Executive Summary

Megaconstellations dominate the Low Earth Orbit. With falling launch costs, companies like SpaceX are rapidly launching satellites to create megaconstellations. Today, over 70% of all active satellites are megaconstellations, and they are still only in the initial stages of deployment. This burst of activity is entrenching the LEO.

Author: Ashwin Prasad is a Staff Research Analyst with the Advanced Military Technologies and Outer Space Programme at the Takshashila Institution. He can be reached at ashwin@takshashila.org.in.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Aditya Ramanathan for his invaluable comments and feedback.

Disclosures: AI tools were only employed to assist with document layout (LaTeX) and citation formatting.

This document has been formatted to be read conveniently on screens with landscape aspect ratios.

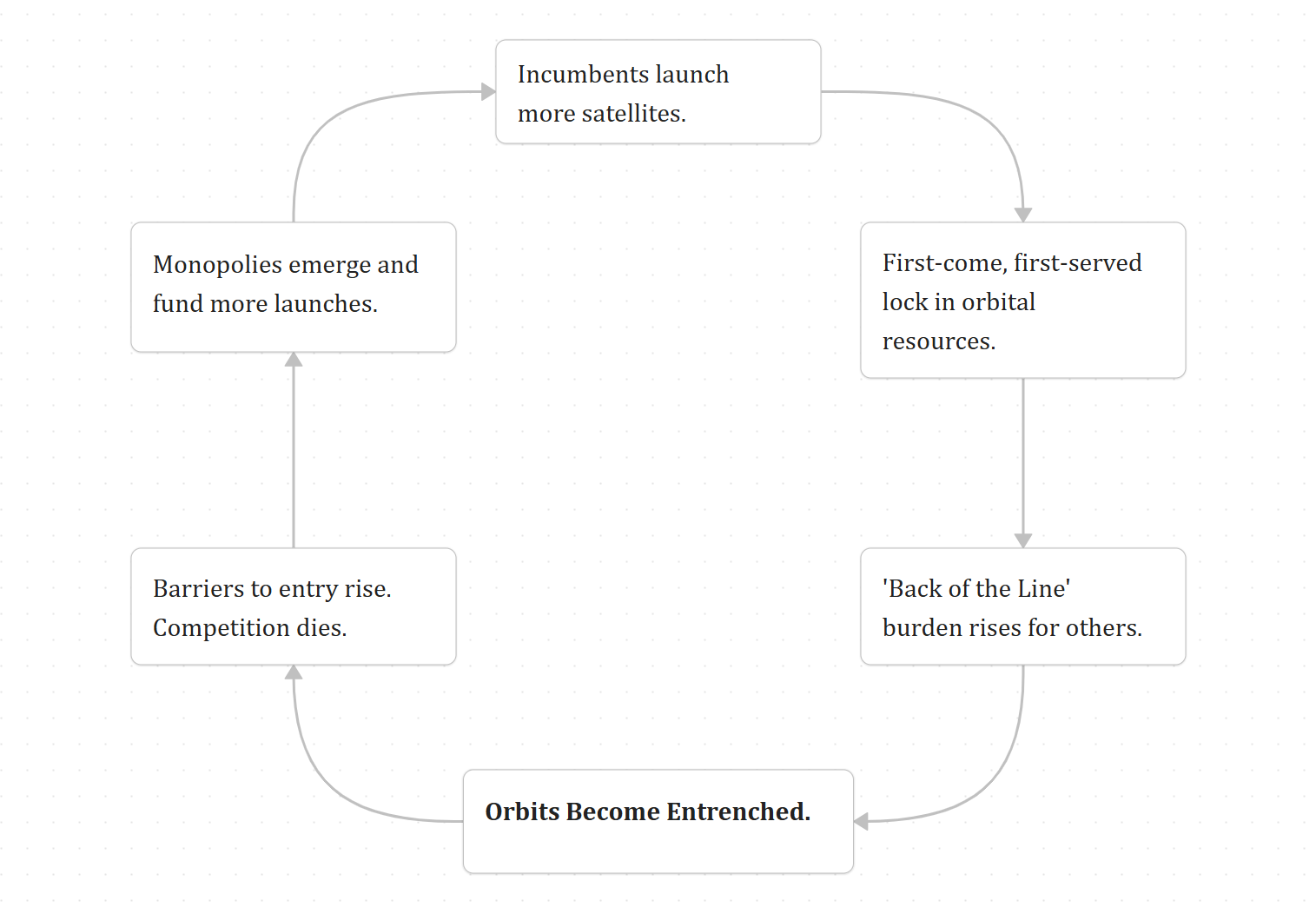

Under current regulations, the first to launch wins the race. The International Telecommunication Union’s first-come, first-served rules allow early movers to lock up the best orbits and frequency resources, and hold them in perpetuity. The megaconstellations are exploiting this system to make LEO functionally theirs. All later entrants are forced to operate and coordinate around early megaconstellations, or migrate to less favourable orbits.

Importantly, this incumbency is effectively permanent. Operators can hold these rights in perpetuity as long as they continuously replace old satellites. This dynamic creates a ‘back of the line’ problem—locking out startups and future generations of the developing world from prime, low-orbit resources.

If left unchecked, the technology that can connect the world will fragment it instead. It will deepen geopolitical fault lines into the orbits and become a fresh cause for technology denial and economic coercion. Preventing this necessitates a redesign of the rules.

This paper proposes five measures:

- Establish a multilateral mechanism that charges a ‘rent’ for orbits to price in congestion and risk;

- Form plurilateral alliances that pool resources, markets and bargaining power to counter monopolies;

- Implement degrees of interoperability through standards;

- Strengthen the ITU to grant time-bound orbital rights, instead of perpetual ones, and

- Establish ‘clubs’ where major powers commit to safety and sharing protocols.

1. Introduction

Lightning rarely strikes from a single cloud; it emerges when atmospheric conditions align—moisture, temperature, and electric charge converging in harmony. So it is with technology. World-changing breakthroughs materialise when synergistic technologies simultaneously reach critical mass. Satellite internet is a relevant example. With progress in rockets, signals, and semiconductors, SpaceX’s Starlink managed to harness the perfect commercial opportunity in a world that hungers for the internet.

SpaceX has an implied valuation of USD 400 billion. That makes it the world’s most valuable private company.1 Its position in the global space economy is undisputed. A considerable part of this is owing to Starlink. Leveraging reusable rockets and vertically integrated manufacturing, SpaceX has rapidly launched thousands of satellites into LEO, thereby forming a megaconstellation. As a network, they provide low-latency, high-bandwidth internet connectivity to users on the ground. This marks a new approach to satellite internet that has found purchase. Starlink has over 8 million active customers from more than 150 countries.2 It is finding demand in developed and developing countries alike—across a myriad of civilian and military use cases.

LEO (Low Earth Orbit) is an orbital path centred on the Earth, with an altitude of 2,000 km or less. It is the region most used for satellite internet due to low latency.

A Megaconstellation is a network consisting of hundreds or thousands of satellites working together as a system to provide global coverage.

Latency is the time it takes for data to travel from a source (Earth) to a destination (satellite) and back. LEO satellites offer ‘low latency’ because they are closer to Earth.

Bandwidth refers to the network’s capacity to transmit large volumes of data simultaneously. Unlike early satellite systems—that could only handle slow, text-based data—modern high-bandwidth LEO constellations (like Starlink) can support data-intensive activities like 4K video streaming, video conferencing, and large file downloads.

Read my first paper that covers these features in detail: Satellite Internet Explained

With its inherently global and penetrative nature, satellite internet can be quickly set up virtually anywhere on the globe. The capabilities it brings have the potential to shape the global economy and military strategy. The reach and scope of a satellite megaconstellation require assets and operations on a scale that has not been seen in previous space technology endeavours.

