The Talent Pill, Red or Blue?

What China’s Commentators Are Saying About the New K-Visa

Authors

1. Introduction

On October 1, 2025, the Chinese government implemented a new visa policy to invite STEM talent from around the world to China. The new K-Visa intends to create an ecosystem where “young STEM scholars and researchers” can come to China without an employer’s certificate or sanction, and apply for jobs once they arrive. This ambitious policy proposal, announced on August 25, and brought into effect a little over a month later, is situated in a complex geopolitical environment where talent mobility is becoming central to economic and technological competition.

The K-Visa is different from the previous R-Visa and other visas introduced since Xi Jinping assumed power. The previous R-Visa, according to the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Administration of the Entry and Exit of Foreigners,1 is issued to “foreigners of high talent” who are needed, or specialists who are urgently needed, by the State. The call in 2013, and since then, has been to invest and build up an indigenous technological research and development base in China.

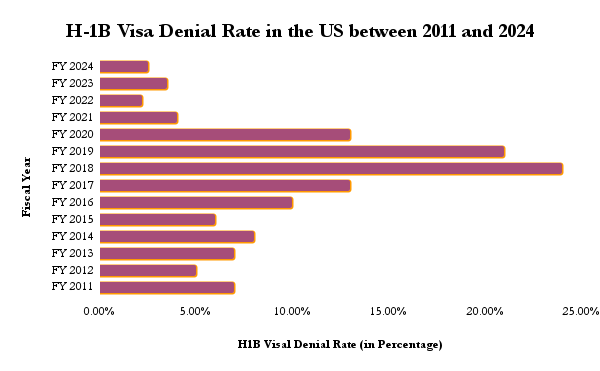

Outside of innovation and growth strategies, the geopolitical moment has potentially provided China’s decision to launch the K-Visa, with an impetus. On September 19, 2025, US President Donald Trump issued a Proclamation, entitled ‘Restriction on Entry of Certain Nonimmigrant Workers,’2 which mandates a US$ 100,000 fee for anyone applying to work in STEM fields in the US through the H-1B visa. In Trump’s first term in particular, H1B visa denial rates were at an all-time high (see Figure 1).3 Today, even as the denial rate has declined, with restrictive policies once again in place during Trump’s second term, STEM talent is likely to choose migration to the US cautiously.

The allure of the H-1B, which conventionally targets all foreign talents in specialty occupations, is traditionally tough to compete with. ~65% of the visa’s applicants (in 2023) have been in “computer-related” jobs, while ~48% sponsoring employers (in 2023) are in the “professional, scientific, and technical services” domains.4 However, deepening nativist grievance and radical changes in American policies under the current Trump administration have opened a window of opportunity. Hence, it is likely that in the Chinese policymaking ecosystem, there is a prevailing sense that this is the time to tap into the high-skilled talent market in the hopes of carving out a significant share.

There are three strands of thought as to how analysts and commentators in China perceive these new regulations. This Issue Brief classifies these arguments as follows:

1.1 The Rivalist-Advocates

The first strand of commentators argues that leveraging the fee on the H-1B visa is a must, and that closing in on the US is the only way to capture the market. This strand of thought also entails optimistic outlooks on the future impact of the K-Visa on China’s growth in STEM domains.

1.2 The Gatekeepers

This is the extremist view on how a policy like this is devastating for a country that has been experiencing six years of economic slowdown. This view primarily comes from the younger population, and those who propound it deride talent coming in from countries like India as “foreign garbage” (洋垃圾), emphasising the linguistic, cultural and informational risks of enabling migration of foreigners to China.

