EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper critically examines the evolving concept of the ‘Grey Zone’ in conflict dynamics, contextualising its impact on India’s security challenges. It is approached as an operational space,contrary to warfare. The Grey Zone is best understood as an overarching operational space between peace and open war, where state and non-state actors employ coercive methods across multiple domains (physical and cognitive) to advance geopolitical objectives below the threshold of overt conflict.

The author is a researcher working with the Defence Fellowship Programme at the Takshashila Institution.

Key Concepts and Models

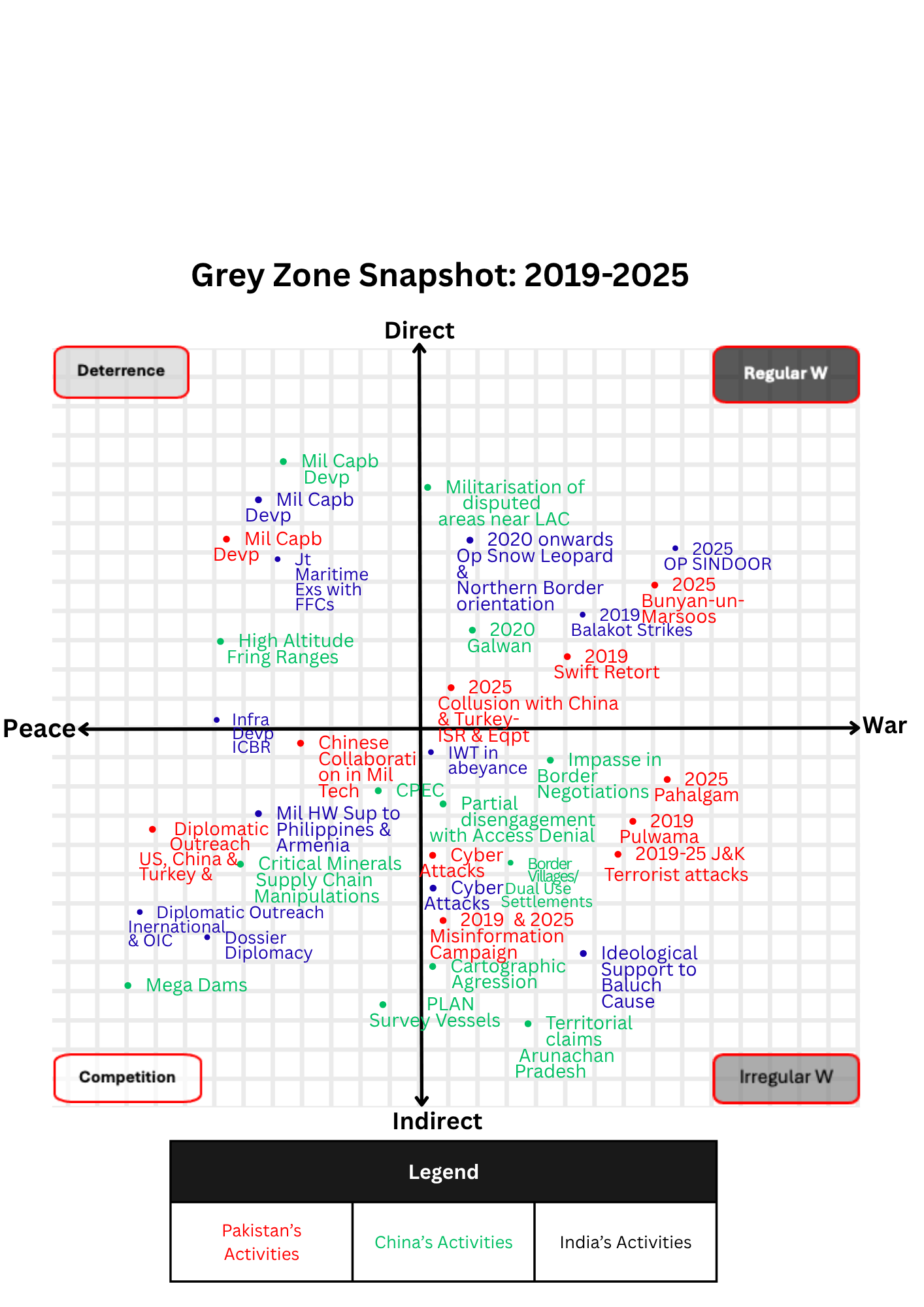

This paper maps Grey Zone activities across a four-quadrant conflict model for analytical clarity: regular warfare, irregular warfare, competition, and deterrence.