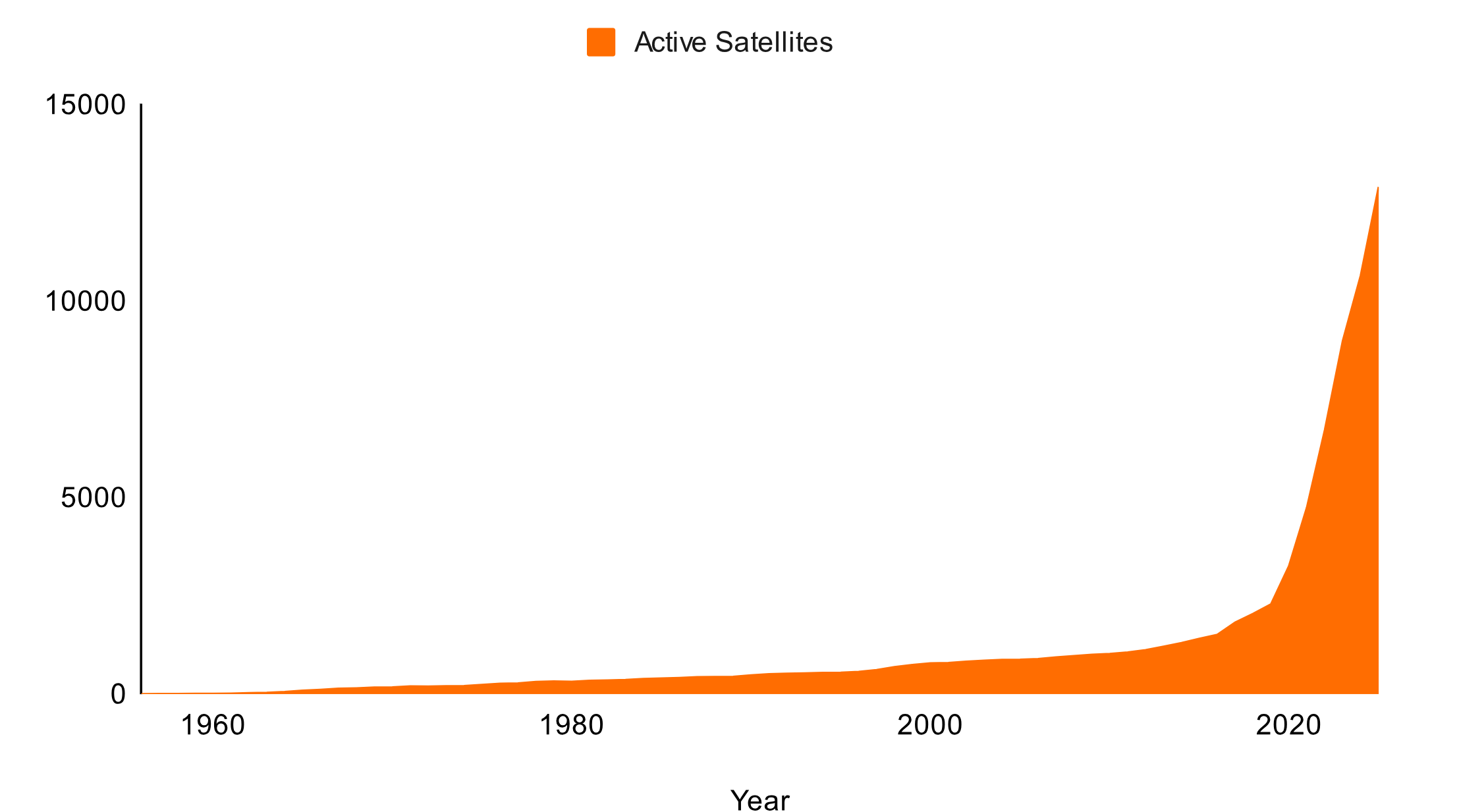

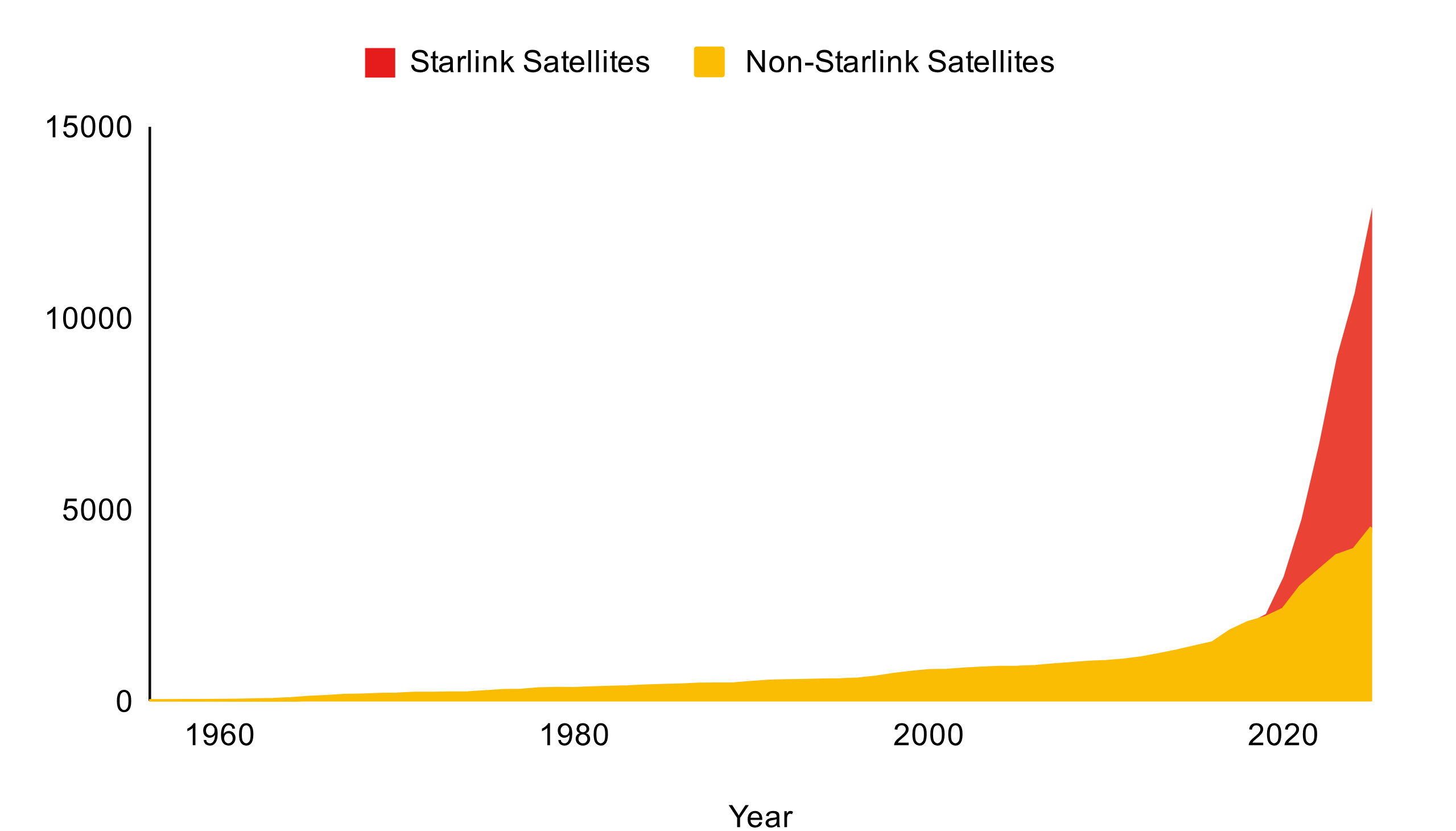

The unprecedented scale is reflected in the trends that show the number of active satellites over the years. In the chart below, we see a sharp spike in active satellites after 2018.

When examining the same chart after breaking up all the active satellites into Starlink and Non-Starlink categories, we realise that the surge can be attributed to Starlink alone.

SpaceX has launched more satellites in the last five years than in the first 50 years since Sputnik. Over 60% of all active satellites are Starlink satellites. Over 70% of all active satellites are internet megaconstellations. These constellations are all still in the initial stages of their planned total deployments.5

This extraordinary burst of satellite activity in LEO comes with consequences. The part of outer space around the Earth—often referred to as Earth-space—is not unlimited. LEO is a part of Earth-space. The megaconstellations are rapidly using up the orbital resources of the LEO. This creates two kinds of scarcity. First, the physical space that the satellites operate in. Second, the Radio Frequency Spectrum that the satellites use.

