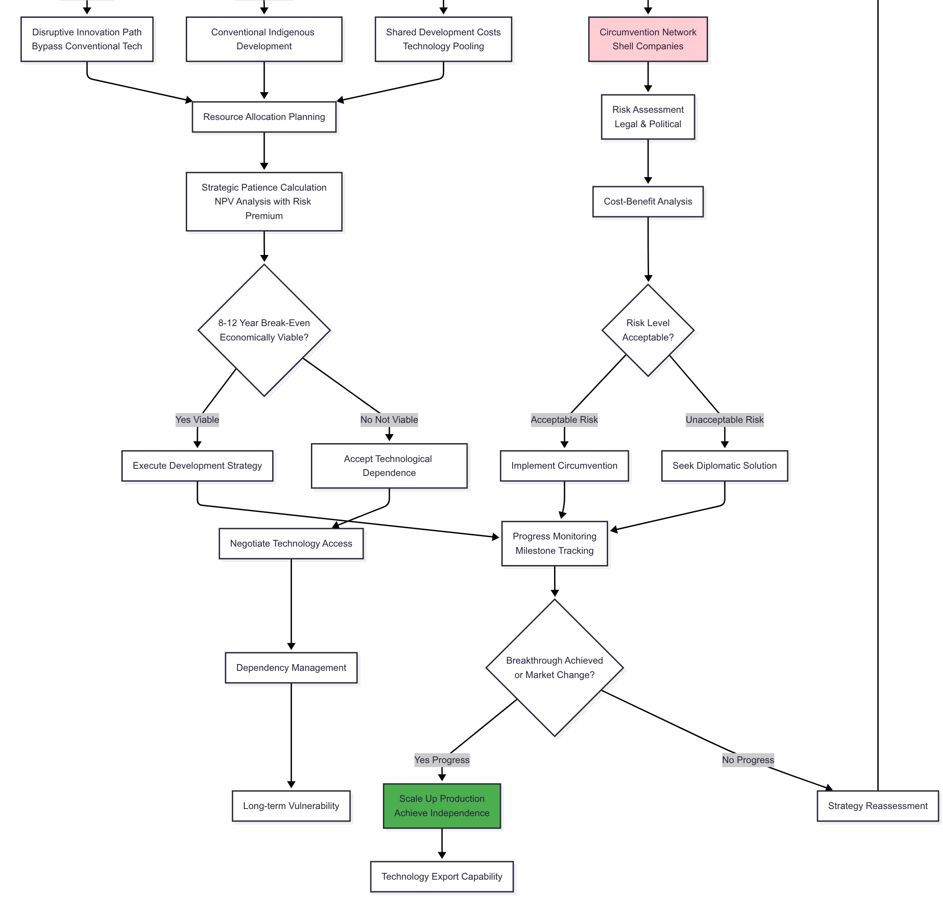

6. Flowcharts

Applying the above frameworks helps come up with flowcharts to aid decision-making for both imposing and targeted countries. Let’s examine what these flowcharts would look like.

6.1. Imposing Country Flowchart

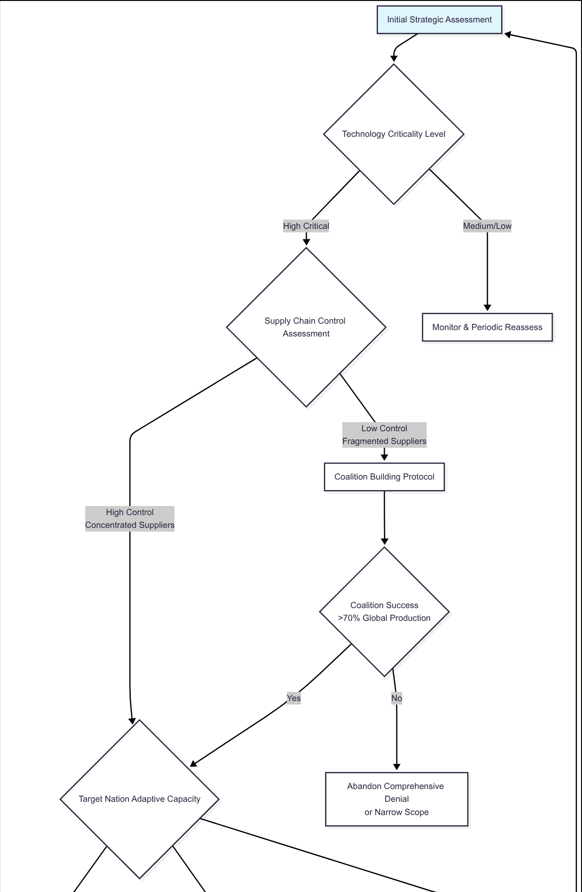

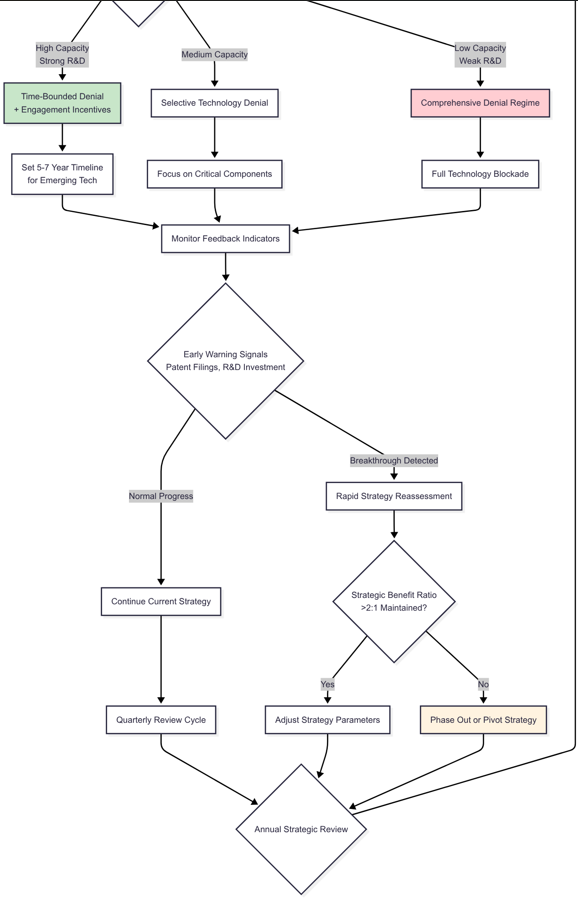

The flowchart discussed in this section presents the strategy that an imposing country should follow for successful implementation. The flowchart can be found here. (For purposes of image clarity, the flowchart primarily has been hosted at the above provided link while the same image—split into two halves—is reproduced here.)