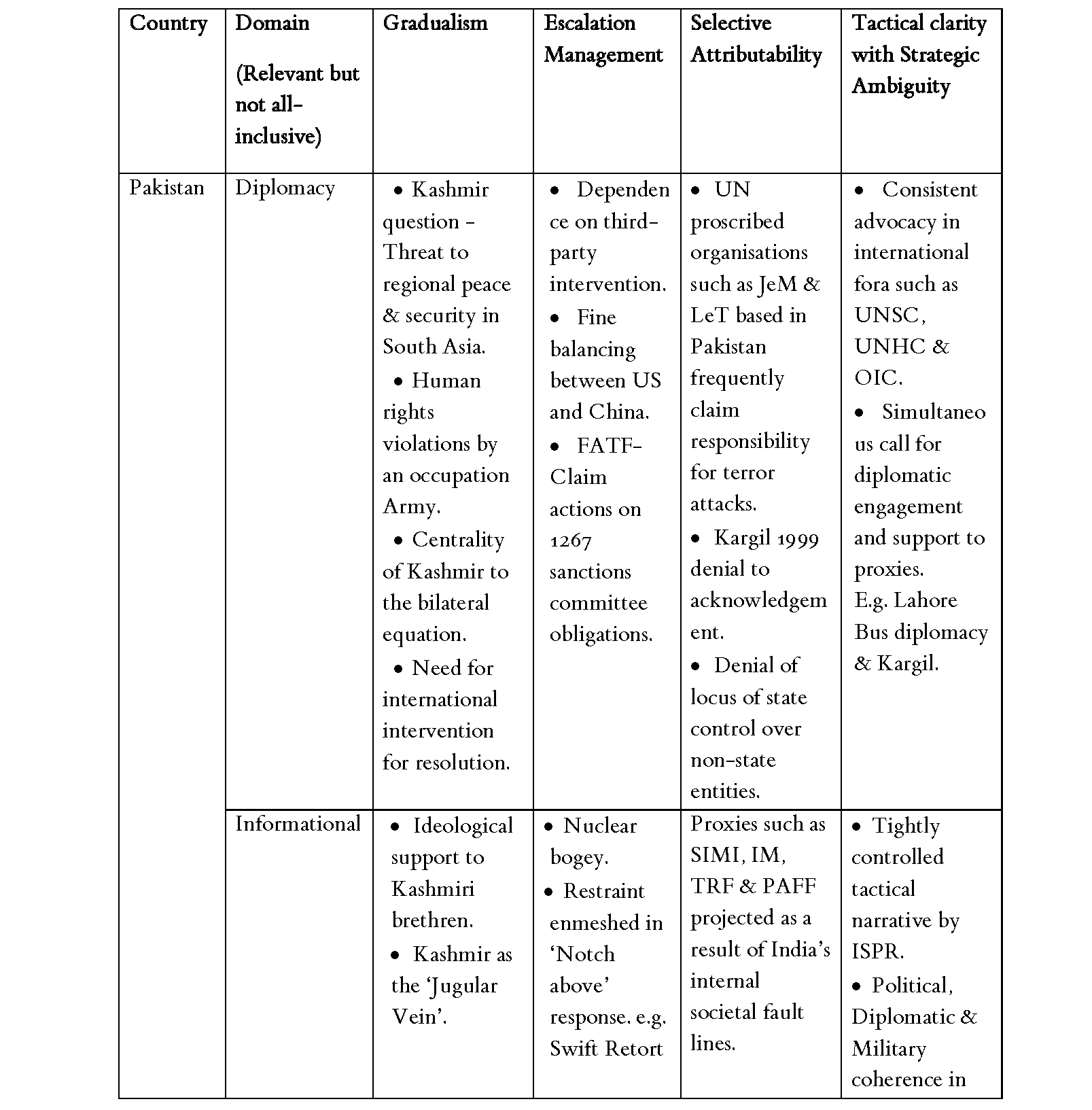

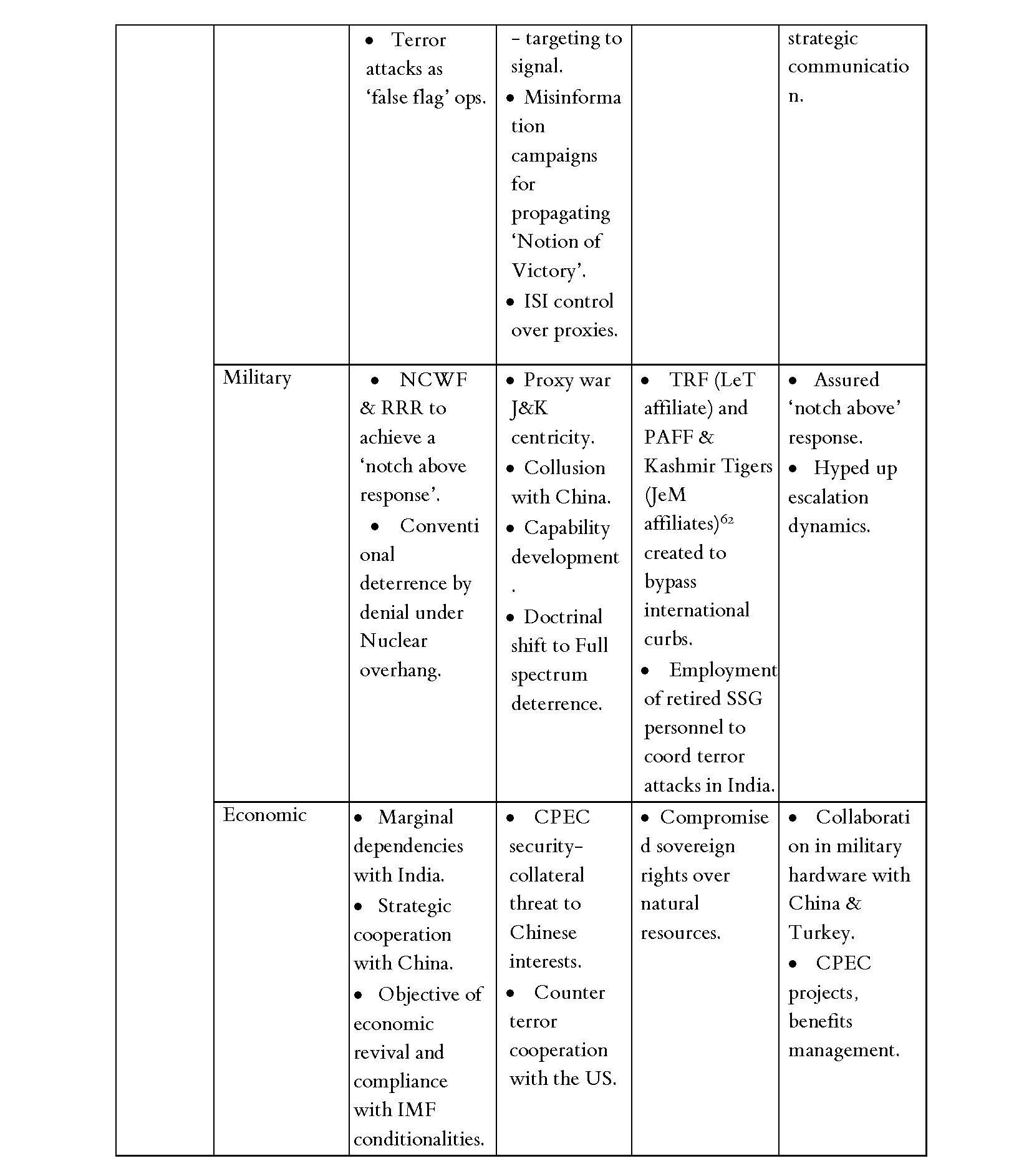

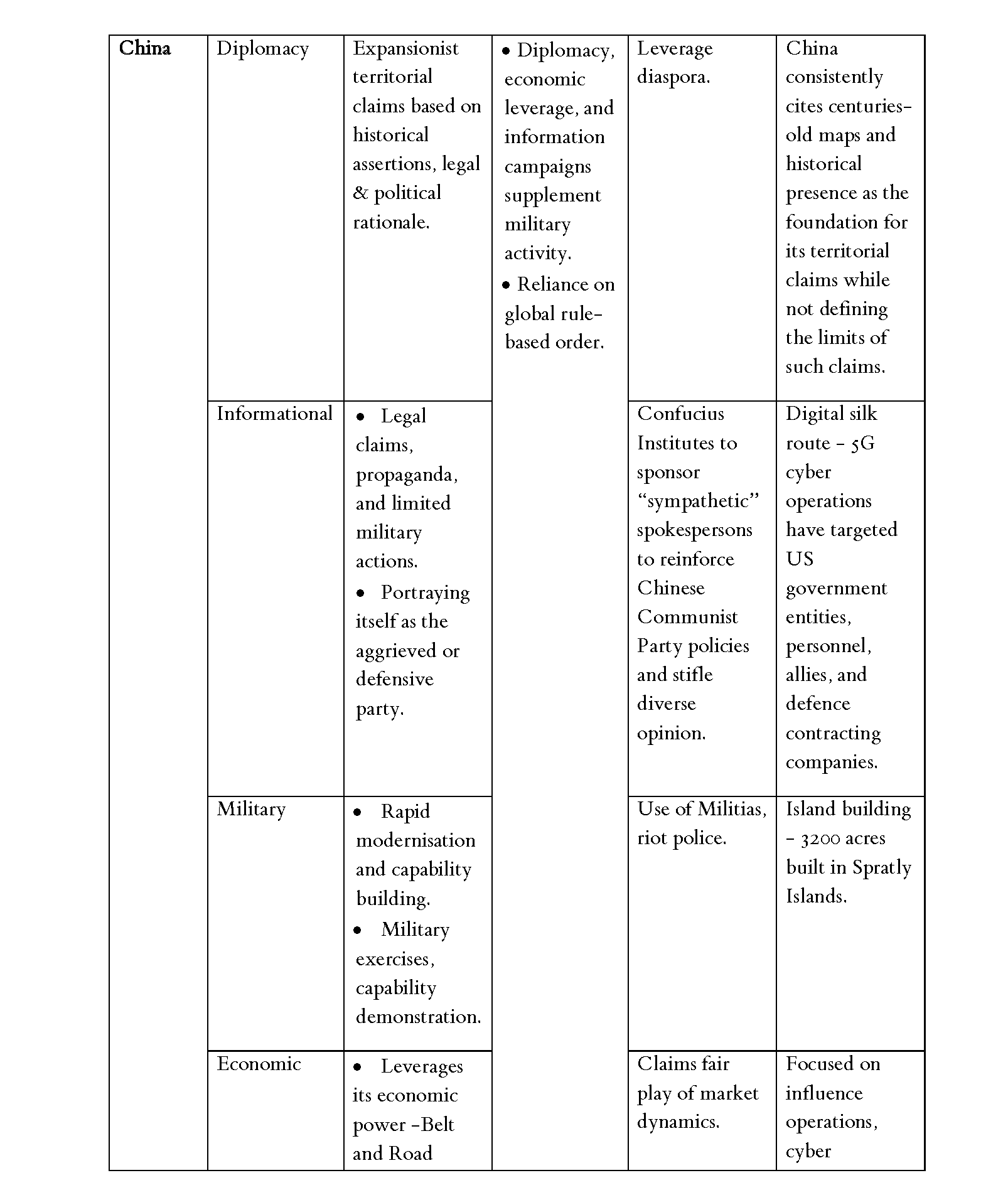

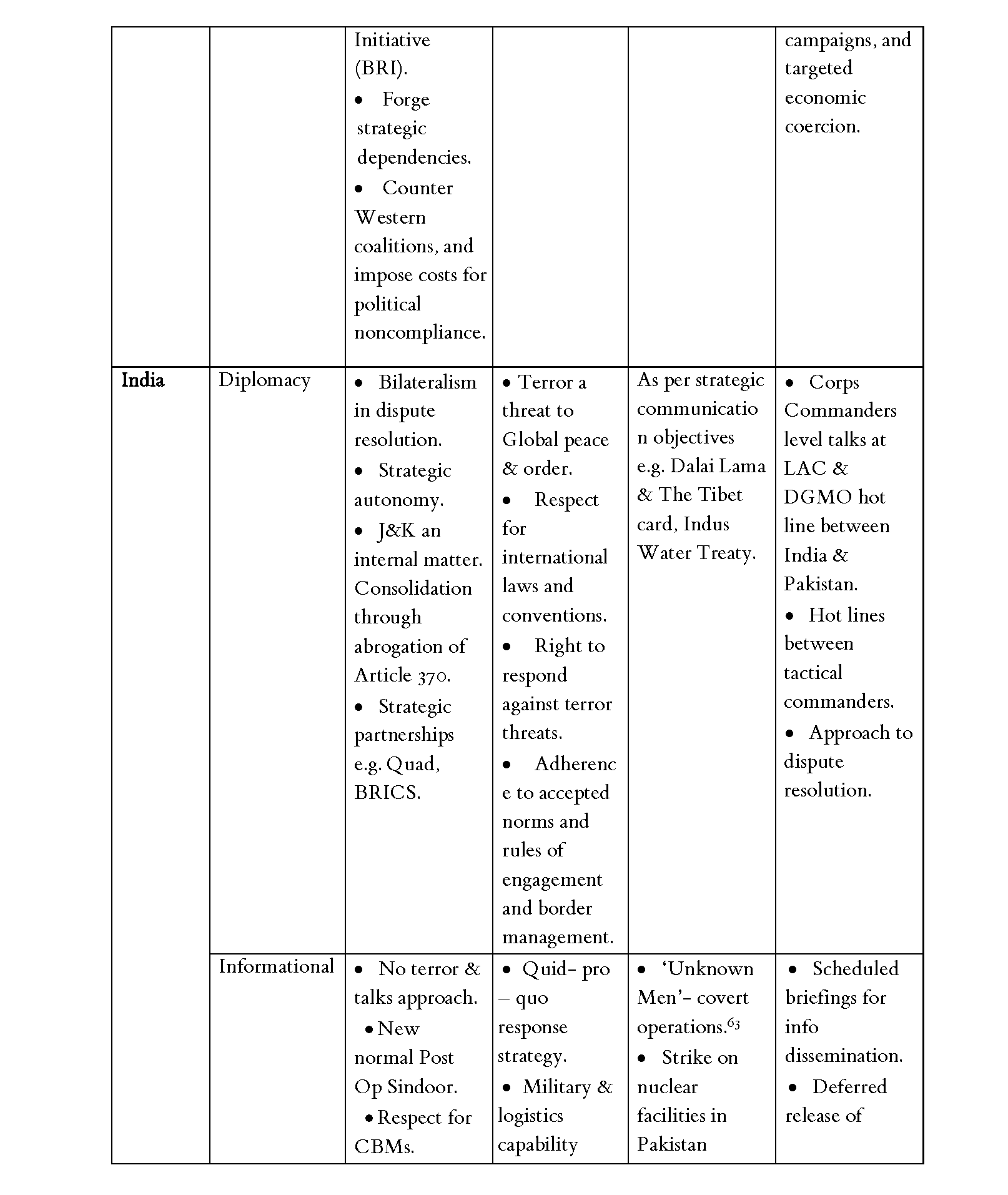

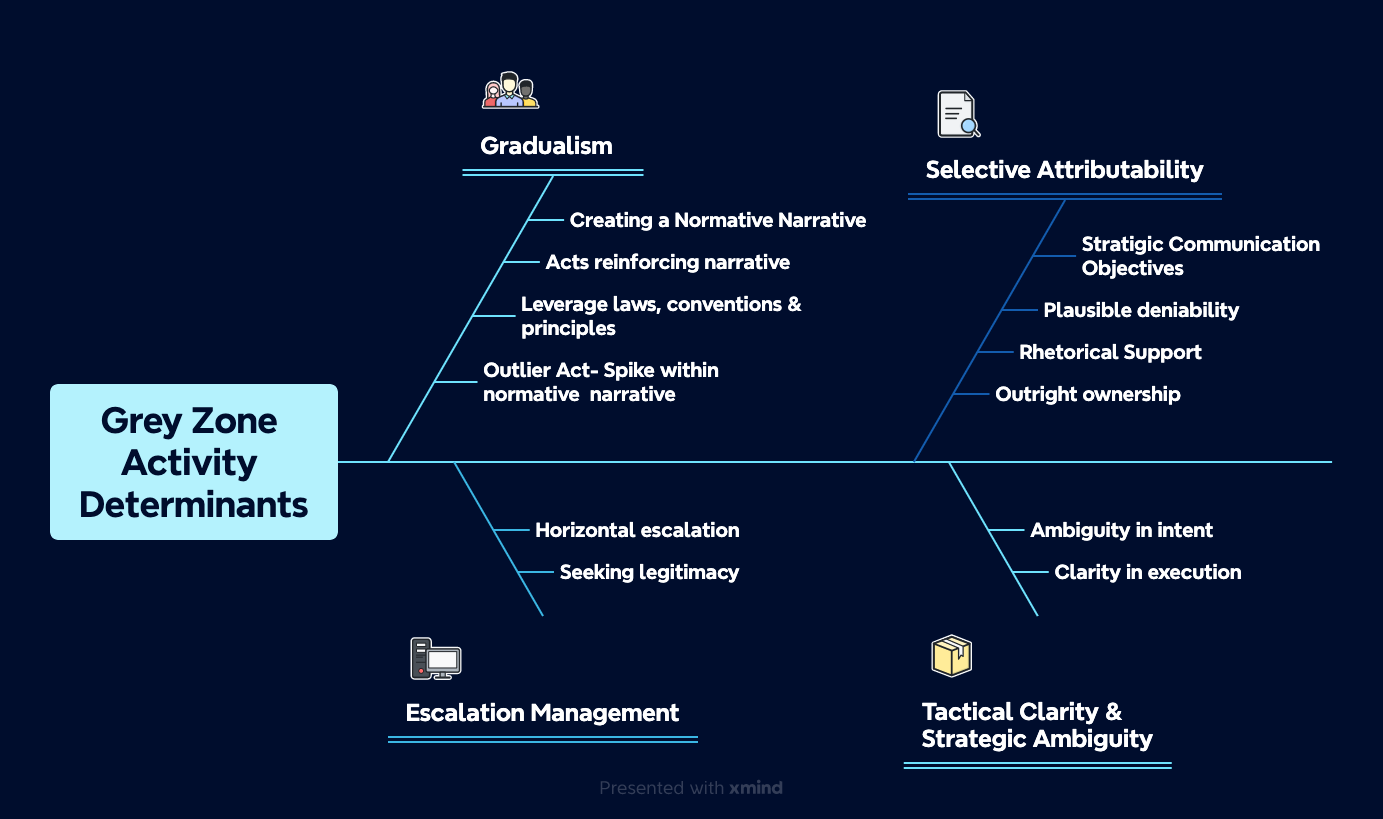

The paper highlights the significance of determinants such as gradualism, escalation management, selective attributability, and maintaining tactical clarity alongside strategic ambiguity in shaping and sustaining Grey Zone campaigns. Based on the determinants, a ‘funnel test’ is introduced for policymakers to evaluate whether a given activity truly fits as a Grey Zone action.