Radio Frequency (RF) Spectrum is the range of electromagnetic wave frequencies used for wireless communication.

In addition to being limited, these orbital resources are shared by all humanity. No one state can claim ownership over them; nor can any country legally prevent another from accessing them. Consequently, we are left with a system where there is a gold rush within LEO amongst a handful of players, leaving less for the rest. Therefore, megaconstellations represent Orbital Entrenchment of the LEO. By virtue of their massive scale of occupation and operation, they saturate the orbit—effectively shutting others out.

I use the term ’Orbital Entrenchment’ in this paper to describe the process by which early movers in space solidify their dominance through scale and regulation, effectively raising the barrier to entry for latecomers.

The megaconstellations promise transformative gains for global connectivity and information flows. However, their unchecked proliferation will create a crisis of orbital resource scarcity, with control concentrated in the hands of a few corporations and countries. This necessitates coordinated technical and political interventions to ensure long-term, equitable access to space.

This is the second paper in a series addressing these issues. It begins by outlining the mechanisms of Orbital Entrenchment, looking specifically at physical orbital resources and radio frequency resources. From there, it examines the global repercussions of this entrenchment before proposing governance solutions.

2. The Onset of Early Orbital Entrenchment

The range of geographical domains that countries attempt to control is partly a function of technology. With progress in technology, countries are able to penetrate and wield control over new domains. For example, states now have greater capacity to exert control over their territorial waters and airspace.6 This became possible with advancements in radars, ships, and surveillance technologies—allowing countries to monitor the sea and air more effectively. Outer space, however, is different, both because of technological limitations and international politics which have emphasised unfettered access to space.7

When the space age began, countries began to access outer space without any way of preventing others from accessing it too. People claim that Sputnik—the first satellite to be launched—was distinctly visible to the naked eye, as it zoomed past the US landmass.8 Anti-satellite technologies were later developed to shoot down or disable an adversary’s spacecraft.9 However, both the US and USSR had an interest in allowing orbital overflight by reconnaissance satellites. Clearly delineated control zones in Earth orbit were impossible to achieve, given the levels of technological progress during the Cold War.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty also reflects these technological and political realities. It forms the sole foundation of the legal framework for governing space activities around the world. The OST was written before the commercial value of orbital slots was fully understood. It prohibits national appropriation (planting a flag) but allows for use (launching a satellite). This distinction effectively allows for the occupation of valuable orbital slots, as long as a country claims they are just ‘using’ the slot rather than ‘owning’ it. 10

Outer Space Treaty (OST) (1967) is formally known as the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. It is the constitution of space law. It declares that space is the ‘province of all mankind’.

Recent technological advancements and the emerging satellite megaconstellations are harbingers of a new reality in the LEO. Cheaper and reusable rockets can launch satellites into orbit at a greater cadence. Very few entities around the world are capable of making rockets that return.11 Those that do are using that technological advantage to launch megaconstellations into LEO. The sheer volume of physical and radio frequency resources they use leaves diminished capacity for future entrants. The following sections discuss this scarcity of physical and frequency resources in detail.

2.1. The Physical Resource in Orbits

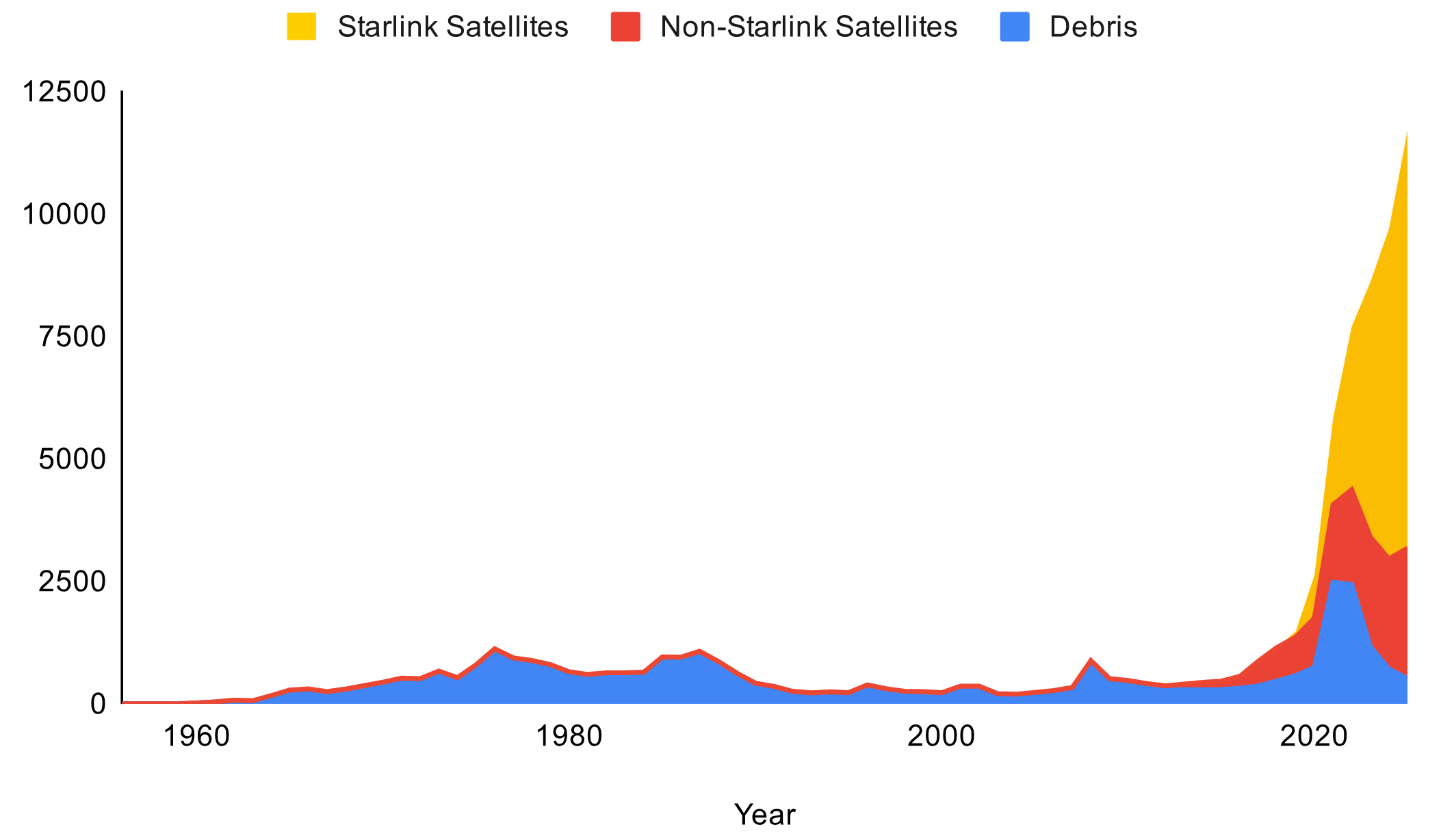

The LEO spans altitudes of 2,000 km above the Earth’s surface. However, the functional reality of the LEO is much more compressed. The vast majority of the megaconstellation activity is in orbits below 600 km. This region has become the densest by population. Being the closest part of space around Earth—and for that reason, the smallest—the carrying capacity of this part of LEO is very limited. This constraint is tightened further by a vast population of inert, largely untracked debris. The graph below shows the various objects in the LEO.

Orbital carrying capacity is the theoretical maximum number of satellites that can safely operate in a specific orbital shell, without causing a cascade of collisions.

Debris (Space Debris) are defunct human-made objects in space, which no longer serve a useful function.

Recent analysis of the June 2025 satellite catalogue reveals a worrying trend. The density of objects in the primary Starlink orbits (around 550 km) is now an order of magnitude higher than the peak density of tracked space debris. We have effectively created artificial debris fields denser than the remnants of historical collisions.