Unemployment among the youth is a deepening concern for the Chinese economy. In the January-September period in 2025, China’s official data puts the overall national urban surveyed unemployment rate at an average of ~5.2%.5 This figure, however, does not capture deeper challenges. Youth unemployment, which captures the age group between 16 and 24, stood at a record high of 20.4% in April 2023, up from 19.6% in March that year.6 By mid-2023, it reached around 21.3%.7 Subsequently, at the time, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) revised its methodology to exclude university students in the unemployment rate calculations, even as it stopped publishing monthly data for the remainder of that year. When publication resumed in early 2024, only the overall national unemployment data was published, and for 2023, the average figure remained at ~5.2% (which the NBS demarcated to be a 0.4% decline from the previous year of 2022).8 Subsequently, for 2024, the average national urban unemployment data was ~5.1%, and no new data on youth unemployment was published.9

This data does not reflect the fact that tens of millions of college students continued to graduate and seek an entry into the workforce.10 In fact, official data informs that next year, the number of China’s university graduates will reach 12.7 million – a new historical high.11 Hence, a lack of existing opportunities may likely be complicated by the freer entry of STEM graduates from across the world into China.

1.3 The Pragmatists

The third strand comes from those seeking to convince the broader public that this move offers greater opportunities for the Chinese population, while acknowledging limitations and the need for regulatory reform. They argue that the K-Visa could be a catalyst for newer jobs, and that regardless of the skill level of foreign talent, there will always be a requirement for local anchors to help them communicate their work, and integrate their methods into Chinese development. Nonetheless, the party-state would have to ensure the mitigation of challenges that come with large-scale immigration, and enforce quality among those who are granted the K-Visa.

2. Thematic Analysis I: The Rivalist-Advocates

The first strand of analysis on the decision of the State Council to introduce the K-Visa, is more optimistic about China’s prospects to become the next global talent hub. They pit this decision against the backdrop of declining American attractiveness for scientific-technological talent, and other countries seeking to capitalise on the opportunities created therefore. Wang Bin, a commentator with a news media platform (Chao News) in Zhejiang province, expressed this sentiment in a September 2025 commentary for Tencent’s QQ:12

“The future of international competition is a competition for talent. Those who acquire talent will win the world; only by winning talent can we win the future. The rise of the United States is inseparable from its attraction of global scientific and technological talent. Now, not only China, but also countries like South Korea, Germany, and New Zealand are relaxing visa regulations to attract skilled workers.”

In essence, he argues that a global “talent war” is quietly underway. Hence, if China aims to gain a greater advantage in the competition for development, it must not only avoid falling behind in the talent competition, but also focus on developing unique strengths and excelling in areas where others lack them.

Writing for Tencent’s QQ, Xi Yun, a commentator with the Guangdong-based platform ‘Business Observers’, agrees:13

“Foreign talent can not only fill labour shortages, but also potentially reshape a country’s innovation ecosystem. The arrival of these talented individuals will not”steal jobs,” but may instead create more jobs. In the increasingly fierce global technological race, whoever can gather the best wisdom is more likely to control the future.”

On the specific issue of the K-Visa, elite opinion in China, represented by state media and government-affiliated analysts, positions the visa as a critical tool for competition for talent mobility with the US. Proponents argue that as the US turns inward – citing 2025 hikes in H-1B fees and stricter scrutiny of Chinese researchers – China must “open its arms.”

Further, the policy is explicitly framed as a counter-narrative to Western “decoupling,” portraying China as the new, inclusive destination for global STEM talent. This is evident, for example, from a September 2025 opinion piece authored by Zhou Chengyi and Hong Junjie,14 commentators with Jiefang Daily, the official daily newspaper of the Shanghai Municipal Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. In it, they argue:

“The more complex the international environment, the more China will open its arms and doors – this is not just empty talk. Perhaps even more directly, the more others try to decouple, the more we must strive to counter decoupling.”

Digging deeper, analysts and commentators speak of three main reasons why eased talent mobility, as enabled by the K-Visa, is not something that should spark concerns among the Chinese populace.

The first reason pertains to the benefits of potential technological breakthroughs that foreign talent may achieve in China. As per a debate published by the Club for International Dialogue,15 a think tank active in Beijing since 2023, the proponents of the K-Visa cite examples of how open talent immigration policies in Europe and the US have fostered originality and innovations in their economies. They explain:

“We must recognise the hidden value of immigrant/outsourcing groups. Turkish and Polish engineers maintain the resilience of German industry, Latin American talent supports the outsourcing of the European and American information industries, and Russian-speaking science and technology talents are active in high-end research and development. These groups, which may face integration difficulties, are natural bridges for the transmission of technology between China and the West.”