Figure 1a: Imposing Country Flowchart - Part 1

(Source: Author’s Own)

Figure 1b: Imposing Country Flowchart - Part 2 - in continuation of Figure 1a. (The combined Figure is presented below in Figure 1c, which can also be accessed at the link provided above.)

(Source: Author’s Own)

Figure 1c: Imposing Country Flowchart

(Source: Author’s Own)

The dominant country flowchart is a dynamic three-dimensional measurement system that weighs technological criticality, supply chain mastery, and target country adaptation. This can be used to analyse how imposing countries have generally gone about with technology denial implementation. It can also be used by targeted countries to make an assessment about the eventual efficacy of technology denials.The model recommends setting a critical bar of needing some threshold of world production capacity under multilateral command, before acting to undertake total denial efforts. This bar could be different in different contexts, and should be devised based on some empirical data. For illustrative purposes, the model assumes a 70% threshold.

Its most important aspect is the feedback loop mechanism integrating early warning signals like patent filing trends, R&D expenditure patterns, and changes in international collaboration. When targets have high adaptive potential, reflecting a strong indigenous R&D base—like that of India’s space program—the flowchart diverts from open-ended denial to time-limited limitations of 5-7 years for emerging technologies. This temporal nuance overcomes the rigidness of conventional policy frameworks that get outdated with technology change.

Risk evaluation procedures should analyse possible blowback consequences by employing game theory simulation of reprisal situations. Comprehensive denial regimens would only work when there are greater-than-2:1 benefit ratios of positive strategic results. Quarterly and yearly review cycles would provide ongoing recalibration against shifting technologies and geopolitics, thereby avoiding the policy inflexibility that hollowed out so many technology control attempts in the past.

The flowchart begins with an initial strategic assessment of the criticality of the technology. This criticality would vary according to context. Technology denial regimes are needed for highly critical technologies; for other technologies, periodic reassessment is recommended to assess if the situation has changed. For highly critical technologies, the next step is to assess the extent of supply chain control that the imposing country exerts. For technologies in which the imposing state has low level of control and there are fragmented suppliers, coalition building becomes important, as only when there is a critical mass of countries in this coalition will technology denial regimes have a chance of working. The flowchart assumes a 70% threshold for illustrative purposes, but ideally this number should be arrived at empirically. For a highly concentrated supply chain, the next step is to assess the target country’s adaptive capacity. For target countries that have high R&D capabilities, the denial regime should be time-bound and offer some engagement incentives to encourage cooperation. These timelines help reassess the strategy periodically. For target countries with medium capabilities, the denial has to be selective and focussed on just the very critical components. This is because these countries can develop capabilities, and the imposing country would want to focus efforts on the most critical part. For countries with low R&D capacities, a comprehensive denial regime is recommended.

The next step is to keep monitoring the feedback indicators from targeted countries for early warning signals like patent filing trends, R&D expenditure patterns, and changes in international collaboration. For target countries which show just normal progress, the same denial regime can continue. But for countries that show some breakthroughs, there has to be a rapid strategy reassessment to ascertain if the cost-benefit analysis still works out in favour of the denial regime. If the cost-benefit analysis is still favourable to the imposing country, then only some parameters can be tweaked. If this is not the case, then either the regime should be phased out or there has to be a major pivot to another strategy. And finally, all of this needs to be reviewed periodically.

Let’s try and apply this flowchart against the denial regimes of nuclear technology and semiconductors as two illustrative examples of the way in which imposing states have utilised—or strayed from—the strategic trajectory of the flowchart.

In the nuclear technology denial regime, the recommended order of the flowchart—evaluation of technological criticality, mastery of supply chains, and the adaptive capacity of the target—were generally applied. The NSG determined nuclear technology as a highly critical technology,18 and attempted to concentrate supply chain mastery under a closely integrated set of suppliers. This multilateral alignment met the flowchart’s second requirement: surpassing more than 70% global capacity control prior to implementation. Through coordination of restrictions on reactor technologies and nuclear materials, the NSG established a near-monopoly on critical inputs. Where the regime went awry, however, was its inability to maintain adaptive feedback and temporal flexibility. The flowchart suggests a feedback loop to rebalance controls in accordance with signs such as indigenous R&D expansion, or new alliances. The NSG’s inflexibility enabled India to go ahead autonomously, building end-to-end fuel-cycle capacities and taking advantage of limited cooperation from non-members. A more dynamic use—such as an occasional review of India’s adaptation path and graduated engagement, rather than complete isolation—may have maintained strategic leverage and prevented the final loss of regime effectiveness.

Conversely, the China denial regime for semiconductors follows the flowchart’s early logic, but is hampered by its prescriptions over the long term. The US and its allies properly recognised semiconductors as an enabling, highly critical technology and coordinated export controls in multilateral fora with Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea—thus surpassing the flowchart’s coordination threshold. The flowchart also recommends initial risk assessment of blowback, and a flexible horizon of 5-7 years for fast-changing industries—something the American strategy has partially neglected. Though the early actions were tactically successful in inhibiting access to extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography equipment,19 the dynamic aspect of the flowchart—planning ahead for target adaptation—has yet to be maximally utilised. China’s huge R&D expenditures, talent poaching, and alliances with allies reflect the kind of adaptive resiliency the flowchart cautions against overlooking. Rather than carrying on the suggested quarterly and annual adjustment cycles, the dominant alliance has for the most part embraced static, unidirectional prohibitions. This invites the same “strategic reversal” one observes in India’s nuclear scenario, where denial ultimately fueled indigenous innovation and alternative supply chains.

