The author is a research analyst for Pakistan Studies, Indo-Pacific Programme at the Takshashila Institution.

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Manoj Kewalramani, Ameya Naik, and Shambhavi Naik for their valuable feedback and guidance.

Executive Summary:

The China-Pakistan defence partnership rests on a series of agreements and military cooperation projects rather than a formal alliance. The foundation of this relationship is largely anchored in regional dynamics, including concerns around India’s regional role, Chinese concerns around terrorism, security threats to Chinese nationals and projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and Beijing’s broader global ambitions.

Beijing maintains its position as Pakistan’s primary defence supplier, and advances bilateral military cooperation through regular joint exercises and technology transfer. However, persistent gaps exist in operational doctrines and technological capabilities. These factors have limited the countries’ ability to achieve full operational interoperability. Furthermore, China and Pakistan have opted for strategic ambiguity rather than formalising a defence pact, likely reflecting Beijing’s policy preference of avoiding binding treaties. The China-Pakistan relationship is described as a “threshold alliance,” 1 which aims to share the burden of countering India’s military and regional influence.

This approach enables Islamabad to hedge its bets, managing its increasing reliance on Beijing while avoiding alienation of the US and Western financial institutions, which remain crucial to its economic stability. Ultimately, the China-Pakistan defence relationship can be understood as a dynamic, interest-driven alignment. It enhances Pakistan’s capabilities and provides China with strategic depth in the Indian subcontinent, but falls short of a fully-integrated military alliance.

1. Introduction

The military partnership between China and Pakistan has progressed into one of the most durable strategic partnerships for both states. For Beijing, Pakistan serves as a counterbalance to India, its key regional rival, while also providing a vital land corridor through the CPEC, linking western China to the Arabian Sea. The China-Pakistan ‘all-weather friendship’ remains well-documented; however, the May 2025 India-Pakistan clashes drew attention to the integrated nature of their militaries, thereby prompting a deeper assessment of their operational capabilities. This paper conducts such a comprehensive analysis, with a particular focus on the latter’s dependence on the former. In order to do so, it employs a comparative methodology and qualitative study, relying on open-source defence publications, official statements, and secondary academic research.

Interoperability lies at the heart of contemporary defence partnerships with states pursuing deeper procedural, doctrinal and technological linkages. NATO’s conceptualisation of interoperability, enabling joint operations without necessitating uniform military equipment, offers a reference framework for assessing defence integration among countries.1 Applying this theory to the China-Pakistan military relationship reveals insights into the depth of their partnership.

Amid concerns about both militaries’ increasing integration, this paper argues that prominent structural, doctrinal, and technological limitations prevent the two countries from achieving full military interoperability. Instead, the relationship is characterised by pronounced asymmetry, which inhibits combined warfighting abilities, regardless of arms transfer and joint exercises. The findings highlight that despite institutionalising cooperation through frequent joint drills, weapons development, and intelligence cooperation, defence ties remain short of full operational interoperability. Divergent doctrines, command systems, and strategic imperatives limit integration to tactical and industrial levels.

The rest of this document is structured in six sections. After a brief historical overview, the paper explores three pillars of China-Pakistan military collaboration, including joint exercises, defence technology and production, and intelligence and cybersecurity linkages. This is followed by assessments of artificial intelligence, weapons, energy, nuclear, and space cooperation. The final section analyses the geopolitical implications of this partnership and identifies structural hindrances restricting deeper integration.

2. Historical Context

The trajectory of China-Pakistan relations was forged amid Cold War bloc politics and further reinforced by shared geopolitical realities, particularly their mutual rivalry with India.

2.1 Pakistan’s Western Alignment and Early China Policy

This bilateral relationship dates back to 1950, when Pakistan, in a surprising move, became the first Muslim nation to recognise the People’s Republic of China (PRC), with formal diplomatic relations established in May 1951.2 At that time, China was pursuing a revolutionary communist agenda. Meanwhile, Pakistan, facing a perceived existential threat from India after the 1947 partition, sought security guarantees from the West, consequently joining the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in 1954 and the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) in 1955. These blocs were designed by the US to contain the spread of communism in Asia, thereby placing Pakistan in the anti-China camp.

In practice, while the Pakistani leadership was anti-communist in its larger domestic ideology, the threat of communism was seen as secondary to the Indian problem. This gap in threat perception created an opening for Beijing. The anti-communist rhetoric stood in sharp contrast to Pakistan’s pragmatic diplomacy toward China, thereby creating space for bilateral engagement.

The Chinese leadership, especially under Premier Zhou Enlai, reciprocated positively to Pakistan’s recognition by pursuing a cooperative diplomatic relationship. At the Bandung Conference in 1955, Pakistani Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra assured Zhou that the country’s membership in Western alliances was not an anti-China position.3 While receiving substantial military and economic aid from the US, Pakistan maintained open diplomatic channels with China through the 1950s. As India-China friction escalated in the late 1950s, the strategic calculus in Islamabad began to shift. The nascent proximity between the US and India during this period was another catalyst in pushing Pakistan closer to China. Overall, the geopolitical reality of a purportedly hostile India created a natural convergence of interests between China and Pakistan.