The debate further calls for the need to “fully utilise the potential of ‘marginalized technical talent’ in developed countries, and help them return to developing countries to drive industrialisation, thereby accelerating the implementation and application of Chinese-led technical standards in the international market.” Such sentiments essentially veil the intent to systemically enable China’s science and technology predominance, under the garb of creating opportunities for foreign STEM talents.

In this regard, analysts such as Wang Bin also emphasise that, while China has a large number of graduates, the K-Visa, can introduce a “catfish effect”16 – bringing in external talent to stimulate competition and dynamism in the domestic research ecosystem. Interestingly, the articulation of foreign talents previously working in the US or Europe, and now being invited to China, as “bridges for the transmission of technology” to China, also highlights an opportunistic perspective on the K-Visa. It is that even if governments in the West turn sour on the idea of exporting technology to China, the talent that developed those technologies could be imported.

The second reason pertains to bureaucratic confidence. The removal of the invitation letter requirement is touted as a major deregulation achievement, highlighting the state’s confidence in its ability to filter and manage talent post-entry rather than pre-entry.

Thirdly, a niche set of officials also sees the “tourism” value in the visa. Speaking to the state media outlet CCTV, Dai Bin, President of the China Tourism Academy, argued:17

“The issuance of the K-Visa signifies a broader coverage of our visa facilitation efforts, showcasing a more open image of Chinese tourism. It also places higher demands on the convenience of residence, tourism, and daily life for foreigners, especially foreign professionals. Our next step is to create an environment where foreign professionals can come and stay, fostering a comfortable living environment.”

Dai, in particular, has also applauded the measures China has taken to boost tourism and business travel to the country in the past few years. He claims that in December 2024, for example, the National Immigration Administration “optimised” the transit visa-free policy, extending the visa-free stay for foreigners to 10 days and expanding the number of provinces covered by the policy to 24. As of July 17, 2025, China has also achieved full visa-free agreements with 29 countries and unilateral visa-free agreements with 46 countries, continuously expanding its visa-free network. Data from the National Immigration Administration shows that in the first half of this year, 13.64 million foreigners entered China visa-free, accounting for 71.2% of all foreign visitors, a year-on-year increase of 53.9%.

In this backdrop, officials such as Dai consider the K-Visa to be a boost to the tourism ecosystem. This sentiment is also reflected in a blog18 published in October 2025 by the Zhejiang Province’s ‘China Council For The Promotion of International Trade’, wherein the authors critiqued the US State Department’s one-year pilot program for visa security deposits, requiring business and tourist visa applicants from certain countries or regions to deposit up to US$ 15,000. This, the authors believe, is bound to give China an edge in the tourism sector.

3. Thematic Analysis II: The Gatekeepers

Another strand of thought on the K-Visa lies at that extreme end of the spectrum where China’s opening-up measures for foreign STEM talents are viewed as drastic for the economy and society. Proponents of this view shed light on the existence of a sharp disconnect between the Chinese party-state’s goals, and the commentaries of the domestic intelligentsia and the online public. Their opposition to the visa seems rooted in a “China First” mentality, and is driven by concerns around high youth unemployment.

Largely, this stream of commentators focuses on two main challenges of the K-Visa. The first is that the eligibility criteria to avail the visa – a STEM Bachelor’s degree, and the waiver of the employment certificate criterion – are too low. Chinese scholars and netizens alike have pejoratively labelled potential applicants as “Foreign Garbage” (洋垃圾), i.e., graduates from “mediocre” overseas institutions who cannot survive in their own competitive markets. Popular commentators like ‘Pengcheng Shekou’ on Weibo, and their followers, expand on this sentiment. As Pengcheng stated in a recently released video:19

“A cautionary tale from America’s ‘Indianization’! China must be extremely cautious with the domestic K-visa pilot program, or the consequences will be endless!”