2.1.1. Carrying Capacity of the LEO

Only a certain maximum number of satellites can coexist in this orbit at any given point in time. But what is that maximum number? Modelling studies have attempted to answer that question. Models such as the MIT Orbital Capacity Assessment Tool show that theoretically, around 12 million satellites can coexist in the LEO—but only under near-ideal conditions. It assumes a low satellite failure rate and quick and reliable space debris removal.13 Another study argues that LEO can only accommodate 175,000 satellites with realistic safety margins.14 Science reporting that draws on orbital dynamics experts, including researchers at institutions such as the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, often quotes an even lower number. An upper limit of roughly 100,000 active satellites in LEO is what they recommend for safe, manageable operations under current practices.15

Right now, there are around 14,000 active satellites in total. Over 90% of these are in the LEO. Over 70% of these are internet megaconstellations. These include Starlink, Project Kuiper (renamed to Leo), OneWeb, Qianfan, GuoWang, AST SpaceMobile and many others. All of them operate in the LEO. Currently, all of these networks are still in the initial phases of deployment, as shown in the table below.16

| Constellation | State | Active Satellites | Planned Size | Completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starlink | US | 9,093 | 41,584 | ~22% |

| Kuiper (Leo) | US | 155 | 3,232 | ~4.8% |

| OneWeb | UK | 648 | ~7,000 | ~9% |

| Qianfan (G60) | China | 108 | ~15,000 | < 1% |

| GuoWang (Xingwang) | China | 133 | 12,992 | < 1% |

| AST SpaceMobile | US | ~5 | 243 | ~2% |

| Lynk | US | 10 | 2,000 | < 1% |

| Yinhe | China | 8 | 1,000 | < 1% |

| Cinnamon (E-Space) | Rwanda | 0 | 3,37,323 | 0% |

| Semaphore (E-Space) | France | 0 | 1,16,640 | 0% |

| Hanwha | South Korea | 0 | 2,000 | 0% |

| Telesat | Canada | 0 | 298 | 0% |

| Hughes | US | 0 | 1,440 | 0% |

| Honghu | China | 0 | 10,000 | 0% |

| Astra | US | 0 | 13,620 | 0% |

| SpinLaunch | US | 0 | 1,190 | 0% |

| Globastar | Germany | 0 | 3,080 | 0% |

Source: Author’s compilation based on ITU filings and data from J. McDowell, planet4589.org.17 The list is not exhaustive.

These megaconstellations are on a clock. Under ITU regulations, operators must reach their full planned sizes within the next decade.18 Otherwise, they forfeit the rights to any unused capacity. Counting just the megaconstellations that have active operations to reach the targets, the total number of satellites—just from the internet megaconstellations—will exceed 80,000 as soon as 2035.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union) is the United Nations specialised agency responsible for all matters related to information and communication technologies, including the coordination of global radio spectrum and satellite orbits.

In just a decade, the satellite numbers are approaching the modelled maximums. If humanity can go from 12,000 to well over 80,000 satellites in LEO from 2025 to 2035, what will be the rate of growth in the decade that follows? With further progress in rocket technology, we can expect an even higher growth rate.

Even before we begin to approach the carrying capacity numbers, satellite operators will be forced to confront a more challenging environment in the LEO. The ITU regulation places the onus on the new satellite to operate around the existing satellites, without interfering with them. In essence, every satellite comes with a Keep-out Volume. Everyone else must steer around this footprint. Therefore, every additional satellite has a harder time than its predecessor.

Keep-out Volume is the safety zone of empty space that must be maintained around a satellite to prevent collisions and interference.

2.1.2. Measuring the stress from Megaconstellations

Carrying capacity is a useful measure of the extent to which the emerging megaconstellations will populate the LEO. However, its usefulness is limited in measuring the consequences of the increased satellite density. Analogies comparing orbital resources to ‘parking spots’ do not paint an accurate picture. Even in a purportedly crowded section of the orbit, satellites traverse a vast emptiness.

The constraint is not the physical lack of volume, but the probability of collision. Safety in the LEO depends almost entirely on continuous, error-free manoeuvring rather than physical spacing. Satellites are akin to autonomous cars travelling at blinding speeds with little manoeuvrability.

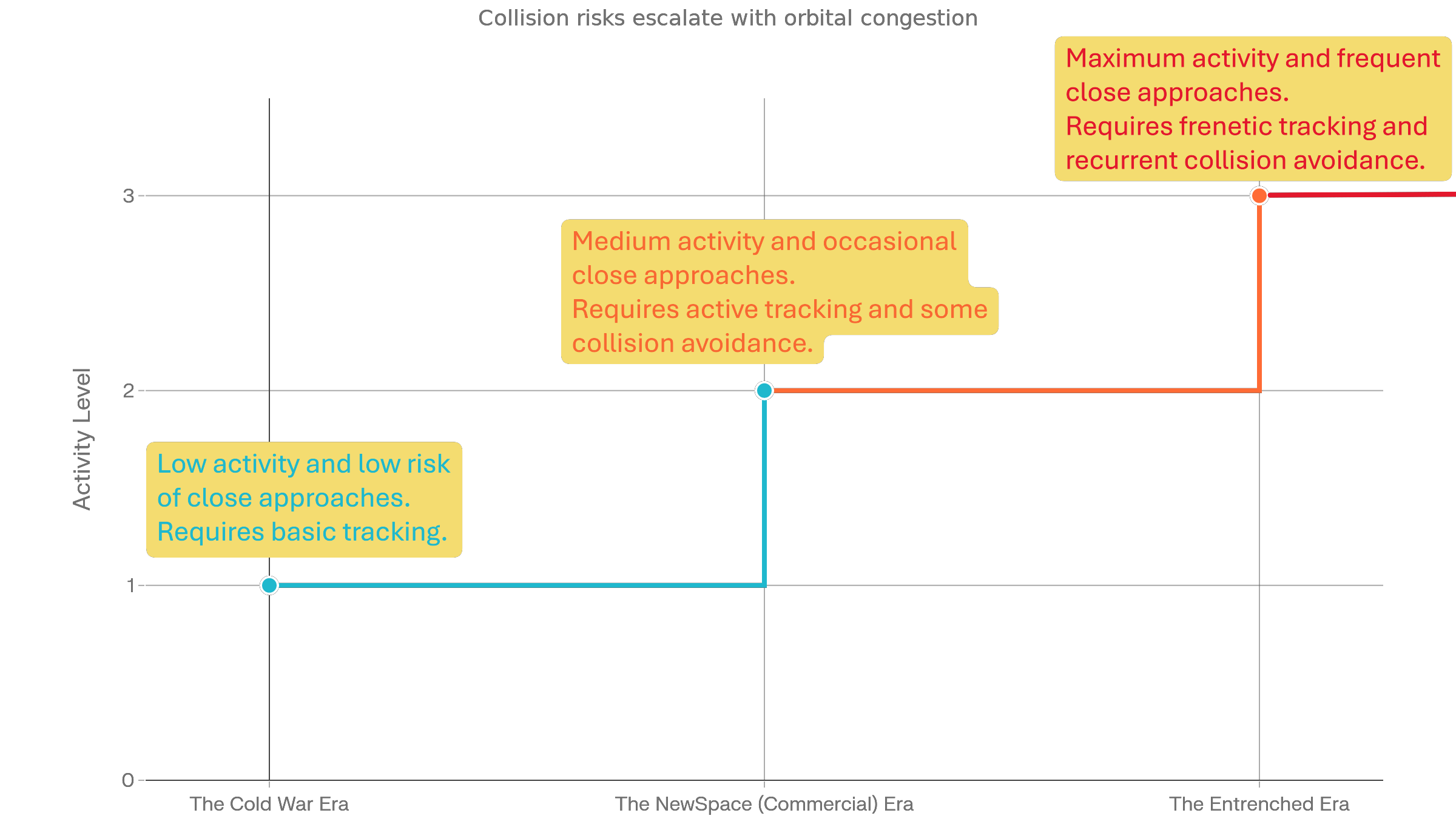

Every additional satellite in the LEO raises the Entropy, a measure of the increasing disorder and risk within the environment. A recent study attempts to quantify this entropy by measuring how long we have until a catastrophic collision if satellite manoeuvring suddenly stopped. They call it a ‘Crash Clock’. The deterioration of this metric is extremely stark. Before the megaconstellations, the clock stood at 121 days. By June 2025, it had collapsed to just 2.8 days.19 This is a serious cause for concern. The system is no longer ‘passively’ safe. It requires constant, error-free intervention to prevent disaster.