Had the big powers implemented the adaptive loop of the flowchart more strictly—varying phased involvement, reviews of technology life-cycles, and mechanisms for proportionate relaxation—the regimes might have been able to sustain coercive leverage, while avoiding long-term fragmentation.

China’s efforts to deny technology to Japan and the US provide a clear example that supports several points in the flowchart, and shows some extra challenges. By limiting exports of rare earth elements and key minerals like gallium and germanium,20 China demonstrated what can happen when a country controls much of the supply chain—holding 60-80% of global production21—but does not enjoy wide international support. This is an example of a “Fragile Monopoly.” The flowchart suggests that this kind of strategy will work to some extent but is easy to get around, which is what happened eventually. In response, Japan and the US found new suppliers, invested in their own processing, and built partnerships with countries like Australia and those in Africa. Since China did not work with other potential suppliers, the targeted countries could use the diversification strategies described in the Targeted Country Framework. If China had teamed up with other rare earth producers, or followed the flowchart’s advice to slowly increase restrictions and watch for signs of adaptation, it might have kept its advantage for a longer time.

The rare earth case also elucidates an important point that the flowchart only suggests, which is that there is a difference between having resources and having the technology to process them. China’s real strength comes more from its processing skills and willingness to accept the environmental costs, than from owning rare earth deposits. Owing to this—in this context—the flowchart’s idea of “supply chain control” should include both access to raw materials and the ability to process them, since having only one is not enough for lasting power. When China limited rare earth exports to Japan in 2010,22 Japan’s strong R&D helped it develop recycling methods and alternative materials, thus reducing its dependence in just five years. The flowchart’s feedback loop mattered here, since China’s strict and unchanging restrictions actually sped up Japan’s move toward independence. This supports the flowchart’s advice to review strategies regularly and adjust timing, showing that even a strong supply chain position can weaken if the strategy does not change in response to the target country or new technology.

These cases together illustrate that although the Imposing Country Flowchart offers a sound conceptual map—grounded in criticality appraisal, multilateral control, and feedback loops—the key to its success lies in continued flexibility and prompt recalibration.