The geopolitical landscape drastically transformed in the early 1960s under the presidency of Field Marshal Ayub Khan (1958-1969). The catalyst was the Sino-Indian war of 1962. For Pakistan, Western military aid to India in this period was viewed as a betrayal of alliance commitments.4 In response, Pakistan accelerated its diplomatic outreach to Beijing. This culminated in a 1963 China-Pakistan Agreement, a document that formally established the boundary between China’s Xinjiang province and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.5

2.2 China as Pakistan’s Defense Supplier

For Pakistan, the reliability of China as a defence partner was tested by several conflicts with India, in 1965, 1971, and most recently in 2025. In the first two conflicts, the US-imposed an arms embargo on both sides. This move disproportionately affected Pakistan, which was entirely dependent on American military hardware at the time, as opposed to India, which relied on a more diversified supply chain. China stepped in with the transfer of military hardware, including F-6 fighters (a variant of the MiG-19) and Type-59 tanks. The 1971 war, which led to the vivisection of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh, further alienated Pakistan from the US. At the same time, with India enjoying robust diplomatic and military backing from the Soviet Union, formalised through the Indo-Soviet treaty of friendship in 1971, Pakistan found itself somewhat isolated. China provided strong diplomatic support to Pakistan at the UN and extended military aid. Eventually, Pakistan’s role as a via media between the US and China in the 1970s and the subsequent proximity between the three following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan created new opportunities for Islamabad.

Since the 1990s, China has been Pakistan’s primary supplier of military hardware, including aircraft, submarines, tanks, and missiles. For Pakistan, China has remained its most crucial defence partner since the end of the Cold War, with Beijing serving as the dominant supplier of conventional arms and providing cost-effective alternatives to Western and Russian jets. In 1999, China and Pakistan signed a landmark agreement to jointly produce the JF-17 fighter jet, a milestone for Pakistan’s defence industry. By 2010, the JF-17 fleet was officially inducted into the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), which also expanded China’s footprint in global arms exports.6

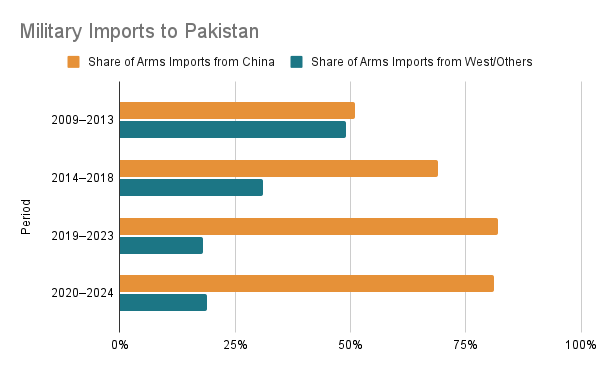

This partnership has driven a significant shift in Pakistan’s defence procurement patterns over the past three decades. In the early 1990s, Pakistan sourced a substantial portion of its military hardware from Western suppliers, with approximately 40 percent of its arms imports coming from the West and around 50 percent from China. This marked reduction in reliance on Western weaponry was also enabled by the former Trump administration’s 2018 decision to suspend most US security and military aid to Pakistan, citing concerns over Pakistan’s counterterrorism efforts. The suspension, which froze up to 1.3 billion USD in aid, led to a near halt in American defence exports to Pakistan and prompted Islamabad to shift its military acquisition from Beijing.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), between 2019 and 2023, 81% of Pakistan’s arms imports came from China, a sharp rise from 69% in the previous five-year period.7 This made Pakistan China’s largest arms buyer, accounting for nearly 61% of Chinese arms exports. This deep dependence has shifted the relationship from traditional military ties to one of pronounced asymmetry, where Pakistan’s defence capabilities are heavily reliant on Chinese technology and support.

Key acquisitions by Pakistan include J-10CE fighter jets, VT-4 battle tanks, Type 054A guided-missile frigates, and advanced missile defence systems, many of which involve technology transfer and local production, further embedding Chinese involvement in Pakistan’s military sector. China has further provided assistance in missile technology and co-development programmes, reinforcing Pakistan’s strategic deterrent capacity.

In the recent 2025 conflict between India and Pakistan, China reportedly supported its partner in three critical domains—combat hardware validation, real-time intelligence sharing, and information warfare.8 The conflict served as the combat debut for high-end Chinese systems, turning the war into a testing ground for China.

Pakistan deployed J-10C fighters equipped with PL-15 long-range air-to-air missiles. These systems were reportedly used to engage with Indian jets.9 Pakistan also used Chinese HQ-9 long-range surface-to-air missile systems.10 Additionally, China’s military also provided live inputs during the conflict, including China’s BeiDou Satellite Navigation System for positioning and targeting, which were independent of US-controlled GPS. High-resolution satellite imagery of Indian troop movement and airbase activity were also shared via fiber-optic links established under CPEC. Indigenous Link-17 datalink were also used, which were developed with Chinese assistance to receive data. Datalinks are communication systems that allow military platforms to exchange situational and sensor information in real-time.11 Developing an indigenous version remains crucial given it strengthens Pakistan’s ability to coordinate forces independently, while securing communication channels with Chinese counterparts.

The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission further reported the use of a wide disinformation campaign by Beijing, using fake social media accounts and AI-generated visuals of Rafale debris, with the intent to undermine the reputation of the French aircraft.12 This was intended to also bolster Pakistan’s procurement and strategic choices by promoting its own J-35 stealth fighter as an alternative.13

China’s dominance in Pakistan’s defence procurement has brought Beijing substantial strategic and economic benefits. The defence trade generates significant revenue for Chinese manufacturers, with arms export to Pakistan valued at over $5.28 billion between 2020-2024. Arming Pakistan also benefits China in creating a ‘two-front war’ threat for India. A militarily potent Pakistan forces New Delhi to split its resources and command focus between its western borders with Pakistan and eastern border with China.