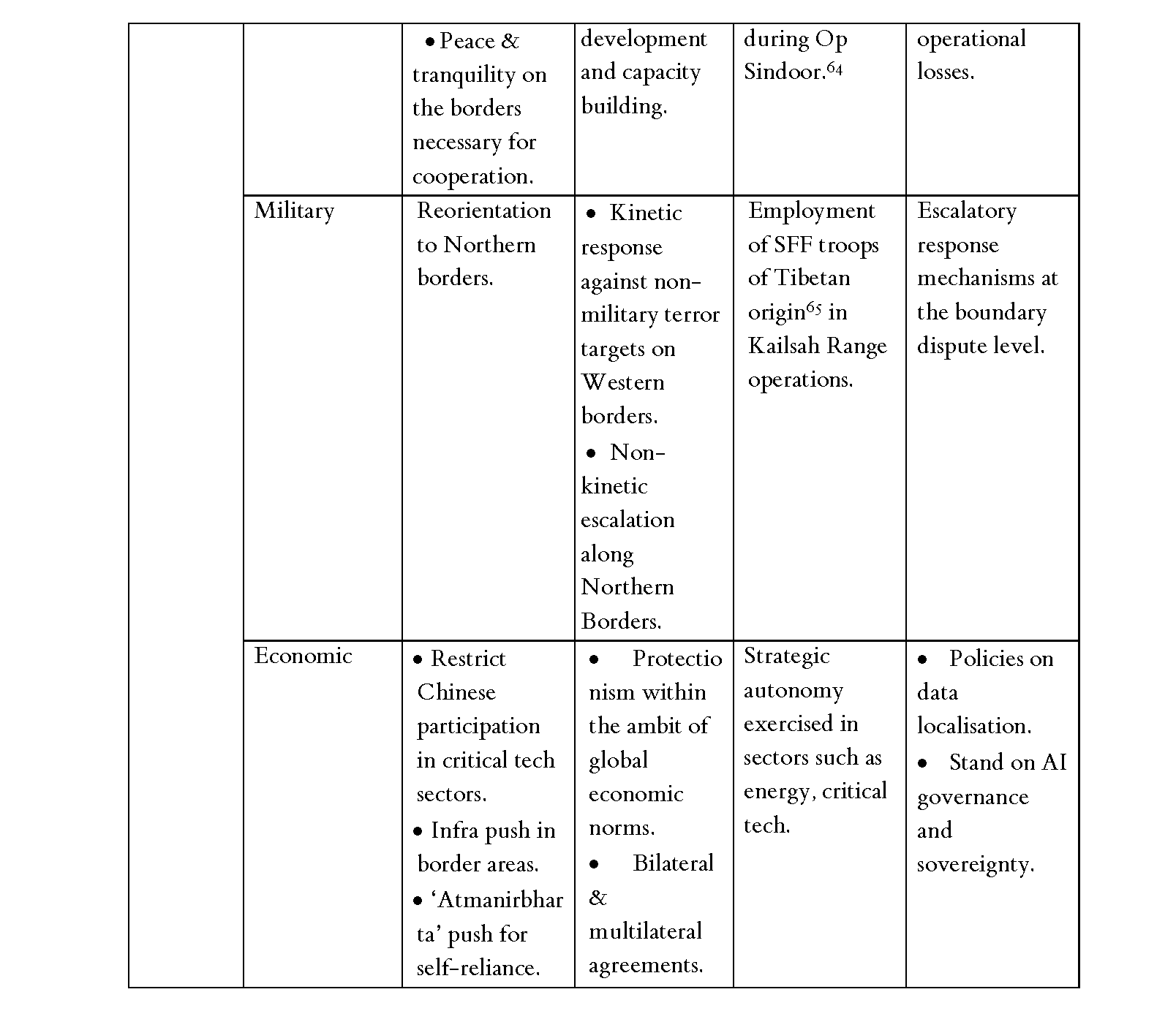

A multi-domain matrix (diplomatic, informational, military, economic; including Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) and cyber) links observable behaviours to likely intent, escalation pathways, and suitable cross-domain responses for Indian decision-makers.

Acknowledgments The author would like to thank Aditya Ramanathan, Manoj Kewalramani, Ameya Naik and Lokendra Sharma for their valuable feedback and comments.

- The framework is proof-tested against salient episodes involving India, Pakistan, and China to evaluate the conceptual relevance of Grey Zone contestations. From Pulwama-Balakot, the Galwan clash, and Operation Sindoor to intermittent coercive signalling and countermeasures. The framework demonstrates the persistence of Grey Zone campaigns, their episodic spikes, and the role of information operations in escalation management. This analysis will facilitate a deeper understanding of India’s security calculus and offer policy-relevant tools for prognosing and countering evolving Grey Zone threats.

AI tools have been used for feedback and review.

1 Introduction

The term ‘Grey Zone’ has gathered traction in the lexicon of conflict or war strategies in the post-Cold War era, especially since the US-led ‘global war on terror’. Other terms, such as Hybrid warfare, Asymmetric warfare, Unrestricted warfare, Fourth Generation Warfare (4GW), and Irregular warfare1 , which tend to describe the character of various conflicts, have also found their way into the discourse on the utility of force for coercion between states, as also between states & non-state actors. This paper examines Grey Zone threats and their relevance to India’s security challenges.

Is the Grey Zone a form of warfare or an operating space for the conduct of various forms of warfare?

Is the Grey Zone a form of warfare, or an operating space between the extremities of the conflict spectrum? How do we approach the range of coercive contestations bounded by ‘Peace (White)’ at one end and ‘War (Black)’ at the other extremity? Is it the intervening space within which actors (state/ non-state) resort to coercion using varied forms of warfare?

Distinguishing between ‘War’ and ‘Warfare’, Collin Gray explains that “war is a relationship between belligerents, not necessarily states. Warfare is the conduct of war, primarily, though not exclusively, by military means. The two concepts are not synonymous. There is more to war than warfare.”2

To put it simply, two actors may be at war, yet they do so by engaging in various forms of warfare through the continuum of conflict. War has a purpose, the ‘Why’, while warfare is about the means, the ‘What’—tools, instruments, weapons, and technologies—and the ‘How’—tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).

2 Defining Grey Zone

Various authors have proposed definitions of the Grey Zone, suggesting that it is a form of warfare or an application of tools of warfare below the threshold of war.