The targeting of Indian talent that may potentially migrate to China by availing the K-Visa, is a common theme in the critiques of the visa policy. Popular science and current affairs writer Xiang Dongliang, in his September 2025 essay for China Digital Times,20 expounds the fear and anxieties that Indian immigrants, in particular, but also large migrant populations in general, trigger in China. He claims:

“People are worried that opening up the country will lead to a large influx of young people with ordinary education from India, Southeast Asia, Africa and other places into China to compete for job opportunities. To give an extreme example: If even one young Indian or Nepalese person who enters China with a K-series visa subsequently finds a job in China and converts it to a work visa, thus taking away a Chinese job, it would be enough to trigger another wave of public outcry.”

A fringe but vocal segment of the online elite opinion, reflected in censored Weibo discussions and aggregated by platforms like ‘Civil Rights and Livelihood watch’ (Minsheng Guancha, 民生观察), also views the visa through a conspiratorial lens. As an October 2025 commentary by editors at MS Guancha highlights:21

“The newly added K-Visa raises thought-provoking questions about the motives behind it. Some opinions speculate that this may be an experimental move by certain domestic forces colluding with the West to promote the so-called ‘Kalergi Plan.’ On the internet, the ‘Kalergi Plan’ is described as a conspiracy aimed at undermining a nation’s main ethnic group through immigration and racial mixing. Although this ‘plan’ is widely regarded as an unverified conspiracy theory, the goals it is said to involve undermining the main ethnic group, creating mixed-race populations, erasing the memory and history of the core ethnic group. It bears troubling similarities to strategies that use immigration policies to subtly alter a country’s demographic structure and cultural identity.”

The narration in this commentary is alarmist, and even refers to the K-Visa as the CPC’s failure to treat its own people right. Further, as discussed above, a majority of the negative sentiment on the issue of the state’s inability to manage foreigners domestically, is directed toward Indians. The MS Guancha commentary also adds:

“Canada’s immigration system faces immense pressure due to social problems caused by Indian immigrants; Singapore’s Indian immigration has created chaos. The United States has also fallen into difficulties due to drastic fluctuations in immigration policy and social antagonism. These cases all warn us that immigration policies require careful planning and management.”

A second cluster of concerns raised by commentators centers on the cultural, informational, and linguistic frictions that a significant influx of immigrants could trigger. China has historically been a low-immigration society; foreign residents made up just 0.1% of its population in 2024, even lower than India’s 0.3%.22 This stands in sharp contrast to many of China’s Asian neighbours: South Korea’s foreign population constituted 3.5%, Japan’s 2.8%, Thailand’s 4.4%, and Malaysia’s 10.7%. Immigrant-majority or immigrant-intensive societies show even starker differences. Singapore’s population was 48.7% foreign-born; the United States, 15.2%; Canada, 22.2%; the United Kingdom, 17.1%; Germany, 19.8%; and Australia, 30%. The highest concentrations of immigrants globally are found in the Gulf states, where foreign residents range from 45% to 75% of the population, with Qatar topping the list at 76.6%.23 Against this backdrop, Chinese analysts argue, even a modest rise in foreign arrivals could introduce forms of social and cultural adjustment that China has not previously needed to confront.

In this regard, the state is likely to face challenges in managing the societal changes that massive immigration entails. To begin with, on the information front, commentators express concern about the information flows a sizeable immigrant population will create and how they will likely clash with China’s controlled information and policy environment.

While domestic media rarely uses the term “Firewall” directly, an article appearing in Sina Finance, authored by Qiao Yue,24 cites Associate Professor Wei Huaying of Capital University of Economics and Business on the issue of why the K-Visa may not be a wise policy decision in China’s political environment. She argues that China’s “retention environment” is weak compared to its “attraction policy,” specifically noting that true competitiveness requires “institutional flexibility and trust” (制度的灵活性与信任度) — a euphemism often used in Chinese policy circles to encompass information openness and administrative transparency.