2.3 Joint Military Exercises

Additionally, China’s strategic leverage is evident in joint military exercises, intelligence sharing, and the tailoring of advanced weapon systems specifically for Pakistan, such as the joint development of the JF-17 Thunder fighter aircraft and Hangor-class submarines. This deepening collaboration has made China effectively Pakistan’s only real ally in military matters, while providing Beijing with a secure access point to the Indian Ocean.

Regular joint military exercises such as Shaheen (Air Force), Sea Guardians (Naval), and Warrior (Army) drills further highlight the deepening military cooperation between China and Pakistan. Pakistan maintains a diversified portfolio of military exercises, although its engagements with other countries tend to be more specialised. The Ataturk series with Turkey is focused on special forces training, meanwhile the Al-Kassah exercises with Saudi Arabia emphasise counter-IED operations and mine clearance. Pakistan also hosts Western partners, including the US, through exercises such as Falcon Talon for the Air Force and Inspired Union for naval forces. However, concentrate on specific tactical competencies like counter-terrorism, in contrast to the multi-domain drills with China.

2.4 Economic Cooperation

The economic partnership between Pakistan and China began solidifying during Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s visit to Pakistan in May 2013. This was followed by the signing of the CPEC Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in July 2013. Launched formally in 2015, Phase-I of CPEC focused on energy and transport infrastructure projects.

Despite the boom in infrastructure, trade relations remain heavily skewed. The China-Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (CPFTA) led to a surge in Chinese imports. In FY 2023-2024, while Pakistan’s exports to China were valued at approximately $2.56 billion, imports from China stood at around $13-14 billion. The financial model, reliant on commercial loans, has exacerbated Pakistan’s sovereign debt crisis. Pakistan owes approximately $30 billion to China, leading to frequent calls for debt rollovers to prevent default.14

Recognising these disparities, the partnership has entered CPEC Phase II, formalised in the Action Plan 2025-2029.15 This phase shifts focus away from mega-infrastructure toward small projects in agriculture, mining, and B2B industrial cooperation to generate cash flow. This includes modernising Pakistan’s agrarian base and procuring mineral resources in Balochistan to cater to Chinese supply chains. Phase II also intends to boost geostrategic advantages for China, including access to Gwadar Port and the Indian Ocean, while relocating Chinese manufacturing to Pakistan through Special Economic Zones (SEZs). That said, a major prerequisite for Phase II is the protection of Chinese nationals operating in Pakistan, following militant attacks by Baloch and Islamist militants.

The economic cooperation under CPEC has further deepened Beijing’s strategic stakes in Pakistan’s internal and regional security environment. The economic partnership also expands to defence, intelligence, and military coordination beyond traditional arms transfers. As such, economic interdependence increasingly overlaps with strategic and military considerations.

3. Defining Military Interoperability

NATO defines interoperability as “the ability of different military organisations to conduct joint operations”.16 While NATO does not prescribe a linear ladder of interoperability, it frames the concept in terms of the degree to which allied forces can align and operate coherently at the tactical (unit-level missions), operational (joint campaigns, command-and-control and sustainment), and strategic levels (Alliance-wide objectives and integrated command). Interoperability is developed across functional domains, including command and control, doctrine, communications, training, logistics, and defence industrial standardisation.

This paper adopts the NATO approach as an analytical framework and uses it to assess the levels of integration in China–Pakistan military cooperation. It further explains that interoperability enables forces, units, and systems to function cohesively by requiring them to share common doctrine, procedures, infrastructure, and bases, as well as to communicate effectively. NATO also clarifies that “interoperability does not necessarily require common military equipment. What is important is that this equipment can share common facilities and is able to communicate with other equipment.”17

Besides doctrine and communication, interoperability also extends to military logistics, supply chains, and industrial-level cooperation. Allied nations that collaborate in the joint production of military equipment can develop an interoperable defence industrial base, enabling a maintenance capacity, an interchangeable supply of spare parts, and standardised operational procedures. This extent of integration limits coordination costs in joint planning, exercises, and potential joint combat.

While China and Pakistan have developed deep military ties, their interoperability remains limited when assessed against NATO standards.

4. Limitations of China-Pakistan Military Interoperability

Under the NATO framework, strategic-level synchronisation requires member states to have compatible command structures allowing for real-time alignment in pursuing national objectives. Despite the highly centralised nature of both militaries, China and Pakistan fall short of this compatibility due to fundamental differences in institutional oversight. The PLA operates through a top-down command system under the supervision of the Communist Party of China (CPC) via the Central Military Commission (CMC). Meanwhile, the Pakistani Army Chief has consolidated military authority into a personality-centric model. This process has been further institutionalised through the 27th Constitutional Amendment, which concentrates strategic and operational command under the Chief of Defence Forces (CDF).18 While this structure may speed up national-level decision-making, structural mismatch exists due to the divergent command culture, thereby impacting joint planning and strategic coordination.

Operational and tactical-level interoperability under NATO standards are dependent on platform compatibility, common technical protocols, weapon integration and standardised training. While Pakistan heavily relies on Chinese defence systems, it simultaneously operates Western-origin platforms, especially US-supplied F-16 fighter jets, thus creating interoperability constraints. Western systems, avionics, training standards operate on data protocols and structures that fundamentally differ from Chinese methods. The disparity in their inventory creates doctrinal and technological divides, thereby complicating interoperability.