“The Grey Zone describes a set of activities that occur between peace (or cooperation) and war (or armed conflict). A multitude of activities fall into this murky in-between— from nefarious economic activities, influence operations, and cyberattacks to mercenary operations, assassinations, and disinformation campaigns. Generally, grey-zone activities are considered gradualist campaigns by state and non-state actors that combine non-military and quasi-military tools and fall below the threshold of armed conflict.”3 (Starling) [Emphasis added]

The above definition suggests an inclination to exclude military tools from the Grey Zone, which will exclude potent options from Grey Zone activities. It is, therefore, insufficient and may render the range of possibilities in the Grey Zone significantly limited. Regular and paramilitary forces have been employed extensively in Grey Zone campaigns. One instance is Border Action Team (BAT) raids by the Special Services Group (SSG) of Pakistan Army against Indian Army posts on the Line of Control (LoC).4 Another instance is the actions of Chinese Coast Guards (CCG) in disputed waters, intertwined with legal and cognitive warfare to amplify Beijing’s political narratives and strategic agendas.5

Vice Admiral R Harikumar has explained Grey Zone as a metaphorical state between war and peace, where an aggressor aims to reap either political or territorial gains associated with overt military aggression without crossing the threshold of open warfare against a powerful adversary.6 A reference to the asymmetry between belligerents here indicates that in a contestation, a lesser power indulges in actions in the Grey Zone, which is not entirely accurate. For example, the US has effectively leveraged the Grey Zone in several contests against peer or inferior powers, for instance, arming the ‘Mujahideen’ against Soviet Russia during the Cold War, propagating the narrative of violation of international laws and possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) to justify the Gulf Wars and overthrow of Saddam regime, and collaborating with the Northern Alliance in its operations to combat the Taliban during Operation Enduring Freedom.

A proposed definition states that Grey Zone conflicts comprise activities beyond the zone of peace but below the threshold of overt war or aggression. These are dubious, mostly illegal,covert, clandestine acts conducted over a prolonged period of time in a diffused manner using all possible means at the disposal of a state or anon-state actor. These aim to achieve political or any other socioeconomic or military objectives with deniability to avoid direct military response from the target state or group.7

According to a 2019 report of CSIS, Grey Zone activities are a series of efforts towards achieving one’s security objectives at the expense of a rival using means beyond routine statecraft and below direct military conflict. In engaging in a gr(e)y zone approach, an actor seeks to avoid crossing a threshold that results in open war.8

2.1 A Proposed Definition

The above definitions include the semantic features of the ‘Grey Zone’, i.e. gradualism, escalation management to remain below the threshold of war, and linkages to long-term strategic objectives. While partly accepting the above definitions, the proposed definition questions the emphasis on non-attributability and the resultant limitation on using conventional military as a tool. Non-attributability is a deliberate choice in strategic communication – a choice that may be predominant, yet not sacrosanct. For example, the transborder use of Special Forces by the Indian Army in Myanmar on 09 June 2015,9 as an action, delivered a statement of intent much beyond its tactical impact. The act ensured escalation control by its limited operational impact, probably with a tacit understanding with the country’s government, while making a wider regional strategic statement. Special forces have also been used earlier for similar operations, with shallow tactical depth, where non-attributability has been maintained. A proposed definition is thus as follows,

The ‘Grey Zone’ constitutes an overarching operational space of coercive struggles between actors (state and non-state) across multiple domains below the threshold of war, aimed at shaping the environment to achieve geopolitical objectives.

The proposed definition simplifies understanding the Grey Zone as an operational space.10 A space within which the ‘hows’ and ‘whats’ of warfare are orchestrated below the threshold of war to construct a normative narrative gradually. Therefore, a few terms that merit further explanation are the spectrum of conflict and escalation control, actors in conflict and the factor of attributability, domains of conflict and the tools of application.

2.2 Spectrum of Conflict: Between War & Peace

The Indian Army’s Land Warfare Doctrine 2018 foretells future security challenges, including conflicts characterised by operations in a zone of ambiguity where nations are neither at peace nor at war—a Grey Zone.11

The UK Defence Doctrine of 2022 relies on the definition of war as a state of armed conflict between different countries or different groups within a country.12 This definition is about the relationship between actors engaged in war. It also reiterates that the ‘nature of war’ remains enduringly unchanged. War remains violent, competitive and chaotic in its manifestation. At the same time, warfare has a changing character, mutating and adapting to the emerging geopolitical context and technological, societal, economic and cultural evolution.13

The purpose of war is best defined by Clauszewitz’s definition, “[w]ar is a mere continuation of policy by other means”.14 Threats in the Grey Zone afford a wide range of other means below the threshold of war. These include conventional and sub-conventional forms of warfare, using non-kinetic or kinetic tools, in a contact or non-contact manner. Therefore, unlike war, which has a beginning and an end, actions in the Grey Zone conform to a contest in perpetuity. It is a zone or operating space within which warfare, in its evolving character, manifests as a continuum below the threshold of war.

Peace is the more elusive of the two. Based on an experiential understanding of the state of being at peace, it is often interpreted in relative terms. For example, India and Pakistan have been at war on four occasions, i.e. 1947-48 (limited in geography), 1965, 1971 and 1999 (limited in geography) and in a state of ‘No war, No Peace’ intermittently. Also, as categorised in the journal article titled Armed Conflicts – 1946- 2001: A New Dataset,15 based on the intensity of violence, the ongoing conflicts involving India, through the years, have been categorised as ‘minor, intermediate and war’.16

Absolute peace is a misnomer. In his introduction to the translation of ‘On War - Volume 1’, Col F N Maude states, “an equilibrium of forces maintains peace.”17 Equilibrium of forces (not meaning military force alone), as a derivative of comprehensive national power (CNP) in the context of interstate competition, is dynamic and not absolute. Therefore, it can be argued that states will relentlessly contest the competitive space, seeking an equilibrium.

Grey Zone threats reinforce a sense of sustained relative peace, while exploiting disruptions (in cognitive space) or violence (in physical space) for coercion, to emerge in a position of strategic advantage as and when an equilibrium is reached.