I use the term, Entropy in the paper to describe the increasing disorder, complexity, and risk of collision within the orbital environment as more objects are added.

As the number of satellites grows, close approaches are becoming routine. In the densest parts of the LEO, a close approach of less than 1 km now occurs every 11 minutes.20 The number of Collision Avoidance Manoeuvres has risen in lockstep. Starlink satellites conducted nearly 25,000 Collision Avoidance Manoeuvres in just the six-month period from December 2022 to May 2023, double the number of manoeuvres in the previous six months.21 From December 2024, to May 2025, this has increased to 144,404 collision avoidance manoeuvres. An average of approximately one manoeuvre every 1.8 minutes across the Starlink megaconstellation.22

Collision Avoidance Manoeuvre: A controlled firing of a satellite’s thrusters to alter its path, and prevent a potential crash with another satellite or debris.

The danger of this high-frequency maneuvering environment is that it assumes perfect control. In 2019, a ‘bug’ in the Starlink system prevented them from spotting a high probability collision event with a European Space Agency’s (ESA) satellite. The ESA undertook an emergency collision avoidance manoeuvre to avoid the potential crash.23 Perfect control is improbable to maintain in today’s manually coordinated, multi-stakeholder systems. External events can make it impossible as well. The Gannon Geomagnetic Storm in May 2024 caused atmospheric density to spike. The higher air density in LEO increased the atmospheric drag so severely that more than half of all active satellites had to manoeuvre simultaneously to maintain orbit.24 During such events, entropy massively increases, making collision predictions less reliable.

We are currently in a system where the margin for error is razor-thin. Models show that the 550 km orbit is now so crowded that a single collision could trigger an unstoppable chain reaction.25 All of these conditions raise the sophistication threshold required to launch satellites to LEO. It will become technologically, economically and politically costlier. If these trends persist, space operators with lower levels of capability may be unable to access and safely operate in orbit. The incumbents with more developed capabilities will enjoy a lead that may widen over time. This will force all later entrants to coordinate around them, accept tighter performance and safety constraints, or migrate to less favourable altitudes and inclinations. This operational reality imposes exclusivity and establishes entrenched interests in orbit.

2.2. The Frequency Resources in Orbit

All wireless devices—be it a phone in your pocket or satellites in space—beam information through invisible, yet important, radio frequency signals. Satellites in orbits beam information downward towards us in the form of radio frequency signals.

2.2.1. Understanding exclusivity and the need for coordination

These ‘beams’ operate using exclusive frequencies. They have to be exclusive in order to avoid overlapping of signal waves. When the ‘peak’ of one operator’s wave meets the ‘trough’ (valley) of the other operator’s wave, they effectively subtract from each other. This creates destructive interference, which reduces the signal strength to zero or creates ‘white noise’.

In the case of telecom, exclusivity is maintained by the government using spectrum auctions. Specific frequencies have been auctioned off to specific telecom providers, and only they can use them. If two telecom operators were to provide the same frequency of 5G signal in the same area, then their individual signals would destructively interfere, and your phone would be unable to distinguish the information from the noise, resulting in dropped calls, no data, or a “No Service” message.

This is also the reason we are all asked to keep our phones in Airplane mode while flying. A phone transmitting signals at altitude could broadcast across multiple cell towers simultaneously, or on frequencies adjacent to sensitive aircraft equipment. The phone’s signal emissions could overlap with the weak radio signals used for navigation or pilot-tower communication. While it might not always cancel the signal completely, it introduces noise that makes the critical information garbled for the pilots.

This need to ensure exclusivity in radio frequency signals exists across all forms of transmissions. Every radio frequency device effectively requires an exclusive lane on an imaginary highway to transmit information from source to destination. This exclusivity of lanes is achieved through coordination. This coordination can be technological, political or a combination of the two.

Technological: Some devices that use signals with similar frequencies and power levels adopt coexistence techniques. It is a form of technology coordination. They coordinate with one another and ensure only one of them uses the highway lane at any given point in time. Bluetooth and Wi-Fi signals are good examples of such coordination. However, these are mostly used for short-range communication.

Political: For reliable, continuous, high-performance communication, coexistence techniques are not sufficient and coordination has to be done politically. Governments step in and auction off entire highways or allocate these highways to specific firms for their exclusive use. Mobile networks, television broadcasts, and military communication networks are all examples of frequency highways that have been cordoned off by the government for exclusive use. There is one other example that gets its own frequency highways—satellites.

2.2.2. The case of satellites and the ITU

Every satellite in orbit requires its own highway lane to send and receive information from the Earth’s surface. Given that the LEO is not limitless, neither is the number of these lanes on the spectral highway. Since satellites transcend the territorial dominion of nation-states, an international coordination framework is necessary to govern orbital spectrum resources. This international limited resource has to be assigned, coordinated and managed, just as governments manage their national frequency resources. This function is performed by the ITU.

The ITU coordinates between the countries of the world and facilitates cooperation for the sake of RF signal non-interference in the course of each country’s space activities. As laid out in its constitution, its core mandate is two-fold. First, to coordinate efforts to eliminate harmful interference between radio stations of different countries. And second, to ensure the rational, equitable, efficient, and economical use of the radio-frequency spectrum and associated satellite orbits. Through its Radiocommunication Sector (ITU-R), the ITU administers the Radio Regulations—an international treaty that governs how these shared resources are used.26 The ‘ordinariness’ of this specialised agency masks its criticality.

ITU (International Telecommunication Union) is the United Nations specialised agency responsible for all matters related to information and communication technologies, including the coordination of global radio spectrum and satellite orbits.

The ITU has 194 Member States, which include virtually every sovereign nation on Earth (even more than the UN itself in some counts). Founded in 1865 (originally for the telegraph), it is the oldest intergovernmental organization in the world. It predates the UN, the League of Nations, and the automobile.

No country can easily operate a satellite network without ITU recognition. If you launch a satellite without ITU coordination, your signals may be jammed by others, and you will have no legal recourse. The ITU MIFR (Master International Frequency Register) is effectively the ‘title deed’ registry for the sky.

Unlike most UN bodies, the ITU allows private companies like SpaceX, Boeing, and Huawei to sit at the table alongside governments. This makes it the only venue where the regulators and the regulated directly negotiate the technical future of humanity.

In practice, there’s a clear, multi-step administrative process for securing international recognition to use specific frequencies and orbital resources. An operator, acting through its national administration (e.g., the FCC in the United States), first submits an Advance Publication Information (API) filing to the ITU—essentially a public notice of intent to use certain ‘lanes’ in the spectral highway. Next comes Coordination: the filing administration must work with any administrations of existing, or previously filed, systems that could be affected by interference. They negotiate technical and operational arrangements so that the proposed lane can be used without disrupting those already in the traffic flow. Once the necessary coordination agreements are in place, the administration submits a final Notification. If this conforms to the Radio Regulations, the network’s frequency assignments are recorded in the Master International Frequency Register. That recording is what grants the system international recognition—and with it, the right to operate free from harmful interference caused by subsequent systems.27

FCC (Federal Communications Commission) is the United States government agency that regulates interstate and international communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable.

The Master International Frequency Register (MIFR) is the international database maintained by the ITU that records frequency assignments, giving them international recognition and protection.

As evident, the ITU operates on a first-come, first-served basis. Earlier-filed systems have senior rights, and every new system has to play nice with all the older ones. They are legally obligated to coordinate around them and avoid causing them harmful interference. Though this queueing rule looks neutral and orderly on paper, its real-world effect is anything but. Well-resourced early movers can stake a claim over the most valuable orbital and spectral highway, leaving latecomers and developing nations at a structural disadvantage.

Crucially, this incumbency is effectively permanent. Unlike patents or terrestrial spectrum licences, which often expire after a fixed term, an orbital assignment in the MIFR has no expiration date. The operator maintains the service by replacing old satellites with new ones when necessary. They retain their priority rights indefinitely, thereby allowing well-resourced incumbents like Starlink to hold their orbital rights in perpetuity. This brings us to the problem with satellite megaconstellations. We can have only so many usable lanes in our imaginary frequency highways for LEO satellites. The orbital resource is scarce. Every additional lane taken is one less lane for a future satellite. In that sense, the system’s operational effect contradicts the ITU’s own constitutional promise of equitable access for all countries.