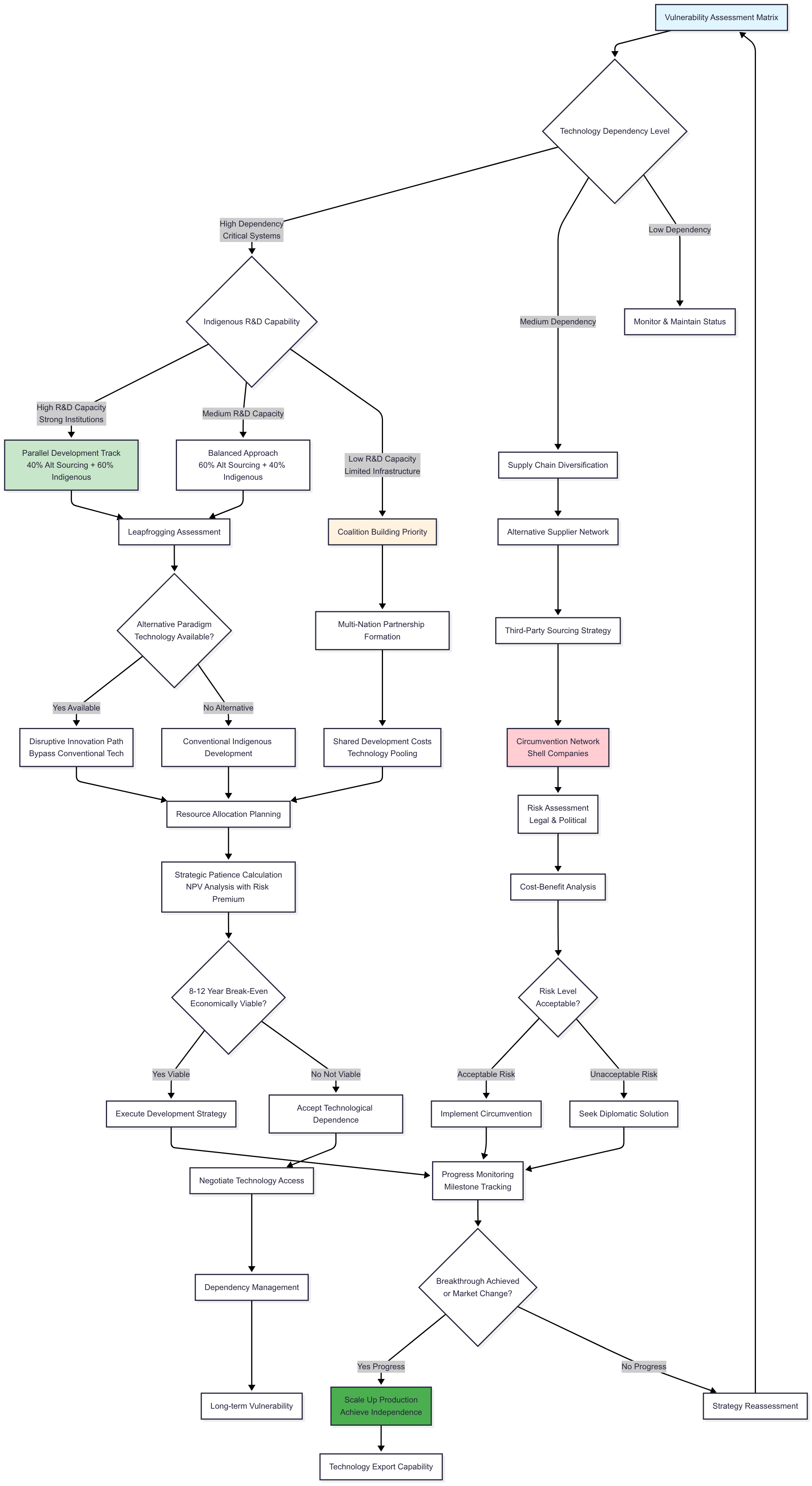

6.2. Targeted Country Flowchart

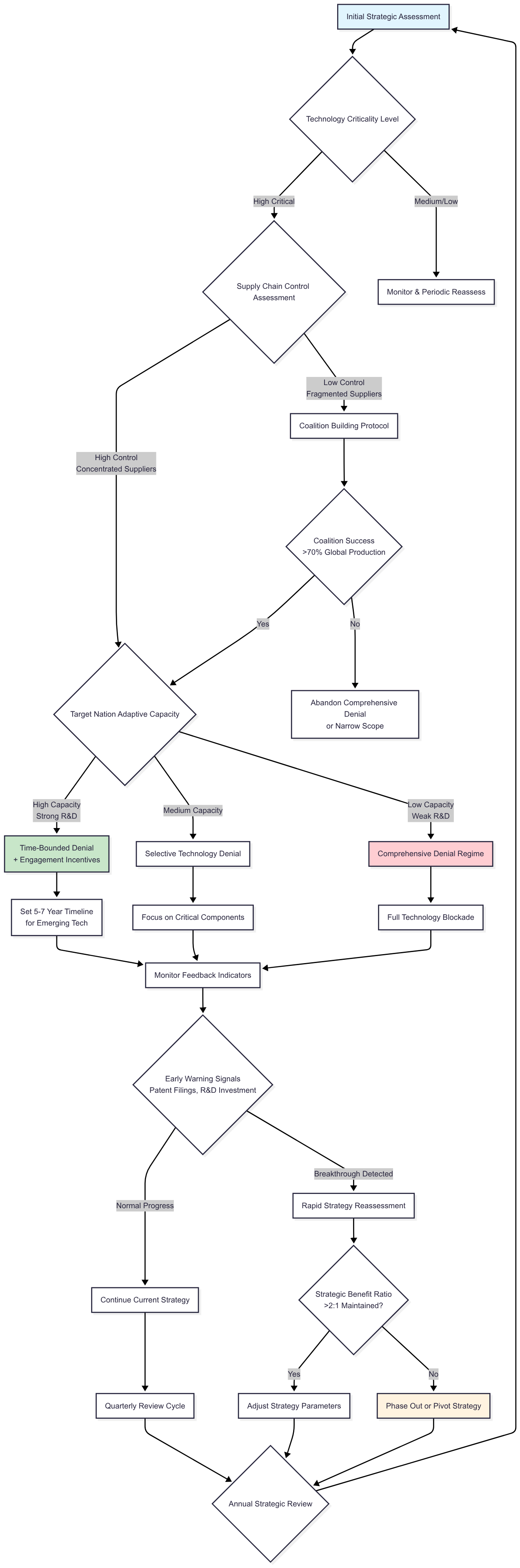

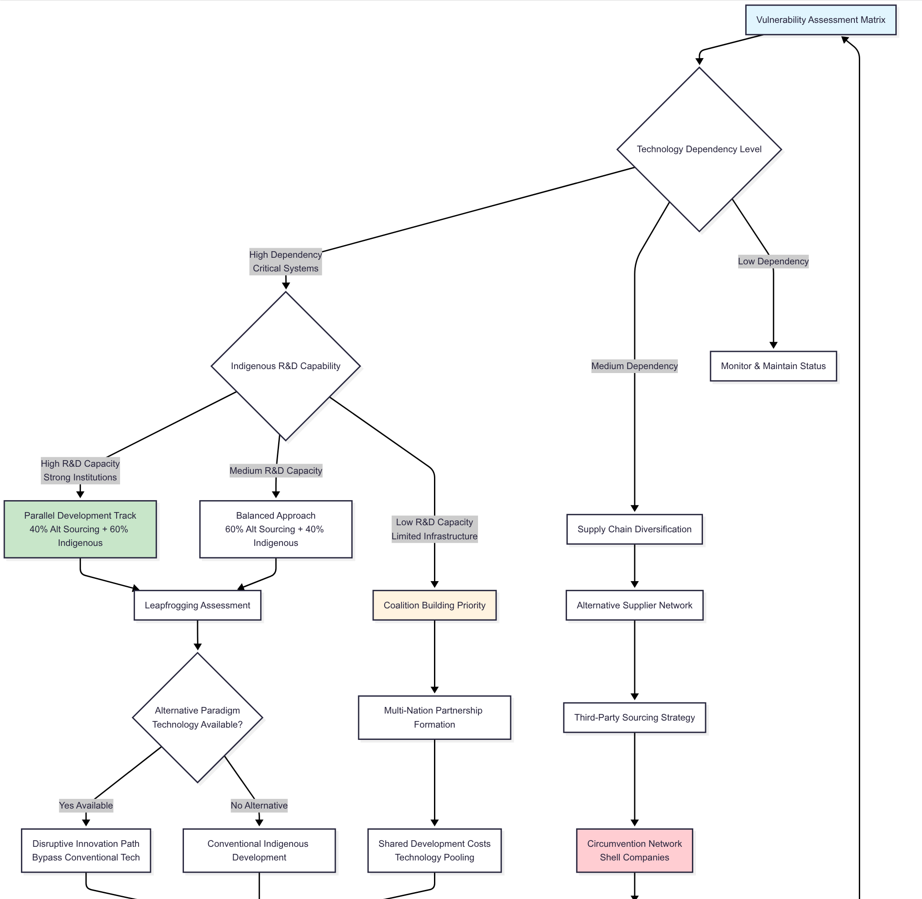

The flowchart discussed in this section presents the strategy that an imposing country should follow for successfully navigating technology denial regimes. The flowchart can be found here. (For purposes of image clarity, the flowchart primarily has been hosted at the above provided link while the same image—split into two halves—is reproduced here.)

Figure 2a: Targeted Country Flowchart - Part 1

(Source: Author’s Own)

Figure 2b: Targeted Country Flowchart - Part 2 - in continuation of Figure 2a. (The combined Figure is presented below in Figure 2c, which can also be accessed at the link provided above.)