Beyond China, a similar sentiment is expressed by a New Zealand-based Chinese-origin professor in an August 2025 article by The Straits Times. Professor Marina Zhang explicitly identifies “censorship” (Great Firewall) alongside “intellectual property protection” as key factors that would “blunt the appeal” of the visa for talent from advanced democracies.25

Similarly, speaking to the Chinese edition of Radio New Zealand, Dr. Lu Fengming of the Australian National University argues:26

“Many East Asian countries, such as China, Japan, and South Korea, have historically developed a national identity dominated by a single ethnic group. Chinese tech companies are notorious for extremely long working hours, widely known as the”996” work culture - meaning 9 am-9 pm, six days a week. [And] language barriers would also be a challenge for applicants, particularly for those who wanted to start businesses in the country.”

In this regard, sustained differences in working cultures, as well as informational and linguistic preferences, as Chinese commentators believe, would hinder conditions of possibility for the K-Visa to be successful.

4. Thematic Analysis III: The Pragmatists

A third set of analysts and commentators attempt to find the middle ground between the two abovementioned extremes of great optimism and drastic pessimism. This more moderate camp situates the K-Visa within a broader trajectory of China’s talent-driven developmental strategy. Unlike the critics who view the policy as a radical departure from established norms, or the optimists who imagine it as an unqualified breakthrough, these analysts emphasise continuity. They do this by arguing that China has long expressed interest in attracting high-quality human capital, but is now being forced to accelerate reforms in response to slowing economic growth and intensifying global competition. From this vantage point, the K-Visa is less a disruptive experiment than an incremental adjustment that can succeed if paired with robust regulatory oversight. Their arguments often highlight both the policy’s necessity and its risks, offering a pragmatic approach to encouraging public acceptance without glossing over the challenges inherent in large-scale immigration governance.

Essentially, such analysts attempt to assuage concerns and highlight the bright side now that the policy is implemented, but also caution that the party-state must undertake important reforms to ensure enforcement is smooth sailing. A few commentators like Xiang, writing for China Digital Times,27 express this acceptance and still attempt to argue that it is possible the Visa pushes not just China’s overall growth in STEM fields, but also enhances the lives and livelihoods of Chinese citizens. He says:

With the relevant legal amendments to the entry policy already formally passed, the implementation of the K-Visa is inevitable, and no amount of opposition or questioning can make the regulations withdrawn. Whether it’s good or bad for each individual Chinese person depends on their level of professional competitiveness.

Further, this school of analysts also defends the state’s ability to manage a massive influx of immigrants and balance the seemingly low entry barriers. As a commentary by Li Hangyu for the China Daily, published in late October 2025, explains:28

“It is understood that while the required documents for foreigners applying for Chinese visas are not as complex as those for some other countries, the review process is still very rigorous. For example, legally required documents for work and student visas, such as work permits and enrollment notices, must be verified on a case-by-case basis with the issuing authorities in China. Even documents like invitation letters, which have a broad range of issuing bodies, require verification with the inviting organisation or individual in China. Sometimes, relevant domestic departments will be asked to conduct on-site visits to confirm the information. Important documents such as foreign degree certificates required for K-Visa applications will certainly not be accepted without any verification; there is no need to worry about this. Of course, the specific methods cannot be disclosed, and we hope that you understand.”

Addressing citizens’ concerns about foreigners taking Chinese jobs, analysts seek to show how talent immigration can complement local Chinese talent and drive economic growth. The latter will inevitably create more opportunities for locals to prove their mettle. This sentiment is expressed in an opinion piece by Zhou Chengyi and Hong Junjie for Jiefang Daily.29 They claim:

“The job market is not stagnant or static. The knowledge spillover effect brought about by young scientific and technological talents can actually promote economic and social development and release even greater employment opportunities. Foreigners holding K-Visas can engage in scientific research, education, entrepreneurship, and related business and cultural activities, which will also create more job opportunities and expand the employment ‘pie’.”