Joint military exercises, such as the Shaheen and Sea Guardians, are more focused on upgrading coordination and operational familiarity rather than integration of forces. These drills enable both sides to prepare for combat scenarios, tactical maneuvers, and joint mission planning. As such, the scope of these exercises is mainly tactical, occurring at a unit level, as opposed to a higher strategic level of operations involving full-spectrum warfare across other military branches.

Beijing restricts access over the transfer of its advanced defence technologies, thus limiting access to systems including stealth capabilities, advanced electronic warfare platforms, and high-end command-and-control networks. Concurrently, bilateral data-sharing frameworks, required for operational-level interoperability under NATO standards, still remain comparatively underdeveloped. The combination of restricted technology sharing and limited information exchange indicates levels of interoperability.

Each of these points are discussed in detail below.

4.1 Command Structures and Operational Doctrines

China and Pakistan fundamentally differ in their military command structures, which limits true interoperability. The difference between party-led PLA and a personality-centric centralised command in Pakistan has complicated the foundation of a unified joint planning mechanism for interoperability.19

The Chinese CMC, a commanding body chaired by President Xi Jinping, directly controls a joint operations system that runs from the CMC down to five theatre commands—eastern, southern, western, northern, and central. These theater commands integrate the army, navy, air force, rocket force, and strategic support units under a single commander for operations, serving party-defined objectives.20 Meanwhile, Pakistan’s structure is more fragmented and multilayered, with the command structured in a centralised manner following the 27th Constitutional Amendment, which established the office of Chief of Defense Forces (CDF).21 This concentration of the operational and administrative authority under an Army-centric command replaces the previous consensus-based Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee.

At the institutional level, militaries of both countries retain distinct national command structures and maintain sovereign control over conflict-planning, nuclear decision-making, and theater-level operations, even with expanded mechanisms for consultations and coordination.22 In terms of operations, frequent joint drills are nudging both militaries toward a limited convergence of doctrine in conventional domains. This further allows Pakistan’s military to adapt to Chinese concepts of integrated joint operations and network-centric warfare. Meanwhile, China has the opportunity to incorporate lessons from Pakistan’s experience in counter-militancy operations, border management, and high-altitude operations. Nevertheless, a critical barrier to proper interoperability is the incompatibility of command and control networks. However, it falls short of the deeply institutionalised interoperability seen in alliances like NATO.

4.2 Pakistan’s Western Equipment

The defence partnership between China and Pakistan includes joint development of weapons systems and limited technology transfer. However, operational integration has faced hurdles due to Pakistan’s hybrid arsenal. These platforms like F-16 Fighting Falcon and the Sweden-made Saab 2000 Erieye AEW&C operate on Western data links (such as Link 16) and avionics standards that are technically incompatible with Chinese protocols.

Link 16 is a military communications network used by US, NATO, and allied forces to exchange real-time tactical data. It allows aircraft, naval vessels, ground forces, and command centers to automatically share location data, threat identification, and targeting information.

Logistics, sustainment, and training remain another constraint. Western-origin jets require independent supply chains, maintenance tools, and training distinct from Chinese hardware. The use of Western equipment also adds political limitations to Pakistan that cut against deep operational collaboration with China. Pakistan’s access to upgrades, software patches, and munition for Western systems depends on maintaining ties with those suppliers, who would grow wary should they be used in operations alongside the PLA. All these factors, particularly the disparity in doctrinal and technical divide, limits the ability of Chinese and Pakistani assets to share real-time data in war-time situations. Western suppliers could grow wary given the risk of technology leakage and exposure to the PLA.

That said, efforts to mitigate these challenges are centered on the JF-17 Thunder, which remains crucial to the countries’ interoperability. The Block III variant features avionics, radar systems, and displays to deploy Chinese-origin missiles 23. However, operational integration has not been fully achieved. China is also modernising Pakistan’s navy, including the provision of Hangor-class submarines. Pakistan’s inability to access high-end stealth and electronic warfare networks limits partnership to acquisition rather than system collaboration. This restriction is considering China’s policy of reserving sensitive stealth source codes for its military given similar anxieties of technology leakage through Pakistan’s defence ties with the West.

4.3 Joint Military Exercises

This section discusses the Shaheen, Sea Guardians, and Warrior series, which are among the major joint military exercises conducted by China and Pakistan. Separately, both militaries also participate in exercises like Aman, a Pakistan-hosted multinational naval drill, and counter-terror joint drill Youyi (Friendship) Exercises. The latter involves special forces training for urban and mountainous warfare.

4.3.1. Sea Guardian The Sea Guardian drills have progressed in complexity, scale, and naval hardware deployment since the inaugural exercise in 2020. The first exercise focused on foundational joint operations, including search and rescue, anti-submarine warfare, and live-fire exercises. This expanded to include drills such as joint strikes against maritime targets, joint tactical maneuvering, and joint support for damaged vessels in Sea Guardians-2. The third edition of the Sea Guardians, held in 2023, introduced elements of joint maritime patrol (a first for these two Navies), a shore-based phase, personnel swapping from each naval force, and combined arms operations integrating ships, submarines, and air assets. The exercises held thus far have been irregularly spaced. In February 2025, Pakistan hosted the multinational exercise Aman, in which the Chinese PLA Navy (PLAN) was a major participant. No Sea Guardian drill was held in 2025.