(Source: Author’s Own)

Figure 2c: Targeted Country Flowchart (Source: Author’s Own)

Targeted states should focus on vulnerability mapping and strategic autonomy creation through careful analysis of technological substitutability, supply chain diversification possibility, and local capability shortfall. Countries with high dependence, along with high R&D capability, fall into a parallel development path—investing 60% funds in indigenous development and 40% in alternative sourcing. Again, these numbers are suggestive; the actual numbers could vary according to context and therefore, should be reached based on empirical data and analysis.

Clayton Christensen argued that established companies often fail not because they are incompetent, but because they focus on their best customers. This leaves the lower end of the market open to new, simpler, and cheaper competitors who can eventually improve and overtake them. In technology denial, forcing a country to make its own substitutes can sometimes help it catch up or even surpass the original technology. For example, India’s affordable satellite launches began to compete with established providers.

The system adapts Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation model by leapfrogging assessment regimes via novel technological paradigms. In cases where traditional technology access is withheld, the system gives priority to radically different solutions that could gain equivalent capabilities. An example here is that of India creating affordable space launch vehicles that eventually competed with traditional high-cost alternatives, using innovative reusable technologies and modular design methods.

Strategic patience estimates use net present value analysis—incorporating geopolitical risk premiums, tech sovereignty gains, and possible export market possibilities. This flowchart has chosen a break-even value of 8-12 years for illustrative purposes, in order to understand viability of the strategy in terms of reaching competitive export advantage (the actual value will vary based on context and has to be arrived at empirically). For unviable strategies, this has to lead to an acceptance of technology dependence and negotiation of technology access to navigate dependency management. This, however, leads to long term vulnerability.

Leapfrogging in development economics means that newcomers can skip older technologies and go straight to the latest ones. This is seen in mobile banking in sub-Saharan Africa, where people skipped landlines and desktop computers. In technology denial, this can backfire. Blocking access may push a country to invest in newer technologies instead of copying current ones, which could leave the original country stuck with outdated standards.

For target countries with low R&D capacity, coalition-building becomes very important so that development costs can be shared. Coalition building corridors turn on when several countries experience similar constraints, which allows cooperative development to distribute costs and expedite capability acquisition.

For technologies which are not high on the vulnerability ranking for the target countries, a strategy of supply chain diversification can be followed with accompanying cost-benefit analysis and risk assessment. If the risk is acceptable, the same strategy can be continued, otherwise some diplomatic solution has to be negotiated. In all cases, regular progress monitoring needs to be done to check if either the market has changed or a breakthrough has been achieved in the relevant technologies, which could transform the whole situation. If that is the case, then the path moves towards scaling up production, achieving independence and gaining technology export capability. In all of these instances, periodic strategy reassessments are essential to adapt strategies to changing realities.

Using this flowchart to analyse the Indian experience of denial of space technology illustrates how well the framework can inform adaptive strategy. When the MTCR cut off India’s access to key space launch and propulsion technologies, the ISRO took a course of action consistent with the logic of the flowchart. The initial step, vulnerability mapping, charted high reliance on foreign guidance and launch systems. The second stage, resource allocation, followed approximately the flowchart’s suggestion of spending about 60% on local R&D and 40% on alternate sourcing. ISRO invested national resources in bringing up local launch vehicles such as PSLV and GSLV,23 and maintaining limited cooperation with non-MTCR countries like Russia.

The emphasis on parallel development and long-term strategic patience in the framework is relevant here, since ISRO attained virtual autonomy in two decades. There were, of course, some divergences which bolster the flowchart’s main thrust: the flowchart-dictated coalition-building among similarly constrained countries remained underexploited. India’s reply was substantially self-reliant in nature—rather than collaborative—which, although successful, postponed results and raised costs. Nevertheless, the case confirms the flowchart’s predictive power—demonstrating that high indigenous R&D capability and selective partnerships can turn imposed vulnerability into long-term strategic advantage.

7. Policy Prescriptions

Based on this thorough analysis across multiple industries, and drawing on wide-ranging theoretical constructs, a number of prescriptions arise for countries contemplating the adoption of technology denial regimes. The historical evidence from nuclear, biotech, space, defence, and computing industries indicates that the regimes are likely to be most effective when they target identified critical technologies, instead of trying broad-based controls. Targeted methods are simpler to apply, enforce, and maintain over time, as evidenced by the relative success of nuclear technology controls over the more limited potency of sweeping biotechnology, or dual-use technology prohibitions.

Theoretical knowledge from collective action theory, supplemented by empirical knowledge from cases such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group and the Australia Group, makes the conclusion highly probable that multilateral cooperation is a prerequisite for successful technology denial. Unilateral action is much less likely to be effective, and could subject the implementing country to disproportionate costs. Constructing a wide range of international agreements involves subtle diplomacy, and usually entails trade-offs and bargains that might constrain the extent of denial action. Yet, the track record of nuclear non-proliferation suggests that persistent multilateral action can attain important strategic goals over many years.

An examination of India’s adaptive measures across various sectors indicates that target countries must be given careful consideration of their adaptive capacity when devising denial regimes. Countries possessing robust native research and development bases, such as India, can potentially break through over time and emerge more technologically independent. The theoretical approach of endogenous growth theory indicates that countries with good human capital and institutional abilities will eventually come up with the technologies they think are important for their development and security, regardless of any external limitations.

In such instances, denial regimes might have to be accompanied by positive incentives and engagement policies in order to succeed in the long run. The history of nuclear commerce restrictions moving towards India and leading to the 2008 Civil Nuclear Agreement, demonstrates how acknowledging developing capabilities and changing strategic relations can result in more successful strategies that integrate elements of cooperation and competition.

Effective use of technology denial as a bargaining tool in international negotiations demands strategic dexterity. Denial regimes are often more successful when embedded within a broader menu of incentives—offering the prospect of technology access in exchange for policy concessions, security guarantees, or economic cooperation. When coupled with positive inducements such as financial rewards, preferential terms of trade, or collaborative R&D initiatives, the likelihood of changing the targeted country’s behaviour increases.

Technology denial, therefore, is rarely an end in itself. It must be orchestrated in concert with other levers—diplomatic, financial, and strategic—to reinforce the intended outcome and maintain flexibility for future engagement.