In a piece for China.com, Zhou Mi expands on this rationale. He explains:30

“Some commentators worry that the influx of skilled workers into China following the implementation of the K-Visa will impact the Chinese job market. However, it should be recognised that as a populous nation, ensuring and creating employment opportunities has always been a top priority for the Chinese government. The continued progress of related work and the anticipated improvement of supporting and regulatory systems will minimise the impact of the K-Visa on the job market.”

Certain commentators even defend immigrants, and express pride in the idea that China could be an option for global talent. However, they argue that management and law enforcement are required for the K-Visa to prove effective. As an October 2025 article on the Chinese social media platform Bilibili puts it:31

“Immigrants are often easily targeted and become the focus of public criticism, but they are also often the most innocent and vulnerable group. The essence of the problem lies in immigration management and governance, and effective policy direction and responsible supervision are urgently needed. After all, the farces caused by immigration issues in Europe and America, which have been ahead of China for over 70 years, provide a cautionary tale.”

Hence, commentators from this school of thought note that China’s demographic and labour-market realities make a rigidly exclusionary approach increasingly untenable. With a shrinking working-age population and rising pressures to innovate,32 achieving global competitiveness will require tapping into international flows of STEM talent. In this regard, they argue, the K-Visa reflects recognition that China cannot sustain its ambitions in science and technology with internal resources alone. However, they also warn that simply attracting foreign talent is insufficient, and the party-state must simultaneously build cultural integration and expand opportunities for local workers.

5. Conclusion

According to many Chinese commentators, the K-Visa should be assessed less as a functional immigration policy and more as a geopolitical signalling device. Its success will likely depend not on mass uptake, but on its ability to attract a small, symbolic cadre of high-profile researchers to validate China’s status as an inclusive and welcoming scientific superpower.

This, however, does not negate the fact that public sentiment against the K-Visa is highly gloom-ridden. Despite the existence of a strand of thought that accepts the implementation of the Visa and advocates for its advantages, many analysts point out the inabilities of the party-state to face the openness a huge foreign population requires, manage the low entry barriers provided for by the K-Visa, solve for local unemployment, and balance the societal clashes between citizens and immigrants.

The contradictions in perceptions are evident. On the one hand, online hate and pessimism are targeted against talent from countries like India in the context of the discussions on the K-Visa. On the other hand, many commentators express an understanding that in the US, or European economies, immigrants have produced outstanding results from economic and technological growth.

As the K-Visa has generated divisive views, the policy has been implemented, and many analysts also accept it as reality. In this context, the way forward, as they advocate, is to ensure regulatory capacity and oversight, and clarify the qualitative requirements for universities and employers accepting K-Visa immigrants. But even as China leverages the geopolitical moment and materialises its quest for the world’s best STEM talent, at the cultural, linguistic and societal levels, the consequences of the policy are bound to create heated debates and hefty resource requirements.

Acknowledgments: The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to Manoj Kewalramani and Shambhavi Naik for their valuable research guidance.

Footnotes

Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Administration of the Entry and Exit of Foreigners, National Immigration Administration, People’s Republic of China, 10 March 2021. Link.↩︎

Restriction on Entry of Certain Non-Immigrant Workers: A Proclamation By The President of the United States, White House, 19 September 2025. Link.↩︎

H-1B Petitions and Denial Rates in FY 2024, National Foundation for American Policy, December 2024. Link.↩︎

Andrew Moriarty, Policy Brief: The H-1B Visa Program, Fwd.us, 27 January 2025. Link.↩︎

Wang Pingping, The employment situation remained generally stable in the first three quarters, National Bureau of Statistics, 20 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Anushka Saxena, PLA lashes out at the G-7 partners & Wang Wenbin lashes out at Liz Truss, Eye on China, The Takshashila Institution, 23 May 2023. Link.↩︎

Barclay Bram, The 19 Percent Revisited: How Youth Unemployment Has Changed Chinese Society, Asia Society, 3 September 2025. Link.↩︎

Wang Pingping, The overall employment situation is stable, and employment for key groups continues to improve, National Bureau of Statistics, 18 January 2024. Link.↩︎