These drills form an important element of China’s broader maritime strategy. They serve as a regularised avenue for the PLAN to strengthen cooperation, build operational experience, and signal continued engagement in the Indian Ocean. These exercises boost the PLAN’s operational access to the Arabian Sea, beef-up military cooperation with a crucial partner, and counterbalance India’s naval presence in the region.

The Pakistan Navy’s current operational focus and economic limitations mean it is likely to primarily remain a ‘green-water’ force in the near future, oriented toward coastal defence and regional sea denial rather than global power projection. However, Pakistani naval officials have expressed aspirations to develop blue-water capabilities over the long term. In October 2025, Admiral Naveed Ashraf, Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS) of Pakistan Navy stated ambitions to evolve into a “credible Blue Water force” by inducting modern surface and subsurface platforms, augmenting naval aviation and special operations forces, investing in maritime domain awareness, boosting indigenous shipbuilding and technological capabilities, and continuing regional cooperation and multinational missions. 24 The present constraints in resources, infrastructure, technology, and economy will diminish Pakistan’s ability to acquire blue-water status in the near future. That said, the ongoing naval modernisation-enabled by Chinese support will likely lay the ground for more ambitious maritime projects in the coming years.

A green water force is a maritime power capable of operating in its nation’s littoral (coastal) zones and surrounding regional seas, however it lacks the logistical sustainment required for long-range, global power projection. It sits between a “brown water” navy, which is limited to rivers and immediate shorelines, and a “blue water” navy, which can operate across deep oceans worldwide.

4.3.2 Shaheen The Shaheen series of joint air exercises between the PAF and the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) has grown in significance since its inception in 2011. The exercises have progressed from basic maneuvers to sophisticated scenarios that enhance interoperability, aerial combat skills, and mutual familiarity with operational strategies. Such exercises serve as a platform to test joint aerial operations, including beyond-visual-range (BVR) combat, electronic warfare, and high-altitude missions-capabilities crucial for operations in challenging terrain like the Himalayas.

While some exercises have featured Chinese Sukhoi Su-27 and Su-30MKK aircraft, offering Pakistan exposure to platforms with structural similarities to the Indian Air Force’s (IAF) SU-30MKI, the operational insights gained are likely to be limited.25 The Indian SU-30MKI is extensively customised with Israeli electronic warfare systems, French and Indian avionics, and indigenous DRDO Astra missiles, whereas the Chinese MKK relies primarily on Russian technology. As a result, the substantial differences in mission systems and combat capabilities can only partially translate to Pakistan’s understanding of the Indian SU-30MKI’s operational profile. Future Shaheen exercises may provide the PAF with exposure to China’s fifth-generation fighters such as the J-20 and FC-31, enabling Pakistan to assess its own needs for potential future procurement.26 Meanwhile, China benefits from the PAF’s experience in ambush tactics and countermeasures developed to counter the IAF’s doctrine, thereby deepening the strategic value of these joint drills.

This exposure, combined with Pakistan’s growing reliance on Chinese air power, further deepens China-Pakistani military cooperation and aligns Pakistan’s aerial warfare strategies more closely with Chinese doctrine. Platforms such as JF-17 require Pakistani pilots and technicians to assume Chinese operational procedures, and maintenance standards. Participation in the Shaheen series has exposed PAF to PLA Air Force concepts, such as integrated air-defence coordination, electronic warfare, and air-to-surface strike operations. The frequency of these drills will further cement knowledge exchange, including Pakistan’s experience in countering Indian air strategies.

However, the increasing dependence of PAF on Chinese aircraft presents the risk of over-reliance on Beijing, limiting Pakistan’s autonomy and flexibility in defence procurement. There are also questions around Beijing’s ability to fulfill Pakistan’s requirements in a scenario in which China goes to war in the Taiwan Strait.

4.3.3. Warrior Series Finally, the Warrior series of joint military exercises between China and Pakistan essentially focuses on special operations forces (SOF) training, counter-terrorism, and unconventional warfare tactics. These exercises are designed to improve interoperability between the PLA’s Ground Force (PLAGF) and the Pakistan Army’s Special Services Group (SSG).27 Pakistan’s experience in counter-insurgency operations in the provinces of Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa further benefits Chinese forces with inputs on asymmetric warfare, urban combat, and counter-militancy strategies.

Similar to naval and aerial exercises, the Warrior exercises, initiated in 2006, have evolved in complexity, integrating night-time operations, close-quarters battle, and high-altitude warfare training. The inclusion of advanced weapons and specialised counter-militancy drills provides a focus on preparing for counter-insurgency missions and hostage rescue situations. For China, participating in these exercises serves to improve the PLAGF Special Operations Forces’ ability to operate in Himalayan terrains, and provides access to Pakistan’s doctrinal approaches to irregular warfare.