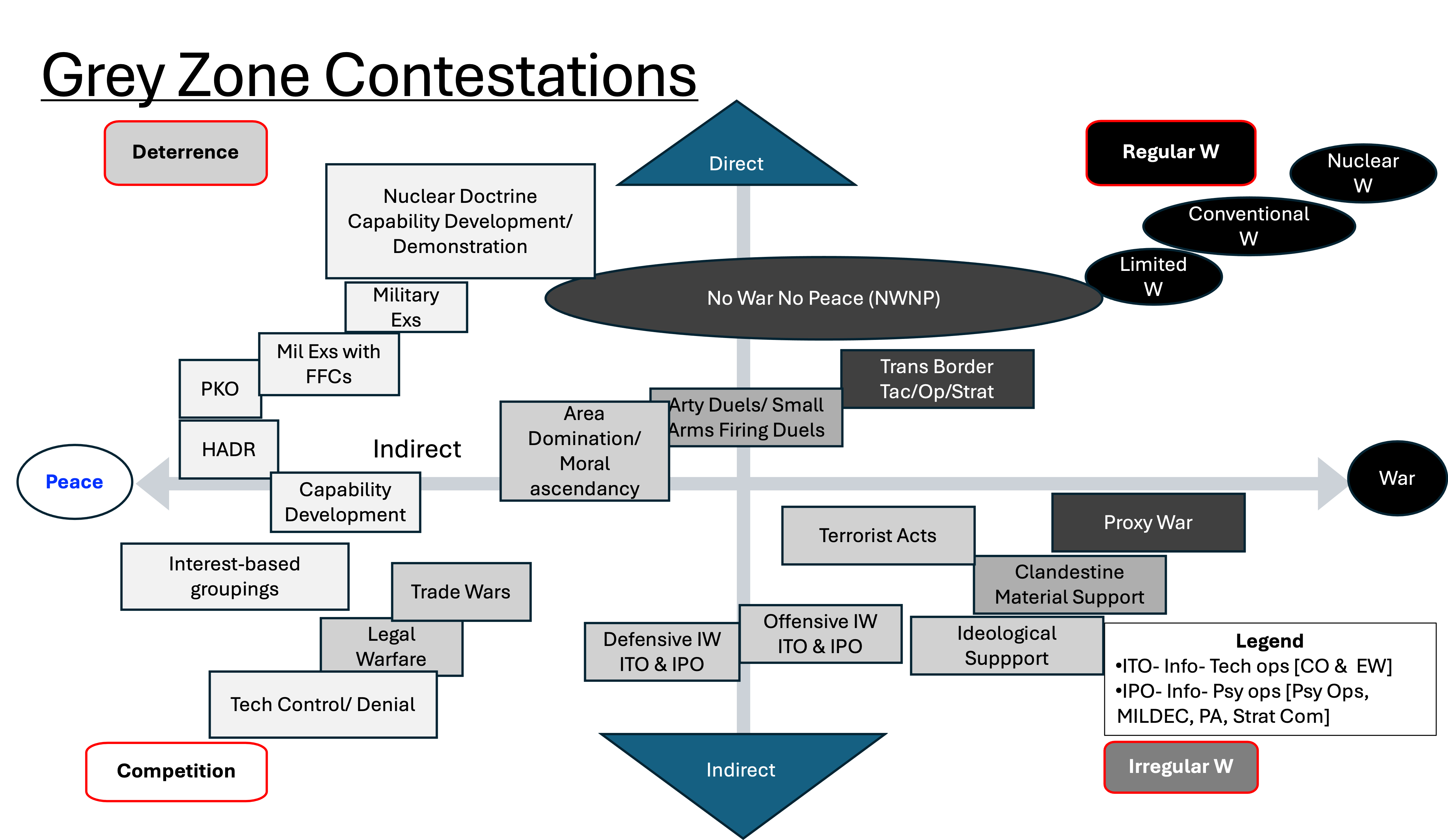

2.3 Spectrum of Conflict & Escalation Control – Grey Zone Encompasses Everything in Between

Robert S Burrell explains a full-spectrum conflict design in a two-dimensional visualisation, building upon an essay by Eric Robinson .18 The conflict spectrum (Figure 1) has ‘Peace’ and ‘War’ as the two extremities of the continuum of conflict along the X-axis. The dimension of ‘Means’ (not limited to military) from the ‘Ends, Ways, and Means’ approach to strategy formulation is extended along the Y-axis, with ‘Direct’ and ‘Indirect’ actions being the two extremities of means of conduct of warfare.19

The full-spectrum conflict design in a two-dimensional visualisation, has ‘Peace’ and ‘War’ as the two extremities of the continuum of conflict along the X-axis. ‘Means’ extended along the Y-axis, with ‘Direct’ and ‘Indirect’ actions being the two extremities. The resulting quadrants are Regular Warfare, Irregular Warfare, Competition and Deterrence.

Abbreviations used HADR-Humanitarian Aid & Disaster Relief, FFC- Friendly Foreign Countries, PKO-Peace Keeping Operations, IW- Information Warfare, ITO- Information- Technical Operations, CO- Cyberspace operations, EW- Electronic Warfare, IPO- Information- Psychological Operations, PA- Public Affairs, Psy Ops- Psychological Operations, MILDEC- Military Deception, Strat Com- Strategic Communications.

The Grey Zone operational space is divided into four quadrants,as given below.

- First quadrant: Regular warfare.

- Second quadrant: Irregular warfare.

- Third quadrant: Competition.

- Fourth quadrant: Deterrence.

Some activities have been illustrated in each quadrant, although not based on any data set. Due to their inherent interdependencies, the framework’s connotation of means can be expanded beyond military resources / instruments used in conflict to others, such as diplomatic, informational, and economic means (DIME).

The ‘Informational’ instrument will remain central to the model as resultant effects will manifest in the information domain. The Grey Zone, as a nebulous multi-dimensional operational space, transcends all the quadrants.

2.3.1 Regular Warfare

The first quadrant (highest intensity of violence) is ‘Regular Warfare’ using direct overt military means in increasing intensity, extending along the escalatory continuum to war, including nuclear war at the highest end of the spectrum. Some events in the Indian context in this quadrant were the 1962 Sino-India conflict, the 1965 and 1971 Indo–Pakistan wars, the Limited war of Kargil in 1999, transborder tactical raids, including ‘surgical strikes’ of 29 September 2016 in the Line of Control sector, the Balakot strikes on 26 February 2019 and Op Sindoor in May 2025. Military, diplomacy, and economic actions will play out in this quadrant, with the military instrument setting the stage for diplomacy, while economics (economic viability/ war-waging stamina) will determine the ability to sustain the war effort over time.

2.3.2 Irregular Warfare

The second quadrant is that of ‘Irregular Warfare’ (low-intensity violence with high visibility) without the overt use of military force, with plausible deniability or non-attributability, which is in the form of proxies through ideological and/ or material support, for example, the J&K militancy, the insurgencies in the North East, Cyber Warfare, narco-terrorism20, Fake Indian Currency Note (FICN) circulation etc.

The perceived intensity of violence in this quadrant will remain below the threshold of war, without violating normative ‘red lines’ to ensure escalation control. The targets in this quadrant are population-centric, with greater reliance on ‘effects’ in the cognitive domain through violence in the physical domain, to achieve objectives in the information/psychological/perception domain than the physical domain. Informational, diplomatic and military instruments will sustain the effort in this quadrant at an acceptable economic cost.

The objective in this quadrant is to create a normative narrative over a prolonged period. Pakistan, for example, over the years, has created a narrative of homegrown insurgency in J&K, with regular incidences of low-intensity violence in the state of J&K. A similar narrative of terrorism due to internal societal faultlines has also been created by supporting terror organisations like Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) or Indian Mujahideen (IM), fostering a latent acceptance of random terror incidents in the country.

India accepted it politically as an enduring security risk without triggering a disproportionate response. Similarly, China has been staking territorial claims in Ladakh, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh, reinforcing the narrative through cartographic aggression and constructing dual-use infrastructure such as border villages.21

2.3.3 Competition

The third quadrant is that of ‘Competition’ (least intensity of violence), which will be primarily driven in the economic and diplomatic domains to secure common interests while attempting to carve out mutually agreeable mechanisms (treaties, Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), and Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs)) to build confidence and promote prolonged peace.

However, in the third quadrant, as the locus of competition shifts towards the intersection of the two axes, the stress of competing or conflicting interests will strain relations, thereby escalating actions in the second or first quadrant. Points of leverage such as political vulnerabilities, societal fault lines, or systemic vulnerabilities (provisions of law, cyber vulnerabilities, etc.), are identified, profiled, and invested in by a perpetrator in the Grey Zone (while still in this quadrant) through efforts such as intelligence operations, cyber operations, etc.

These identified vulnerabilities may be exploited through future actions, such as supporting insurgencies through proxies, information warfare campaigns, kinetic actions such as border clashes, and non-kinetic offensive cyber-attacks, which fall in the second quadrant.

In this quadrant, the focus of the military instrument will be on capability building to retain a favourable force asymmetry to deter a confrontation. For example, the Peace & Tranquillity Agreement (1993) between India & China to manage the boundary conflict was effective. However, India’s focused infrastructure development and capacity building challenged the prevailing equilibrium, triggering a series of Chinese actions escalating border tensions between 2013 and 202022, indicating an aggressive counter-strategy by China, finally leading to the Galwan clash in Jun 2020.

2.3.4 Deterrence

The fourth quadrant is deterrence, as defined below.