The important question and counter that is often asked here is—are the number of possible lanes truly limited? The answer here is that it is a function of technology. In the past, technology has drastically increased the number of lanes and continues to do so. More efficient and capable antennas transmitting at higher frequencies could now use hitherto unused lanes. Multiple access techniques and Spot Beam technologies made lanes narrower. Modulation schemes allowed satellites to pack more information into a single lane. Polarisation Multiplexing allowed the stacking of signals in a single lane. All of these techniques effectively increased the number of lanes in the spectral highway. It is a case of technological coordination alleviating the need for clunky political solutions. It worked because technological advancements outpaced the growth in space activities. They created new lanes faster than we could use them. But satellite internet megaconstellations, with their sheer numbers, threaten to overwhelm this trend in the future.

Spot Beam is a satellite signal concentrated on a small geographical area (rather than a broad beam) to increase signal strength and allow frequency reuse.

Polarisation Multiplexing is a technique used to double the capacity of a transmission ‘lane’ by sending two distinct signals on the same frequency, but with different electromagnetic orientations (e.g., vertical vs. horizontal).

2.2.3. How it is playing out in practice

ITU filings for new satellites were stable till a decade ago. They have exploded since 2016. The inflection point coincides with the first major filings for LEO internet constellations, with such requests escalating by 5.5 times over the past decade.28 Between 2017 and 2022 alone, countries collectively filed for more than one million satellites.29 A share of this is from the well-resourced players hoping to actually launch the satellites they file for. But there is also a share of speculative filings by private entities and countries.

Firms and countries began to realise that the hitherto abundant orbital resources will soon become scarce. The first-come, first-served trap meant that earlier filings would always enjoy advantages over later ones. E-Space used France and Rwanda to make massive speculative filings that the ITU could not turn down.30 Not a single satellite of the nearly 450,000 filings has been launched.31 Yet, for the sake of regulation and coordination of frequency resources in space, they exist. ITU recongnised the loophole and plugged it with a resolution that enforced milestone-based mandates.32 This is not retroactive. E-Space filings are still valid, despite being ‘paper satellites’ that exist only in regulatory filings (to reserve spectrum) but are unlikely to be built or launched.

Most of these filings are concentrated in the LEO and use two bands: Ka-band and Ku-band. The Ku-band and Ka-band ‘lanes’ are the sweet spots that offer the best balance of data throughput, along with weather resilience for satellite communication. An analysis of FCC filings between 2016 and 2024 reveals that 52% of all NGSO applications specifically targeted Ka and Ku bands.33 Another analysis of FCC filings shows that US entities have filed for over 70,000 satellites specifically in the Ku, Ka, and V bands.34 Besides showcasing US dominance in owning these spectrum resources, this is also a sign of the saturation of these ‘lanes’.

NGSO (Non-Geostationary Satellite Orbit) are satellites that do not stay fixed over one point on Earth but move across the sky (includes LEO and MEO). Read my first paper about this topic: Satellite Internet Explained

The weather resilience refers to the ability of the radio frequency signal to resist rain fade, also known as atmospheric attenuation.

The expanded versions of our earlier table outlines the numbers based on ITU records.35

| Constellation | State | Active Sats | Planned Size | Completion | Frequency | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starlink | US | 9,093 | 41,584 | ~22% | Ku, Ka | Dominates prime bands. |

| Kuiper (Leo) | US | 155 | 3,232 | ~4.8% | Ka, V | Forced overflow. Pushed to V-band. |

| OneWeb | UK | 648 | ~7,000 | ~9% | Ku, Ka | Completed first phase. Effectively blocked from expanding. |

| Qianfan (G60) | China | 108 | ~15,000 | < 1% | Ku, Q, V | New entrant. Prioritising Q/V to bypass congestion. |

| GuoWang (Xingwang) | China | 133 | 12,992 | < 1% | Ku, Ka | Active & scaling. May lead to disputes with Starlink in 2026. |

| AST SpaceMobile | US | ~5 | 243 | ~2% | UHF, V | Niche. Uses cellular bands (low freq) + V-band backhaul. |

| Lynk | US | 10 | 2,000 | < 1% | UHF, Ka | Niche. Cellular bands + Ka feeder links. |

| Yinhe | China | 8 | 1,000 | < 1% | Ka, Q, V | Testing Q/V bands for 5G. |

| Cinnamon (E-Space) | Rwanda | 0 | 337,323 | 0% | Ku, Ka | Blocking entry. Massive “paper” reservation. |

| Semaphore (E-Space) | France | 0 | 116,640 | 0% | Ku, Ka | Blocking entry. Massive “paper” reservation. |

| Hanwha | South Korea | 0 | 2,000 | 0% | Ka | Planned; latecomer struggling for slots. |

| Telesat | Canada | 0 | 298 | 0% | Ka | Downsized to 198 to meet ITU’s Regulation 35. |

| Hughes | US | 0 | 1,440 | 0% | V | Filed for V-band to avoid crush. Now dormant due to cost. |

| Honghu | China | 0 | 10,000 | 0% | Ku, Ka | Will be forced to constrained environment. Interruptions likely. |

| Astra | US | 0 | 13,620 | 0% | V | Filed for V-band. No serious plan. Will likely expire. |

| SpinLaunch | US | 0 | 1,190 | 0% | Ku, V | No plan. Only junior rights; service would be erratic. |

| Globastar | Germany | 0 | 3,080 | 0% | No serious plan. Will likely downsize or expire. |

Source: Author’s compilation based on ITU filings and data from J. McDowell, planet4589.org.36 The list is not exhaustive.

The whole system, coupled with the present reality, creates a ‘Back of the Line’ problem. A new entrant must coordinate with every single valid filing that came before it. That means a new developing nation or startup trying to launch a standard internet satellite would need to technically coordinate its signals with hundreds of thousands of real and imaginary satellites. They are forced to overflow into technological wildernesses like the Q and V bands. These ‘lanes’ offer more bandwidth but suffer from higher rain fade. As a result, they require significantly more expensive and complex hardware to operate reliably.

Even a US-based, trillion-dollar company like Amazon was confronted with the ‘Back of the Line’ problem.37 Owing to the fact that they arrived late, they are legally subordinate to Starlink and even Cinnamon and Semaphore in the prime Ka-band. It is forcing them to engineer solutions in the V-band. Other late-entrant US firms like Hughes also planned for V-band, but have stalled the project because of high engineering costs.38

| Senior Rights (Incumbents) | Junior Rights (Latecomers) | |

|---|---|---|

| Low Cost / Standard Tech (Ku/Ka Band) | Monopolies Prime resources, low competition, legally protected from interference. | Dead-Ends Latecomers try to file here but cannot coordinate with existing satellites. |

| High Cost / Frontier Tech (Q/V Band or beyond) | Expansions Incumbents move here only when they need extra capacity. | Overflows Latecomers are forced here. They face harder physics and higher costs. |

Source: Author’s creation.

As evident from the table, many other firms are optimising for Q and V bands and other niche applications. Recent regulatory recommendations by TRAI in 2024 advise that new satellite internet systems should explore Q and V bands (40 to 75 GHz), as the Ku and Ka bands are too congested. 39 Given the demand, even the Q/V band will likely saturate in a decade. With megaconstellations from the US (Kuiper), China (Qianfan/Honghu), and others all targeting it simultaneously, experts predict coordination bottlenecks in the V-band by the 2030s.40 Therefore, the problem of orbital and frequency resources does not end with the Ku/Ka bands.

TRAI is the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

Like the slowing of Moore’s law, if the demand for spectrum resources outpaces the techniques for more efficient utilisation, the world will be left with a limited orbital frequency pool in the LEO. Most of these resources will be cornered by a handful of countries. For now, most of the players are from the developed world. As developing countries and their startups enter the space sector, they will not be welcomed by an open domain full of possibilities. A lot of the doors are already shut, and more are shutting by the year. And importantly, these doors do not reopen. Active constellations hold their rights in perpetuity. The prime orbital slots occupied today are effectively removed from the global commons forever. This locks out future generations of the developing world from the low-orbit space around Earth.