Meanwhile, the exercises allow Pakistan to evaluate Chinese tactical gear, small arms, and surveillance systems. This is advantageous for Pakistan as its military is modernising the special operations forces with new night vision systems, unmanned aerial vehicles, and other warfare capabilities. The frequency of Warrior exercises also informs China’s deepening involvement in Pakistan’s security apparatus. The exercises also align with Beijing’s interests in securing the CPEC projects, which are threatened by Baloch insurgent groups and Islamist factions such as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

| Edition | Year | Location | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warrior-I | 2013 | Pakistan | Inaugural Exercise |

| Warrior-II | 2014 | China | |

| Warrior-III | 2015 | Pakistan | |

| Warrior-IV | 2016 | China | |

| Warrior-V | 2018 | Pakistan | |

| Warrior-VI | 2019 | China | |

| No Exercise | 2020-2022 | - | Gap due to COVID |

| Warrior-VII | 2023 | - | Postponed and cancelled |

| Warrior- VIII | 2024 | Pakistan |

Table summarising the frequency and timeline of the China-Pakistan “Warrior” joint military exercises

Defence Technology and Production

The foundation of the China-Pakistan defence partnership is rooted in joint development of military hardware, technology transfer, and strategic cooperation across multiple domains. The JF-17 Thunder is the flagship of this collaboration, representing a fourth-generation combat aircraft, and remains a hallmark of China-Pakistan collaboration. Initiated in the 1990s, the aircraft achieved its maiden flight in 2003. 28 It was inducted into the PAF in 2007. The JF-17, since then, has undergone sustained upgrades, most notably the Block III variant, which incorporates advanced avionics, a fly-by-wire system, and strengthened electronic warfare capabilities.

While this variant has been publicised as capable of deploying Chinese-origin munition, including PL-15E long-range air-to-air missile and PL-10E high-off-boresight missile, there are apprehensions surrounding the full operational integration of these systems.29 Most importantly, these capabilities remain unproven in operational settings. More broadly, integrating new sensors, communication suites, or electronic-warfare packages continues to be a challenge as a result of software inconsistencies, restrictions in data-fusion performance, and misalignment of the jet’s architecture.

Separately, Pakistan also received the HQ-9 and HQ-16 surface-to-air missile systems from China. 30 The HQ-9 offers long-range interception and the HQ-16 provides medium-range defence, thereby building up Pakistan’s air defence capabilities. However, both systems were reportedly challenged by India’s multi-layered air-defence systems. Assessments indicate Pakistan’s struggle with saturation attacks and electronic countermeasures, thus indicating operational limitations.

China is also modernising Pakistan’s surface and sub-surface fleet by building several advanced naval warships. This includes a deal for four Type 054A/P guided-missile frigates, which were commissioned and delivered between 2021-2023. 31 Pakistan is further acquiring eight Hangor-class submarines. Three of these submarines have been delivered. The fourth has been launched in December 2025, while the remaining four are slated to be assembled in Pakistan with a delivery timeline of 2028. 32 China reportedly handed over the third of eight new Hangor-class submarines to Pakistan in August 2025. 33

Intelligence Sharing and Cybersecurity

Sino-Pakistani intelligence and cybersecurity cooperation evolved from a limited focus on threats targeting CPEC projects to a structured, agency-to-agency collaboration.34 Historically, the focus of the partnership between Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) was concentrated to monitor militant groups in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s border regions since the 1980s, which tightened after CPEC projects took off.35 Over time, this cooperation has now broadened its scope to cover joint analysis of threats, early-warning mechanisms, and coordination on counter-insurgency operations, including against shared regional adversaries. It involves shared assessments on Indian troop movements, political stability in the Taliban-administered Kabul, and dissent in the Indian subcontinent. The collaboration has also extended to evolving a shared threat perception of the region and aligned security requirements.36

China has also strengthened Pakistan’s space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, especially through its support for the Pakistan Remote Sensing Satellite-1 (PRSS-1). This operates tracking, telemetry, and command stations in Pakistan, enabling satellite and missile monitoring. These measures have equipped Pakistan to track Indian satellite launches, monitor troop movement, and receive early warnings of missile tests. The operational effectiveness of these intelligence systems were tested during the May 2025 India-Pakistan conflict with China-provided ISR and UAV assets offering situational awareness 37. However, shortfalls in real-time intelligence processing and integration show limitations of interoperability. Unlike alliances, such as NATO or the Five Eyes, there are no fully-integrated analytic centers or routine real-time data sharing mechanisms between China and Pakistan.

At present, intelligence cooperation is concentrated in strategic monitoring of India, and protecting CPEC assets. Pakistan has further acquired encrypted communications and GPS devices, along with UAVs like the CH-4 and Wing Loong II. 38 Nevertheless, there is no evidence of deeply integrated intelligence systems, joint analytical centers, or routine real-time intelligence mechanisms. While this highlights deepening intelligence ties, they remain short of being institutionalised, real-time, and multi-domain.

4.4 Nuclear and Missile Cooperation

The instrumental role of China in Pakistan’s nuclear program remains a consequential factor in their bilateral relationship. Historically, in the 1980s and 1990s, China provided critical elements for the building of Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities, including the transfer of a warhead design, highly enriched uranium, and thousands of ring magnets needed for gas centrifuges. 39 China also offered direct technical support for constructing the Khushab plutonium production reactor, a facility integral in Pakistan’s transition from simple uranium bombs to lighter, more compact plutonium warheads suitable for missile delivery.39 This military assistance was covert, designed to counterbalance India’s stacking arsenal, unlike the overt cooperation at the Chashma Nuclear Power Plants for civilian energy production. Nevertheless, publicly available information appears to indicate that nuclear cooperation has not advanced beyond this phase. The command and control of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal now remains under the command of the CDS, guarded against external influence, including from China.

This separation of operations aligns with China’s official narrative, which publicly emphasises its commitments to non-proliferation. Strategically, China offers diplomatic cover for Pakistan, often linking Pakistan’s status with India’s in forums such as the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). For Beijing, Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities remain an independent deterrent that serves China’s interests by balancing India.