“[T]he practice of discouraging or restraining someone— in world politics, usually a nation-state—from taking unwanted actions, such as an armed attack. It involves an effort to stop or prevent an action, as opposed to the closely related but distinct concept of “compellence,” which is an effort to force an actor to do something.”23

M J Mazarr affirms,

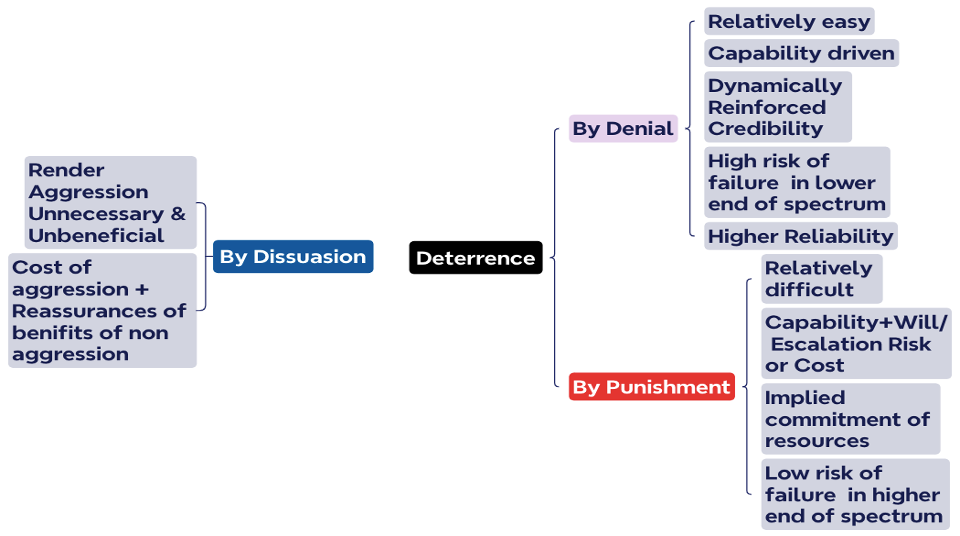

” [I]t is the perceptions of the potential aggressor that matter, not the actual prospects for victory or the objectively measured consequences of an attack. Perceptions are the dominant variable in deterrence success or failure.”24 [Emphasis added] Figure 2 shows a mind map that can be used to understand the complexities involved in achieving deterrence. As explained below, an aggressor can be deterred by two forms of deterrence: denial or punishment.

2.3.4.1 Deterrence by Denial

This strategy is driven by the defender’s perceived capability to deny the aggressor its intended objectives. This perception has to be regularly reinforced through the information domain. This form of deterrence is relatively easy to achieve and more reliable at the higher end of the conflict spectrum. It has a higher risk of failure at the lower end of the spectrum, as the defender would not find it cost-effective to unleash its deterrent capabilities against minor or below-the-threshold infringements.

2.3.4.2 Deterrence by Punishment

A combination of two factors drives this strategy. First, the defender’s perceived capability and second, the defender’s will to inflict prohibitive costs on the aggressor.It is weighed against the escalation risk or cost the defender will bear to deter a potential aggressor. This form of deterrence is relatively complex to achieve and more cost-intensive. It makes it imperative to maintain capabilities in a perpetually higher state of readiness to reinforce the perception of imminent threat of punishment. This has a lower risk of failure at the higher end of the spectrum, as the perpetual state of readiness of the defender is more likely to deter a potential aggressor from attempting infringements. The lower end of the spectrum remains vulnerable to challenging deterrence due to perceived low costs for infringements.

2.3.4.3 Dissuasion

This strategy entails a two-pronged approach: threatening to impose costs for aggression and promising benefits or reassurances for non-aggression. The goal of dissuasion is to convince a potential attacker that the cost-benefit calculus of aggression is unfavourable.25 This strategy is more likely to succeed in peer contestations by providing political space for manoeuvring domestic public opinion.

2.3.4.4 Cross-Domain Deterrence (CDD)

The nebulous nature of the Grey Zone operational space adds further complexity to the concept of deterrence. Consequently, CDD is a more suitable construct that adaptively lends itself to application in the Grey Zone. CDD is defined as

“[T]he use of threats of one type, or some combination of different types, to dissuade a target from taking actions of another type to attempt to change the status quo. More simply, CDD is the use of unlike technological means for the political ends of deterrence.”26

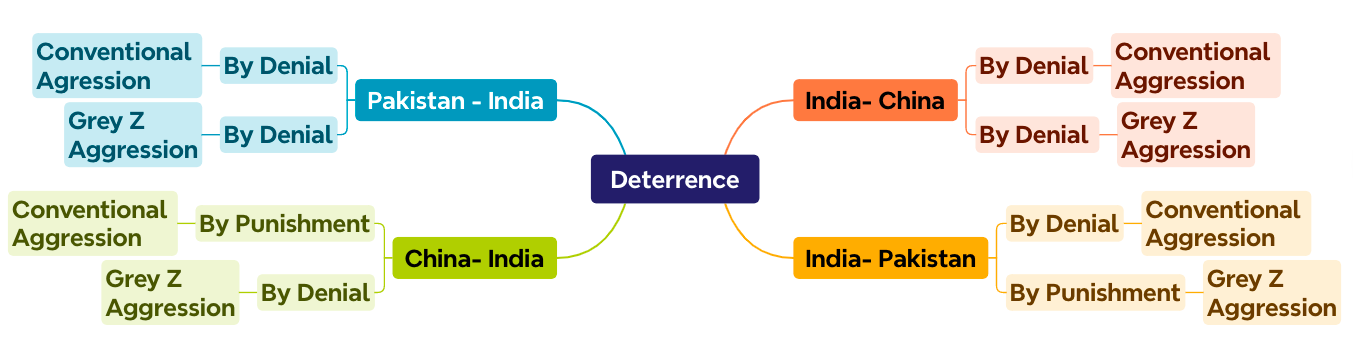

Figure 3 explains the deterrence possibilities in the Indian neighbourhood between India, Pakistan and China in light of the construct of deterrence discussed above.

In the Sino-India context, there is conventional and Grey Zone asymmetry in favour of China. India deters China by denial, whereas China deters India by threat of punishment in the conventional space and by denial in the Grey Zone.

In the Indo-Pak context, India enjoys a marginal conventional advantage while Pakistan enjoys a definite advantage in the Grey Zone. India deters Pakistan by denial in the conventional space. It has gradually migrated to deterrence by punishment in the Grey Zone , whereas Pakistan attempts to deter India by denial in both the conventional and Grey Zone space.

It is acknowledged that the above deterrence possibilities simplify the understanding of cross-domain deterrence dynamics in this complex geopolitical equation.

The actions in this quadrant will reinforce deterrence through informational & military means.

- The actions may include, in the informational realm, publicly stated doctrines, defined redlines, and military activities aimed at strategic signalling.

- These actions may consist of military exercises, manoeuvres, and testing of conventional/ strategic vectors to demonstrate commitment to stated doctrines, such as the development of a ‘Triad’ to reinforce India’s doctrine of credible minimum deterrence and assured second strike27 or Pakistan’s development of Tactical Nuclear Weapons.

- Military exercises with friendly foreign countries (FFCs) signal the state of operational integration and preparedness of international cooperative groupings.

- Threats of a worst-case escalation and limited tactical use of force to retain moral ascendancy in areas of ambiguity, such as trans-Line of Control raids, artillery duels and firing.

In this quadrant, when actions by a dominant actor lead to effective deterrence in favour of the dominant actor, the target state is more likely to be pushed to exploit the second or third quadrant, as the only available option to counter coercion and unshackle itself from a deterrence bind. The dynamics of diplomacy and military instruments will be predominant in this quadrant.

The scope for exploiting ‘Grey Zone’ operational space exists in all four quadrants, with nebulous physical and cognitive boundaries. Non-attributability or plausible deniability will be inherent to the perpetrator’s design for retaining escalation control, but not a binding compulsion in alignment with the strategic signalling objectives. Actions in each quadrant have intrinsic escalatory dynamics, with escalatory actions likely to transition to another quadrant.

2.3.5 Multiple Domains of Grey Zone Operational Space

Grey Zone threats involve the coordinated and cogent application of all instruments of power at the disposal of a state or a non-state actor across multiple domains. The colloquial term “domain” has both geographical and functional connotations.28

The principal objective in the Grey Zone is for the dominant power to achieve and retain a state of equilibrium of power from a position of strategic advantage, and for a contesting power to disturb the equilibrium within a viable risk calculus.