The political and economic viability of denial regimes demands sensitivity towards domestic constituencies and international allies. Both benefits and costs of such regimes must be clearly articulated, and provisions for regular review and adaptation must be incorporated into their execution. The public choice theory offers the theoretical prediction that concentrated interests impacted by technology controls will organise to shape policy, and viable regimes need to factor in such political processes.

For the targeted countries, this study recommends a number of strategic maxims to counter technology denial regimes. To begin with, indigenous research and development investments form the best defence against long-term denial activity. Although these types of investments take a long time and are costly, they represent the most assured route towards technological self-reliance. India’s experience in various fields makes it clear that countries with robust scientific and educational infrastructures can produce competitive indigenous substitutes to restricted technologies, but the effort demands considerable resources and dedication over the long term.

Theoretical premise of innovation systems theory is that indigenous development must go beyond research and development investments; it must have innovative ecosystems that comprise educational institutions, research institutions, industrial capabilities, and supportive policy frameworks. The success of India in the development of homegrown capabilities in a range of restricted fields, indicates the robustness of its overall innovation system. It reinforces that the targeted countries must aim to develop complete technological capabilities, instead of seeking narrow technological fixes.

Second, diversification of supply chains and sources of technology can minimise exposure to denial regimes. Establishing relationships with several sources and creating alternate channels for securing technology, enhances immunity to denial by any one source. India’s approach to building alliances with countries not within dominant technology denial regimes—like Russia during the Cold War—demonstrates how specific countries can take advantage of shortcomings in multilateral coordination to continue accessing key technologies.

Third, international alliances and coalitions can offer both alternative sources of technology and bargaining power collectively in countering denial regimes. Together, it may be more successful than any one country acting alone. The theoretical underpinnings from alliance theory indicate that countries confronted by similar external constraints are poised for high incentives when allying themselves with one another, as doing so will generate alternative centres of power that can counter current technology control regimes.

The analysis further implies that target countries need to develop long-term strategic visions in reacting to regimes of technology denial. Disruptions and short-term expenditures must be balanced against long-term gains of technological autonomy, and decreased reliance upon potentially untrustworthy suppliers. India’s readiness to incur significant short-term expenditures in creating indigenous nuclear, space, and defence capabilities eventually made the country a more autonomous and powerful player in international technology markets.

Fourth, targeted countries must aim to build capability in emerging and prospective technologies, instead of attempting to merely copy current proscribed technologies. Technological leapfrogging theory predicts that excluded countries can possibly create better alternative solutions when they cannot follow established technological paths. India’s creation of innovative solutions in fields such as digital identification, mobile transactions, and frugal engineering shows how limitations may fuel invention that ultimately yields competitiveness.

This also brings us to the very important role played by asymmetric capabilities in the success or failure of technology denial regimes. Unconventional methods and tactics provide the element of surprise that can prove to be the differentiating factor for both imposing and targeted countries. The next section looks at some such asymmetric options.

7.1 Asymmetric Capabilities in Technology Denial Regimes

7.1.1 Information Warfare and Cognitive Domain Operations

Conventional technology denial regimes tend to concentrate on physical and regulatory obstacles, without addressing the full potential of information-based asymmetric measures. Information warfare potential provides advanced countries highly effective technology denial tools that function beneath standard policy ceilings, but may be more effective. Such methods take advantage of inter-connectedness among cutting-edge technology environments, where information transmission tends to be more vital than material components.

Cyber-enabled supply chain monitoring is one aspect of asymmetric information operations. Instead of depending on export licensing and customs enforcement, technologically advanced countries can utilise persistent monitoring systems that monitor technology components across global supply chains. These systems are capable of detecting attempts at circumvention, tracing alternative sourcing networks, and providing real-time intelligence on target country’s acquisition strategies. The 2020 SolarWinds attack24 showed how advanced actors can insert surveillance capability into technology supply chains, although such methods could (in theory) be used to enable denial enforcement instead of espionage.

Standard-setting leverage is yet another asymmetrical instrument frequently underestimated in traditional analysis. States with significant membership in international standards-making bodies can insert requirements beneficial to their technologies at the expense of the competition. This method is especially effective for nascent technologies when standards are still in flux. Chinese standard-setting leverage in 5G—through bodies such as 3GPP25—shows how early entry into standard setting can generate durable competitive advantages that operate as de facto technology denial barriers against late movers.

Disinformation operations against technology adoption are a more contentious, but possibly potent, asymmetric strategy. By collapsing competitor technologies’ credibility through coordinated information operations, imposing powers can realise market-based denial effects without formal limits. The international 5G security concern debate illustrates how information campaigns can dictate technology adoption choices, regardless of technical merit evaluation.

7.1.2. Economic Asymmetric Strategies and Market-Based Denial

SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, is a Belgian cooperative that sends payment messages between banks. Almost all major international transactions use it, so being excluded can cause serious financial harm. Russia’s partial removal in 2022 was not the first time SWIFT was used this way. When Iran was disconnected in 2012, it quickly lost much of its oil revenue. These actions have led to more global efforts to build alternative payment systems, which is the kind of strategic shift discussed here.

Access to the financial system is one of the most potent asymmetric weapons in the toolkit of leading economic powers that can work through market forces, and not direct regulatory intervention. The cutting off of Russian banks from SWIFT networks, after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine,26 showed how control of financial infrastructure can deny technological access by disconnecting payment and financing mechanisms. This strategy is most effective as it utilises network effects that are a function of international financial systems.

Targeted investment limitations present a further asymmetric aspect that was not given much emphasis in the initial investigation. Instead of just export control, recipient countries can limit foreign investment in key technology sectors, exclude access to capital markets, or inhibit takeover of technology firms. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)27 demonstrates how investment screening can act as technology denial by keeping foreign players out of domestic capabilities or proprietary technologies through forms of ownership.