Global Commons are resource domains that do not fall within the jurisdiction of any one country, and are accessible to all nations (e.g., the High Seas, Antarctica, Outer Space).

2.3. The Repercussions

Space as a domain holds immense opportunity for human progress. Like a river that allows a city to thrive on its banks, space is adjacent to every country and the benefits from the use of space are open to all. LEO is the first of the milestones in any country’s space aspirations. A barrier to entry at this stage is undesirable on multiple levels.

Crowded and inaccessible low orbits are bad for all of humanity. Uncontrolled megaconstellation growth could compromise the long-term usability of LEO for everyone, not just latecomers. The escalating risk will render parts of Earth-space unusable in case of disaster.

Even in the absence of risk or disaster, a concentration of the LEO resources in the hands of a few entities is a poor outcome. Incumbents like the US and China will also pay a price. Their firms will face weaker competitive pressure, fewer disruptive challengers from abroad, and slower technological learning at the frontier.

Weaponisation and technological coercion will deepen geopolitical fault lines. If access to LEO connectivity and services becomes a lever of state power, it will harden into coercion. Such coercion will extend from banks and chips to orbits and bandwidth. The systems that can connect the world could actually end up fragmenting it.

For middle space powers like India, the threat of space technology dependence and risk of denial will persist into a long-term reality. India will be forced to be a customer rather than an exporter of LEO services. The economic hit will be felt in terms of brain drain, job creation and foreign investments. Meaningful innovation from India must either migrate abroad or accept a subordinate role in foreign value chains.

Given the Chinese lead in the domain, the Indian military will have to reckon with a much larger threat of Chinese space technology having a direct impact on its future crises or conflicts with China and Pakistan. The resulting risks will gnaw away at some of the leverage critical to making independent foreign policy decisions.

A crisis or miscalculation in orbit through collisions, cyberattacks, or deliberate targeting could trigger cascading failures of communications and sensing systems that both India and its rivals now rely on. It can turn LEO from a shared security enabler into a shared vulnerability.

The world will lose all the benefits and fruits of progress if the issue is not dealt with responsibly.

3. Dealing with the Problem

In this section, I have listed a series of measures that can address the issues we have discussed so far. These measures are designed to prevent the ailment, rather than treat the symptoms. Therefore, I will not be discussing mitigation measures that alleviate the situation—like debris removal or space traffic management—in this paper. While that line of thinking holds merit, it will be explored in future works.

In this paper, I discuss broad measures that attempt to change the system, which enables the incentives and motivations for the entrenchment of Lower Earth Orbital resources. Variations, or combinations, of these ideas can be considered for further deliberation and implementation by the concerned individuals and institutions.

3.1. Charge Rent for Orbits

Establish a multilateral mechanism that charges a ‘rent’ for orbits to price in congestion and risk.

The core reason for orbital entrenchment to occur is the fact that the cost of an orbital slot in LEO is nearly zero. After the filing, the orbital ‘real estate’ is free. This encourages the ‘land grab’ mentality where able countries would want to launch as many satellites as possible, as quickly as possible, to enjoy the resources.

An Orbital Use Fee imposes a cost upon orbital ‘real estate’. It puts a price on the risk that every new satellite adds to the environment. This is a tax to price in elements of congestion and risk that are currently not included in the cost of doing business.

The fee would not be arbitrary. It would be calculated based on the orbital stress a satellite megaconstellation causes. It would include factors like altitude (crowded areas cost more), cross-sectional area (larger targets cost more), and manoeuvrability (nimble satellites pay less).

This price signal forces operators to balance the marginal revenue of an additional satellite against the marginal cost it imposes on the global commons. They would optimise for better orbital efficiency and de-orbit the old hardware.

Challenges

- The authority levying the fee cannot be the respective nation-states, as they would be unwilling to self-inflict this cost.

- Developing states will see it as an additional barrier to entry. This can be addressed by making sure parts of the collected fee compensate the non-users of Earth-space, to some extent.

- The idea of orbital fees will face strong industry pushback.

3.2. Plurilateral Agreements

Form plurilateral alliances that pool resources, markets and bargaining power to counter monopolies.

A successful space technology ecosystem requires continental resources and markets. To counter the monopolisation of LEO by single-nation megaconstellations, groups of nations can form plurilateral arrangements. The Outer Space Treaty prevents national appropriation. It does not prevent nations from pooling their rights to create shared, competitive resources.

Such groupings lead to greater political coordination levels in a domain that otherwise leans towards rivalry. They can aggregate their market demand and regulatory power to wield greater strength as customers, too. They can mandate that any foreign megaconstellation wanting to serve their populations must reciprocally accept their spectrum sharing protocols. This creates safe harbours for the members’ satellites. It breaks the ‘winner-takes-all’ dynamic of the current ITU system by forcing incumbents to coexist.

Challenges

- Space programmes are deeply political and often have competing interests. It is difficult to find consensus.

- The free rider problem will be rampant.

In the free rider problem, those who benefit from resources (like safe orbits) do not pay for them, leading to overuse and degradation of the shared resource.

3.3. Layered Open Architectures

Implement degrees of interoperability through standards.

Proprietary hardware serves as the foundation for monopolies. Presently, Starlink satellites only talk to other Starlink satellites and stations. Standardising Optical Inter-Satellite Links can enable other satellites to communicate with Starlink and vice versa. It commoditises the physical infrastructure layer. This drastically lowers the entry for startups and developing nations. It leads to specialisation and innovation at the service layer. The result will be a much more efficient use of the orbital resources.

The openness can be implemented in degrees. A layered model can define a minimum open core, while leaving room for proprietary innovation above it. For example, basic standards for discovery, safety messages, and emergency traffic coordination could be open and interoperable. Meanwhile, advanced routing algorithms and value-added services will remain proprietary. This preserves incentives for incumbents to innovate, while preventing them from fully enclosing the orbital commons behind closed systems.

Optical Inter-Satellite Links are lasers used by satellites to communicate data directly to one another in space, rather than bouncing signals back down to ground stations.

Read my first paper about this topic: Satellite Internet Explained

Challenges

- It removes some of the incentive to innovate and vertically integrate.

- Powerful states might be unwilling.

3.4. Strengthen the ITU to reopen orbital resources

Strengthen the ITU to grant time-bound orbital rights, instead of perpetual ones.

The ITU was designed for a world that did not realistically anticipate the scarcity of orbital resources. Technological progress and megaconstellations have left ITU, in its current form, ill-equipped to fulfil its mandate. It should be given the power to control the availability of the global space commons better.

It should hand out time-bound orbital rights, instead of perpetual ones. Today, once a filing is brought into use and maintained, incumbents can effectively hold prime orbital resources indefinitely by continuously replacing satellites. A reformed ITU could introduce sunset clauses.

Assignments can be granted for fixed terms. They could be multi-decadal (for e.g., 15–20 years). When a term ends, capacity periodically reverts to the global pool and is reopened to competitive re-allocation—with specific windows reserved for emerging and developing space actors.

This stops the orbital commons land grab. It preserves planning certainty for operators over a long horizon, but guarantees that no entity can lock up the most valuable resources for eternity.

The ITU could also make more decisions based on the sustainable use of space. It should be given the power to reject filings. It should also be empowered to suspend the senior rights of an operator in response to irresponsible behaviour.

Challenges

- It requires states to accept that what they currently treat as de facto permanent priority would become a long-term lease.

- Incumbent operators will argue that sunset clauses create regulatory risk and may reduce long-horizon investment, even if terms are multi-decadal.

- Mechanisms for enforcement or punishment—besides diplomatic pressure and sanctions—are limited, especially if major powers refuse to accept constraints on their freedom of action.

3.5. From Soft Guidelines to Hard Clubs

Establish ‘clubs’ where major powers commit to enforceable safety and sharing protocols.

Even with the ITU, the world relies on voluntary guidelines for safety in space.41 This is unsustainable. We need stronger governance frameworks than the Outer Space Treaty. However, a centralised political instrument or institution like ‘World Space Government’ is politically impossible. It is unlikely that most countries in the world can be convinced to sign a new treaty for space.