Xinhua, China maintains stable employment in 2024 with lower unemployment rate, The State Council, The People’s Republic of China, 17 January 2025. Link.↩︎

Luna Sun, “China’s graduates set for another difficult year as job market heats up, firms ‘never want candidates with no experience’,” South China Morning Post, 7 April 2023. Link.↩︎

Manoj Kewalramani, What’s the Direction of Economic Policy in 2026?: Central Financial & Economic Affairs Commission Officials Explain CEWC Outcomes, Tracking People’s Daily, 17 December 2025. Link.↩︎

Wang Bin, “Commentary | China’s K-type visa sparks heated discussion: Only by moving beyond narrow-mindedness can we achieve long-term success,” Trendy News on QQ, 30 September 2025. Link.↩︎

Xi Yun, “Are Indians coming to “steal jobs”? China’s opening of K visas has far more impact than imagined,” Business Bystanders on QQ, 5 November 2025. Link.↩︎

Zhou Chengyi and Hong Junjie, “Commentary from Shangguan Times: Are Indians Coming to China to Steal Jobs? Don’t Misunderstand China’s K Visa,” Jiefang Daily, 29 September 2025. Link.↩︎

“The “K visa” sparks heated debate: How exactly will the talent war be fought? | Multiple perspectives,” Beijing Dialogue Club on QQ, 9 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Wang Bin, “Commentary| China’s K-type visa sparks heated discussion: Only by moving beyond narrow-mindedness can we achieve long-term success,” Trendy News on QQ, 30 September 2025. Link.↩︎

“The K-visa is here! Making it easier for young foreign science and technology talents to come to China,” CCTV, 15 August 2025. Link.↩︎

The stark contrast between Chinese and American visa policies has sparked curiosity among foreign media regarding China’s “K” visa, Information Service Department: China Council for the Promotion of International Trade, Zhejiang Provincial Committee, 10 October 2025. Link.↩︎

“美国 “印度化” 前车之鉴! 国内K签证试点必须谨慎, 否则后患无穷,” Pengcheng Shekou on Weibo, 28 November 2025. Link.↩︎

Xiang Dongliang, “Constructive feedback | The K visa, designed to attract foreign talent, is a good thing, but it’s been launched at the worst possible time,” China Digital Times, 30 September 2025. Link.↩︎

“The public’s anger over the K visa reveals the CCP’s totalitarian nature and its disregard for people’s livelihoods,” Civil Rights and Livelihood Watch: MS Guancha, 7 October 2025. Link.↩︎

“Is China opening up K-type visas, and will Indians soon flood in to exploit the country?,” Earth Knowledge Bureau on Bilibili, 1 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Qiao Yue, “K visa is here, are we ready to open it up?,” Sina Finance, 17 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Michelle Ng, “China’s new K visa for young Stem talent signals ambition, but also anxiety, say analysts,” The Straits Times, 23 August 2025. Link.↩︎

Kai Feng, “China’s K visa scheme has some worrying about jobs in a country already facing challenges,” Radio New Zealand, 3 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Xiang Dongliang, “Constructive feedback | The K visa, designed to attract foreign talent, is a good thing, but it’s been launched at the worst possible time,” China Digital Times, 30 September 2025. Link.↩︎

Li Hangyu, “Commentary | K-type visa sparks heated discussion; 科普 post: Let’s talk about visa processing,” China Daily, 6 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Zhou Chengyi and Hong Junjie, “Commentary from Shangguan Times: Are Indians Coming to China to Steal Jobs? Don’t Misunderstand China’s K Visa,” Jiefang Daily, 29 September 2025. Link.↩︎

Zhou Mi, “[China.com Commentary] Why does China implement the “K visa”?,” China.com, 6 October 2025. Link.↩︎

“Is China opening up K-type visas, and will Indians soon flood in to exploit the country?,” Earth Knowledge Bureau on Bilibili, 1 October 2025. Link.↩︎

Amit Kumar, “India is well placed to become the ‘next China’ and drive global growth,” Nikkei Asia, 9 August 2024. Link.↩︎