The CFIUS was set up in 1975 but was mostly inactive until the 1980s, when Japanese purchases of American companies raised political worries. The 2018 Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) made CFIUS much stronger by letting it review minority stakes and joint ventures, not just full takeovers. CFIUS is especially powerful because it works in secret: reviews are confidential, decisions are rarely explained, and the President can formally block covered transactions on national security grounds. This makes it one of the most quietly effective technology denial tools in the US.

Currency and trade finance manipulation are other asymmetric means by which technology denial goals can be indirectly attained. By limiting the availability of prevailing currencies required for cross-border technology transactions, or withholding trade financing for targeted industries, exporting countries can establish de facto barriers in the absence of explicit export restrictions. The method takes advantage of the structural benefits associated with reserve currency status and prevailing financial institutions.

Market fragmentation strategies are a less overt asymmetric strategy that emphasises the establishment of incompatible technology ecosystems instead of outright denial. Through the advancement of proprietary standards, restrictive licensing deals, and closed development platforms, dominant technology players are able to exclude rivals while leaving room for deniability of protectionist motives. Apple’s iOS ecosystem is a good example of how closed platforms can exercise control through incompatibility instead of prohibition.

7.1.3 Human Capital and Knowledge-Based Asymmetric Operations

Talent attraction and brain drain tactics are probably the least developed asymmetric aspect of technology denial practices. Instead of emphasising technology transfer controls, countries can realise comparable goals by systematically targeting the most important researchers and engineers from rival countries. The past success of the US in recruiting international talent through initiatives such as the H-1B visas, is an example of how human capital initiatives can create long-term competitive edge in strategic technologies.

Reverse brain drain actions by specific countries provide symmetrically opposing counter-strategies. They include countries such as China and India, which have launched high-level talent return schemes offering economic rewards, research facilities, and career development opportunities to bring their diaspora engineers and scientists back from Western academies. Such schemes can gain access to advanced knowledge and know-how that official technology transfer limitations cannot bar.

Educational and research collaboration limitations are another asymmetric instrument that affects the recipient country through knowledge diffusion, as opposed to technology transfer. By restricting faculty exchanges, collaborative research projects, and university alliances, imposed countries can delay knowledge diffusion to rival countries. Nevertheless, this measure is fraught with the high risk of setting national institutions outside the international knowledge network, thereby weakening long-term innovation potential.

Industrial spying and collection of technology intelligence, though legally questionable, are asymmetric capabilities used by some countries to evade official technology denial regimes. Restricted countries may turn to clandestine acquisition techniques that skirt conventional export controls and licensing measures. The widespread reporting of state-backed industrial spying operations would imply that official denial regimes accidentally encourage illicit acquisition techniques.

7.1.4. Technological Paradigm Disruption and Alternative Development Paths

The most advanced asymmetric approach is to actively seek out alternative technological paradigms that sidestep embargoed technologies altogether. Instead of trying to imitate denied capabilities, target states may invest in essentially dissimilar means that accomplish comparable results through distinct paths. This approach turns technology denial from a limitation into an innovation driver.

Distributed and decentralised alternatives are one such paradigm shift opportunity. If access to the high-performance computing systems of a central system is limited, the targeted countries may invest in distributed computing architectures that combine many smaller systems to provide similar capabilities. Blockchain technologies illustrate the way in which distributed solutions can at times provide better security and resilience features than centralised alternatives.

Software-based solutions provide yet another asymmetric development avenue when hardware access is limited. As more and more technologies become software-defined, opportunities are presented for countries that have robust programming capability to gain hardware-equivalent functionality through complex software implementations. Software-defined radio technologies28 provide examples of how the sophistication of software can make up for hardware deficiencies in communication systems.

Biological and quantum computing are nascent paradigms that have the potential to fundamentally upset traditional approaches to technology denial. Countries that invest early in these alternative computing paradigms may literally bypass conventional semiconductor-based limitations altogether. Though these technologies exist in an experimental form at this stage, their paradigm-disrupting potential makes them a desirable asymmetric investment opportunity for countries experiencing traditional technology constraints.

The asymmetrical aspect of technology denial regimes exposes how conventional policy structures tend to ignore the most innovative and potentially potent options available to both imposing and targeted countries. Technology competition success is increasingly a function of being able to think outside the box and utilise nontraditional assets that adversaries will not expect, or be able to counter adequately.

8. Predictions for the US-China Technology Denial War in AI and Semiconductors

Drawing on the theoretical foundations and historical trends presented in this paper, the US-China AI and semiconductor technology denial regime will take a course significantly different from that of earlier nuclear or space technology controls. It will come with several important differences that will fundamentally determine its success and endurance.

Comparing the US strategy with the Strategic Effectiveness Framework, the semiconductor denial regime at first seems to be located in the “Maximum Effectiveness” quadrant—merging strong supply chain dominance with high multilateral coordination. The centralisation of top-of-the-line semiconductor fabrication equipment in entities such as ASML29—supported by concerted restrictions from allies such as the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea30—constitutes integrated impediments that China cannot readily bypass in the short term. But this seeming strength conceals severe vulnerabilities that will intensify with time.

The semiconductor example is qualitatively different from successful precedents in history such as nuclear technology denial because semiconductors are an enabling technology, and not an end-use military capability. Semiconductors are unlike uranium enrichment, which has a very restricted set of civilian uses, being central to almost all areas of contemporary economic activity. This dual-purpose ubiquity imposes an enormous economic burden on the denial regime, which will grow as international supply chains fragment and become more expensive. Weaponised interdependence theory predicts that while the US can use its structural leverage in semiconductor supply chains to procure short-term strategic benefit, doing so will drive the development of alternative networks that will eventually circumvent US control altogether.

China’s location in the Targeted Country Adaptive Response Framework puts it squarely in the “Maximum Resilience” quadrant, with high indigenous R&D capability31 and high access to alternative partnerships. In contrast to India’s history of nuclear technology denial—where there were few alternative suppliers—China can take advantage of its relationship with Russia, which has high semiconductor design capabilities if not high manufacturing capabilities. China can also potentially collaborate with nascent suppliers in countries unencumbered by US restrictions. More importantly, China’s huge domestic market offers natural demand-side backing for local semiconductor development which was missing in the majority of previous technology denial cases.