Instead, the major space powers today, like the US, China, India, Japan, and Russia, along with major corporations like SpaceX, can form a club. As members of the club, they could agree to follow or implement safety or efficiency mechanisms like certain automatic manoeuvring capabilities, de-orbiting deadlines, frequency sharing protocols, and information sharing for warnings. The group can even issue binding manoeuvre commands among members. Anyone who follows the rules can become member over time. The benefits, as well as the demands, of the club can proportionately increase as the regime matures.

This incentivises good behaviour, while market cues punish the rogue actions. For instance, non-members can be charged higher insurance premiums, and face higher financing costs because they are statistically riskier to operate alongside. The club model is also useful for building global consensus on important space-related issues from the ground up, in increments.

Challenges

- Being a very securitised sector, many states will be unwilling to implement protocols that require sharing sensitive operational data.

- It needs the leading powers on board. A club without the main megaconstellation operators will have limited influence.

Conclusion

The entrenchment of Low Earth Orbit is not an inevitability of technological progress, but a failure of politics and governance. A higher level of effectiveness in global space governance is not just in the interest of India and the developing world. Even the leading space powers like the US and China desire a stable and predictable orbital environment. The US and China, having deployed the most capital and assets into Earth-space, now possess the greatest vulnerability. Every nation is ‘space-adjacent’. Therefore, the barrier to disrupting the orbital environment is far lower than the cost of securing it. Upon reaching a sufficient threshold of war, any actor can inflict asymmetric damage that harms the great powers disproportionately, since they have more to lose.

There is, therefore, a demonstrable incentive to get all stakeholders to negotiate their way out of this quandary. Doing so will change the low-orbit space activities from a Zero-Sum race to a Positive-Sum environment.

Zero-sum and Positive-sum are Game Theory terms. Zero-sum means one actor’s gain is another’s loss (current state). Positive-sum means all actors can benefit simultaneously (proposed future state).

References

Footnotes

Edward Ludlow, Eric Johnson, Katie Roof, and Loren Grush, “SpaceX Said to Plan Offering with Valuation of $400 Billion,” Bloomberg, July 8, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-07-08/spacex-valuation-said-to-hit-around-400-billion-in-share-sale.↩︎

Starlink, “Status Update,” X.com, n.d., https://x.com/Starlink/status/1986168985453490449.↩︎

Jonathan McDowell, “Space Statistics,” Jonathan’s Space Pages, n.d., https://planet4589.org/space/stats/stats.html.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

United Nations, “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea,” December 10, 1982, https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.↩︎

Alison Klesman, “The Kármán Line: Where Does Space Begin?” Astronomy.com, n.d., https://www.astronomy.com/space-exploration/the-karman-line-where-does-space-begin/.↩︎

CollectSpace Members, “Where Does Space Begin?” CollectSpace.com, January 2001, https://www.collectspace.com/ubb/Forum31/HTML/000121.html.↩︎

Office of Technology Assessment, “Anti-satellite Technologies,” U.S. Congress, September 1985, https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Anti_missile_and_Anti_satellite_Technolo/VmHfAAAAMAAJ.↩︎

UNOOSA, “Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space,” United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, October 1967, https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html.↩︎

Reuters Staff, “Reusable Rockets: Who Has Achieved What So Far,” Reuters, December 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/science/reusable-rockets-who-has-achieved-what-so-far-2025-12-03/.↩︎

Jonathan McDowell, “Space Statistics,” Jonathan’s Space Pages, n.d., https://planet4589.org/space/stats/stats.html.↩︎

Aaron C. Boley and Michael Byers, “Satellite Mega-Constellations Create Risks in Low Earth Orbit, the Atmosphere and on Earth,” Cornell University, June 2022, https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.05345.↩︎

The Outer Space Institute, “One Million Paper Satellites,” The Outer Space Institute, n.d., https://www.outerspaceinstitute.ca/osisite/wp-content/uploads/One-million-paper-satellites-Accepted-Version-.pdf.↩︎

Harry Baker, “How Many Satellites Could Fit in Earth Orbit and How Many Do We Really Need?” LiveScience.com, n.d., https://www.livescience.com/space/space-exploration/how-many-satellites-could-fit-in-earth-orbit-and-how-many-do-we-really-need.↩︎

Jonathan McDowell, “Satellite Constellations (Conlist),” Jonathan’s Space Pages, n.d., https://planet4589.org/space/con/conlist.html.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

ITU Radiocommunication Sector, “Resolution 35,” International Telecommunication Union, n.d., https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-R/space/Pages/res35main.aspx.↩︎

Sarah Thiele, Skye R. Heiland, Aaron C. Boley, and Samantha M. Lawler, “An Orbital House of Cards: Frequent Megaconstellation Close Conjunctions,” arXiv, December 10, 2025, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2512.09643.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Mike Wall, “SpaceX Starlink Satellites Made 50,000 Collision-Avoidance Maneuvers,” Space.com, July 6, 2023, https://www.space.com/spacex-starlink-50000-collision-avoidance-maneuvers-space-safety.↩︎

SpaceX, “SpaceX Gen1 and Gen2 Status Report,” Technical Report, Space Exploration Technologies Corp., 2025.↩︎

Alan Boyle, “ESA Spacecraft Dodges Starlink Satellite; SpaceX Says ‘Bug’ Prevented Early Warning,” GeekWire, September 3, 2019, https://www.geekwire.com/2019/esa-shifts-spacecraft-avoid-starlink-satellite-spacex-reports-bug-collision-warning-system/.↩︎

William E. Parker and Richard Linares, “Satellite Drag Analysis During the May 2024 Gannon Geomagnetic Storm,” Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets 61, no. 5 (2024): 1412–16, https://doi.org/10.2514/1.A36164.↩︎

Hugh G. Lewis and Donald J. Kessler, “Critical Number of Spacecraft in Low Earth Orbit: A New Assessment of the Stability of the Orbital Debris Environment,” in Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Space Debris, ed. T. Flohrer, S. Lemmens, and F. Schmitz (Darmstadt, Germany: ESA Space Debris Office, 2025), https://conference.sdo.esoc.esa.int/proceedings/sdc9/paper/305/SDC9-paper305.pdf.↩︎

ITU, “ITU Home,” International Telecommunication Union, n.d., https://www.itu.int/en/Pages/default.aspx.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

ITU Staff, “Space Connect: The Rise of LEO Satellite Constellations,” International Telecommunication Union, February 2025, https://www.itu.int/hub/2025/02/space-connect-the-rise-of-leo-satellite-constellations/.↩︎

The Outer Space Institute, “One Million Paper Satellites,” The Outer Space Institute, n.d., https://outerspaceinstitute.ca/osisite/wp-content/uploads/One-million-paper-satellites-Accepted-Version-.pdf.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Jonathan McDowell, “Satellite Constellations (Conlist),” Jonathan’s Space Pages, n.d., https://planet4589.org/space/con/conlist.html.↩︎

ITU Radiocommunication Sector, “Resolution 35,” International Telecommunication Union, n.d., https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-R/space/Pages/res35main.aspx.↩︎

G.E. Peterson et al., “Collision Risk to Low Earth Orbit Satellites,” American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2008, https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/1.A35987.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Jonathan McDowell, “Satellite Constellations (Conlist),” Jonathan’s Space Pages, n.d., https://planet4589.org/space/con/conlist.html.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Federal Communications Commission, “Order and Authorization (DA-20-792A1),” U.S. Government, 2020, https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/DA-20-792A1.pdf.↩︎

G.E. Peterson et al., “Collision Risk to Low Earth Orbit Satellites,” American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2008, https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/1.A35987.↩︎

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, “Recommendations (09052025),” Government of India, May 9, 2025, https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/2025-05/Recommendtion_09052025.pdf.↩︎

Kratos Staff, “Crowded Spectrum Pushing SATCOM Operators Into Q/V Band,” Kratos Defense & Security Solutions, n.d., https://www.kratosspace.com/constellations/articles/crowded-spectrum-pushing-satcom-operators-into-q-v-band.↩︎

Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, “Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities of the COPUOS,” United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, 2021, https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/PromotingSpaceSustainability/Publication_Final_English_June2021.pdf.↩︎