4.5 Emerging Technologies and Space

The China-Pakistan strategic partnership has expanded significantly in artificial intelligence (AI), UAVs, and space collaboration. The establishment of the China-Pakistan Intelligent Systems (CPInS) Lab at National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) in 2022, in partnership with the Guangzhou Institute of Software Application Technology, focuses on advancing UAV control systems and AI-driven recognition and localisation.40 Pakistan also launched its own initiatives, such as the Centre for Artificial Intelligence and Computing and the Army Centre of Emerging Technologies, with the aim to build defence and cybersecurity capabilities.

Separately, China is a major supplier of UAVs to Pakistan, notably providing export variants like the CH-4 armed drone. These UAVs have contributed in enhancing Pakistan’s surveillance and strike capabilities, especially in counterterrorism and border security operations.41 Some Chinese-made UAVs were also recovered by Indian security forces on border states with Pakistan including Punjab, Rajasthan, and Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). While most Chinese-supplied UAVs are remotely piloted rather than fully autonomous, their integration requires advanced remote pilot training. Reports indicate that Chinese trainers have played a role in instructing Pakistani personnel on UAV operations, though the extent of this involvement is not fully public. Reports of potential co-production of UAVs in Pakistan have also emerged.

In May 2024, China launched Pakistan’s Multi-Mission Communications Satellite (MM1), marking the third whole-satellite project between the China Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC) and Pakistan, following Paksat-1R and PRSS-1.42 While MM1 is primarily designed for civilian communication purposes, its advanced capabilities could also support military operations by providing sophisticated infrastructure. That said, there is no public information indicating that MM1 facilitates real-time data sharing for military operations between both countries.

Overall, China has been instrumental in enhancing Pakistan’s space capabilities, facilitating the launch of satellites that augment reconnaissance and communication infrastructures. This collaboration strengthens Pakistan’s strategic assets while also integrating its system more closely with China’s space initiatives. Pakistan’s military navigation and targeting systems reportedly rely on China’s BeiDou satellite navigation network, marking a significant step toward operational independence from Western systems.43 This integration spans a range of platforms, from UAVs and fighter jets like the JF-17 to missile guidance systems and naval assets. These developments make space and satellite navigation one of the few domains where China and Pakistan have achieved close, practical military interoperability.

5. Challenges and Considerations

China-Pakistan ties, despite underlying reservations from both sides, have drawn significant scrutiny from regional stakeholders, particularly India and the US. This relationship is marked by a consistent trajectory of defence collaboration that is reshaping the strategic landscape in the subcontinent.

The deepening military cooperation between China and Pakistan should compel India to reassess its defence calculus and resource allocation in light of a plausible two-front conflict scenario. Pakistan’s growing reliance on Chinese military support, including advanced weaponry, submarines, and fighter jets, significantly enhances its capabilities, posing increased strategic challenges for India.

While interoperability between their militaries may be overstated, the trajectory of China-Pakistan defence collaboration has significant geopolitical implications, particularly for India. That said, the influential Pakistan military apparatus will aim to prevent any fallout with the US, given their defence necessities, and is likely to maintain a balanced stance amid great power rivalries. Despite Pakistan’s increasing reliance on Chinese military hardware, its defence apparatus heavily relies on key imports and collaborations with the US and Western countries, most notably for maintenance and upgrades of its F-16 fighter fleet, specialised arms and ammunition, and access to advanced dual-use technologies. This is especially pertinent considering Pakistan’s heavy reliance on international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Western markets for its economic stability.

Islamabad’s strategic balancing act, cautiously avoiding being pigeonholed with any anti-Western bloc led by China or Russia, is thus likely to continue. This might include a diversified approach—relying on Chinese support for defence procurement while trusting Western technology like F-16 aircraft and supporting systems for operational credibility. Ultimately, Pakistan will offer privileged access and influence to multiple patrons, while avoiding full alignment with a single bloc.

For China, deepening military and economic relations with Pakistan is accompanied by apprehensions over Islamabad’s diversification of partnerships, with the latter seeking to remain Western-aligned. The current momentum in US-Pakistan ties, and the publicly declared defense partnership between Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, challenge Beijing’s hope for exclusive influence. As such, China is likely to remain wary of Americans gaining insight into Chinese military technology supplied to Pakistan, especially considering new defense arrangements are crafted through broader ties with Saudi Arabia and the US.

This document argues that while the partnership between China and Pakistan military institutions is robust and strategically relevant, the extent of interoperability is still fairly limited. Both countries often use terms such as ‘coordination’, ‘cooperation’, and ‘jointness’ to describe their engagements. However, they signify varying levels of collaboration rather than full integration. The practical challenges, including differences in military doctrine, communication systems, operational frameworks, and economic leverage, limit the full actualisation of interoperability.

Additionally, Pakistan’s economic constraints will continue to impede its ability to fully capitalise on technological transfers and defence collaborations with China, and to enhance domestic defence manufacturing capabilities. Collectively, these factors imply that while the partnership is advancing at a tactical level, operationally, it remains constrained by asymmetric command structures, technology restrictions, and differing strategic imperatives.