The public release of Meta’s LLaMA model weights in 2023 made it much harder to control the spread of AI technology. Once these model weights are available, they cannot be taken back. They spread quickly online and can be adapted using basic hardware. This situation is different from nuclear or semiconductor controls because a single decision by a private American company can quickly undermine a government’s denial strategy. It shows that efforts to restrict AI technology are especially vulnerable to actions within the country trying to impose the controls, a challenge that current policies have not yet addressed.

The AI element of the denial regime meets even more fundamental hurdles, based on the theoretical observations from biotechnology and software instances investigated in the paper. AI technologies are largely software, algorithms, and methodologies. They aren’t physical devices, and thus inherently less easy to control by traditional export restraints. The accelerated speed of AI creation, coupled with the open-source character of some of the underlying AI technology, generates what this document refers to as a “democratisation of innovation” phenomenon that will methodically erode restrictive controls over time.

Forecasting the medium-term direction, the regime of semiconductor denial will probably attain tremendous tactical gains for about 3-5 years, throughout which China will suffer enormous limitations in building advanced chip fabricating capabilities. At the same time, this will catalyse China’s domestic development into responses that will emulate India’s reaction to space technology denial. The enormous resource mobilisation already in progress in China’s semiconductor industry—together with talent recruitment programs and other partnership formation alternatives—implies that by 2030 China will have domestic capabilities that, though at first inferior to cutting-edge Western technology, will be adequate for the majority of civilian and most military uses.

The longer-term strategic effects become more troubling for the position the US is in,when considered within the context of technological paradigm disruption theory outlined in the document. The exclusion of China from Western semiconductor supply chains is stimulating investment in alternative computing paradigms such as neuromorphic computing, photonic processors, and quantum computing architectures. The alternative methods might avoid traditional silicon-based restrictions altogether, producing what this document calls “strategic reversal” whereby denial actually makes the competitive position of the targeted country stronger.

The AI denial component will be much less effective than semiconductor restrictions. The globalised nature of AI research, the ease with which knowledge is transferred through academic and commercial networks, and the quick pace of algorithmic innovation will provide several opportunities to circumvent. China’s great domestic AI research capacity, and the ability to access substitute data streams and computing power, leave it well placed to continue competitive AI development in defiance of Western embargoes.

The US-China technology contest is not one-sided. China has started to use its own technology denial strategies, similar to those discussed in this paper. At the beginning of this decade, China restricted exports of gallium and germanium to the US and its allies.32 This move fits the “Fragile Monopoly” model, as China produces about 60% of the world’s gallium and 80% of its germanium,33 but does not have full support from other countries. These materials are essential for making semiconductors, military equipment, and renewable energy technologies, giving China influence over supply chains that Western countries had previously relied on. This example shows that a country targeted in one area can also be the one imposing restrictions in another, taking advantage of weaknesses in its rivals’ supply chains. China’s approach matches the theory of weaponised interdependence—using its strong position in rare earths and critical minerals to put pressure on countries that try to limit its access to advanced semiconductors. This creates a situation where both sides are vulnerable, which was not the case in earlier examples like nuclear technology denial.

China’s export restrictions on Japan, such as the 2010 rare earth embargo after the Senkaku Islands dispute and more recent limits on processing technology, show how even partial control of a supply chain can provide strategic power—especially when combined with geographic concentration and technical know-how. In response, Japan spent the next decade working to find new sources of rare earths and develop recycling methods. This effort matches the adaptive strategies described in our Targeted Country Framework, as Japan invested in its own capabilities and built new partnerships with Australia, Vietnam, and India.34 This example highlights a key difference between today’s technology denial and what happened during the Cold War: now, control over supply chains is spread across many areas, so most major economies are both imposing and targeted countries depending on the technology. This mutual denial makes the strategic environment more complicated, so traditional one-way denial models need to be updated with game-theory approaches that consider competition across several technological areas—each with its own supply chain and coordination challenges.

Geopolitically, the semiconductor and AI denial regime will hasten the development of alternative technology blocs, as complex interdependence theory foresees. Instead of perpetuating Western technological pre-eminence, these limitations are encouraging the development of a China-led technology ecosystem with Russia—and possibly Iran—along with other countries either cut out of or opting out of US-dominated value chains. This fragmentation will in the end weaken Western technological leverage, as the international technology marketplace becomes irreversibly bifurcated.

The economic viability of the denial regime confronts internal contradictions that will become more intense over time. Western semiconductor firms are already suffering substantial revenue loss35 from limited Chinese market access, which generates domestic political pressure for relaxing controls. Public choice economics theory implies that those concentrated industry interests will ultimately prevail over more dispersed national security interests, especially as the strategic advantages of denial grow less evident and the economic costs more evident.

Most importantly, this paper’s examination of the life-cycle theory of technology implies that the present effort to limit access to leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing could ultimately be strategically self-defeating. As semiconductor technology ages and production abilities spread across the globe, today’s chokepoints will increasingly become less consequential. In the meanwhile, the denial regime is unwittingly stepping up China’s development of next-generation computing technologies that may bypass present-day semiconductor constraints altogether.

The final forecast, drawn from past trends and theoretical models presented in the document, is that the US-China technology denial regime will evolve on the trajectory of nuclear technology restrictions on India but will accelerate in time owing to the more rapid advancement of technology. Initial tactical triumph will be replaced by strategic adaptation by China, eventually leading to an increasingly technologically independent and competitive rival in a decade. The regime’s most lasting impact will not be the prevention of Chinese technological advancement, but rather the permanent fragmentation of global technology markets and the acceleration of alternative technological development paths that may ultimately disadvantage the very countries that initiated the restrictions.

9. Conclusion

Technology denial regimes are a sophisticated and dynamic instrument of modern statecraft that may be effective under certain circumstances but pose considerable constraints and challenges—as illustrated through in-depth examination of nuclear, space, and computing fields over decades. Their effectiveness relies on a nuanced mix of elements such as supply chain domination, multilateral coordination, the character of the denied technologies, and the targeted countries’ adaptive ability—represented through theoretical models and empirical observations from several case studies.