Footnotes

North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Interoperability for Joint Operations. Brussels: NATO Public Diplomacy Division, 2012. Link↩︎

“China and Pakistan,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, accessed December 9, 2025. Link↩︎

Ghulam Ali, China-Pakistan Relations: A Historical Analysis (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2017), 54–58.↩︎

Khan, Mohammad Ayub. Friends Not Masters: A Political Autobiography. London: Oxford University Press, 1967.↩︎

“The Boundary Agreement Between China and Pakistan, 1963,” United Nations Treaty Collection, Treaty Series vol. 486, no. 7051.↩︎

“JF-17 Thunder: A Game Changer,” Pakistan Aeronautical Complex Kamra, accessed December 9, 2025 Link↩︎

Pieter D. Wezeman et al., “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023,” SIPRI Fact Sheet, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2024, 2–6.↩︎

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), “Chapter 6: Asia,” in The Military Balance 2025 (London: Routledge, 2025), 290–295.↩︎

Pakistan Formally Inducts J-10C Fighters into Air Force,” Al Jazeera, March 11, 2022, Link↩︎

International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), The Military Balance 2024 (London: Routledge, 2024), 301-303.↩︎

Sameer Hashmi, “Modernizing the Skies: The Evolution of Pakistan’s Tactical Data Links,” Strategic Studies Quarterly 15, no. 2 (Summer 2021): 50.↩︎

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2025 Annual Report to Congress (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2025)↩︎

Defence Star, “Pakistan’s Reported Acquisition of China’s J-35 Stealth Fighters: Implications for India’s Strategic Options,” December 28, 2024, Link↩︎

International Monetary Fund. “Pakistan: 2024 Article IV Consultation and Review Under the Stand-By Arrangement.” Washington, D.C.: IMF, 2024. Link↩︎

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. “Joint Statement between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan on the Realization of CPEC Phase II.” June 8, 2025. Link↩︎

NATO, “Interoperability: Connecting NATO Forces,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, last modified March 24, 2023, Link↩︎

North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Interoperability: Connecting NATO Forces. Brussels: NATO HQ, 2025. Link↩︎

Government of Pakistan. The Constitution (Twenty-Seventh Amendment) Act, 2025. Islamabad: Gazette of Pakistan, 2025.↩︎

Stanzel, Angela. The Transformation of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army into a ‘World-class Military’. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2025. Link↩︎

National Assembly of Pakistan. Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Armed Forces (Part XII, Chapter 2). Islamabad: National Assembly of Pakistan, 2025.↩︎

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. SIPRI Yearbook 2025: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025.↩︎

Lalwani, Sameer. A Threshold Alliance: The China-Pakistan Military Relationship. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 2023. Link↩︎

Liu, Xuanzun. Upgraded JF-17 Block 3 Fighter Jet Features World-Class Systems. Beijing: Global Times, 2024.↩︎

Vavasseur, Xavier. Pakistan Navy Commissions PMS Tughril Type 054A/P Frigate. Paris: Naval News, 2022.↩︎

China Military Online. “China-Pakistan Joint Air Force Exercise Shaheen-IX Concludes.” Beijing: China Military Online, December 26, 2020. Link↩︎

Ansari, Usman. Pakistan Air Force Announces Plans to Acquire Chinese FC-31 Stealth Fighters. Tysons: Defense News, 2024.↩︎

Inter Services Public Relations. Joint Exercise Warrior-VIII: Strengthening Counter-Terrorism Cooperation. Rawalpindi: ISPR, 2024.↩︎

Airforce Technology. JF-17 Thunder Multirole Fighter Aircraft. London: Verdict Media Limited, 2023.↩︎

Bronk, Justin. Russian and Chinese Combat Air Trends. London: Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), 2022.↩︎

Global Security. Pakistan Army Inducts HQ-9/P High-to-Medium Air Defence System. Alexandria: GlobalSecurity.org, 2025.↩︎

Liu, Xuanzun. “Exclusive: China delivers two Type 054A/P frigates to the Pakistan Navy, wraps up four-ship deal.” Global Times, May 10, 2023. Link↩︎

Naval News Staff. “Pakistan Navy Launches 4th Hangor-class Submarine ‘Ghazi’ in China.” Naval News, December 17, 2025. Link↩︎

Radio Pakistan. “Pakistan Navy launches 3rd Hangor Class Submarine Mangro.” Islamabad: Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation, August 15, 2025. Link↩︎

Small, Andrew. The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.↩︎

Lalwani, Sameer. China’s Military Basing and Logistics in the Indian Ocean. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023. Link↩︎

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. China’s Strategic Support to Pakistan’s Missile Programme. Solna: SIPRI Commentary, 2023.Link↩︎

The Print. Pakistan Deploys Chinese-made Combat Drones near LoC. New Delhi: The Print, 2022. Link↩︎

The European Times. “China’s technology aids terrorism in Kashmir.” European Times, August 10, 2025. Link↩︎

Smith, R. Jeffrey, and Joby Warrick. “A Nuclear Power’s Act of Proliferation.” Washington Post, November 13, 2009. Link↩︎

Business Recorder. “‘Pakistan is capable of becoming AI development hub in South Asia’ - Dr. Wu Jun.” February 12, 2024. Link↩︎

New America. “World of Drones: Who Has What?.” Washington, D.C.: New America, 2025. Link↩︎

Dawn. “Pakistan’s Multi-mission Satellite PakSat-MM1 Launched from China.” Dawn, May 30, 2024. Link↩︎

Pakistan Today. “Pakistan Outlines Six-Point Roadmap to Harness BeiDou for Growth.” Profit by Pakistan Today, September 24, 2025. Link↩︎