A multi-domain operational environment includes the physical domains, i.e. Land, Maritime and Aerospace, and the cognitive domain, i.e. the Electromagnetic Spectrum (EMS) and the Information-Cyber Space. The significant streams of Information Warfare are distinctly different: Information-Technical Operations (ITO), comprising Cyberspace Operations (CO) and Electronic Warfare (EW) functions; and Information-Psychological Operations (IPO), covering Psychological Operations (PSYOP), Military Deception (MILDEC), Public Affairs (PA), and Strategic Communication (SC).29

The principal objective in the Grey Zone is for the dominant power to achieve and retain a state of equilibrium of power to ensure lasting relative peace (through deterrence or cooperation) from a position of strategic advantage, and for a contesting power to disturb the equilibrium within a viable risk calculus. Actions in the Grey Zone are cost-effective options for a geopolitical paradigm of constant contestation.

Failure of deterrence or escalation control due to miscalculating a Grey Zone action can result in an indecisive, prolonged military confrontation or a cost-prohibitive war. For example, in the India-Pakistan context, while conventional deterrence has most of the time prevented full-scale war, a ‘No War, No Peace’ situation has prevailed in the Line of Control (LC) sector. This could have been upended if the Balakot or Op Sindoor escalatory dynamics had spiralled out of control. An ambiguous narrative of the right to respond against state-sponsored terrorism was relied upon by India for legitimacy as well as escalation control, in the absence of any globally accepted definition of terrorism.

As per the 2019 CSIS International Security Programme report, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea have been the principal Grey Zone actors undermining US interests. The seven components of the Grey Zone toolkit employed by these actors have been information operations and disinformation, political coercion, economic coercion, cyber operations, space operations, support to proxies, and provocation by state-controlled forces.30 These can have multi-quadrant manifestations, as explained in section 2.3. above.

2.3.6 Strategy at play in the Grey Zone

Diplomatic, informational, military and economic (DIME) instruments of power are in a constant and dynamic interplay. The primacy of instruments may be modulated while maintaining complementarity to optimise the cumulative effect of the power projected. The informational domain is omnipresent, a strategic substrate. Individual events in the Grey Zone will, over time, add up to a larger whole than the sum of their effects. The complexity of strategy dynamics in Grey Zone operational space is as relevant as Everett Dolman argues in terms of understanding strategy at large, in stating,

“[A]t the tactical level, the issue of deciding a victor is relatively straightforward. Tangible objectives such as relative casualties, physical control of territory, and public sentiment can be measured, and under these pre-established criteria, a victor assigned. At the strategic level, one quickly loses faith in such calculations. It is quite possible to win the battle and lose the war. It is moreover possible to win the war and lose the strategic advantage.”31

2.3.7 Timelessness of the Dimension of Time

The dimension of ‘Time’ is significant in the context of actions in the Grey Zone. Grey Zone actions don’t have classical victories and defeats. The ebbs and flows of these contestations play out over extended periods, setting the stage or shaping the space for applying other instruments of power, whether to attain a particular objective or to achieve strategic advantage in the quest for equilibrium.

Gradualism and incremental gains through effects help forge a norm, with escalation management inherent in the narrative. General Sabharwal argues that Grey Zone strategies generally combine several tools such as political, diplomatic, informational, covert or cyber in a way that is intended to achieve strategic ends over time without triggering a conventional and high-risk armed conflict.32

Persistent actions in the Grey Zone to support a narrative facilitate the creation of an acceptable normative pattern in favour of the perpetrator – a dominant popular narrative. Actions conforming to this normative narrative prevent escalation until an outlier act, by design or miscalculation, crosses a red line. This may lead to escalation and doctrinal shifts over a period.

For example, in the context of Pakistan’s proxy war against India, the 13 December 2001 Parliament attack, coming close on the heels of the 9/11 attacks on the US, crossed a red line in the acceptable norm of proxy war limited to Jammu and Kashmir. It was an act of terrorism, symbolically targeting the very seat of India’s democracy. This led to an escalation in the form of Op Parakram, and the subsequent evolution of the Proactive Operations Strategy (PAS), also referred to as the ‘Cold Start Doctrine’ in the succeeding decade by India.

This was followed by the Azm-e-Nou series of exercises (2009-2013) by Pakistan, to evolve and validate a strategy of offensive defence enunciated by the New Concept of War Fighting (NCWF)33 and resultant Rearticulation-Reorganisation-Relocation (RRR)34. On the strategic deterrence front, it led to a doctrinal shift by Pakistan from a ‘Minimum Deterrence’ posture towards a ‘Full Spectrum Deterrence’35 , which included the development of a ‘Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNW)’ programme along with a “liberty to select from a range of counter-value, battlefield, and counterforce targets.”36

Throughout the ensuing decade, however, all of these did not deter Pakistan from planning, supporting, and executing – through its proxies – the July 2006 serial train blast in Mumbai, the May 2008 serial blasts in Jaipur, the July 2008 Kabul Embassy attack, or the ‘26/11’ Mumbai attack. This, over time, led to strategic rethinking in India towards a ‘Dynamic Response strategy (DRS)’37.

A redrawing of ‘red lines’ occurs through an information campaign and escalatory military actions. During the currency of an ongoing contestation, redlines are tested or challenged, and a shift in the normative narrative is triggered. Therefore, an expansion of the Grey Zone operational space takes place. For instance, in the aftermath of the Uri attack (18 September 2016), multiple raids (28 September 2016) were conducted against trans-LoC terror infrastructure, across a wide front. What was until then a Grey Zone response paradigm – transborder raids using Special Forces or Ghatak Platoons38 by the Indian Army, or Border Action Team (BAT) actions by the Pakistan Army, without attributability – was openly claimed as a strategic communication objective by the Government of India. The shift was in the informational domain: to attribute the raids to its Special Forces; while restricting the narrative to targeting of terror infrastructure, and not the Pakistan Army; in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (LoC Sector), which (as disputed territory) is geographically a Grey Zone.

Similarly, in the aftermath of the Pulwama attack (14 February 2019), India responded with an unprecedented escalatory response through airstrikes on Balakot (26 February 2019), located in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, in Pakistan’s mainland, beyond the LoC sector, which it later declared as pre-emptive strikes targeting a Jaish e Mohammed (JeM) training camp. JeM, as a proxy of Pakistan, is again a Grey Zone actor.

This was to ensure escalation control, by projecting an informational narrative of targeting terror infrastructure in Pakistan, which had become a global norm due to a paradigm established during the ‘Global War on Terror’.

Pakistan had no option but to respond as per its ‘notch above response’ or a ‘Quid Pro Quo Plus’39 response strategy. Pakistan, after its retaliation, named ‘Swift Retort’, on February 27, through its Foreign Office, stated that the strikes were carried out at “non-military targets, avoiding human loss and collateral damage.”40 This again indicates Pakistan’s reliance on the Grey Zone in the informational domain to manage escalation.

The entire escalatory episode therefore highlights the Grey Zone operational space and its expanse, wherein acts of terror have escalated to conventional force contestations in the air, managed through a counterterror and restrained response narrative.

The shifting narratives concerning attributability, tools of action and response, justifications for legitimising responses, and a doctrinal shift toward creating space for conventional tools while managing escalation, all outline the nebulous limits of the Grey Zone operational space.

3 Funnel Test for Grey Zone Activities

Based on the proposed definition, a four-quadrant Grey Zone contestation matrix in sections II above, four determinant qualities emerge, which can be used to profile Grey Zone threats. An activity within each of the four quadrants can have attributes of Grey Zone, while appearing as a Regular War / Irregular War / Competition / Deterrence activity. These are shown in Figure 4, explained below, and proof tested in the context of Pakistan, China, and India in the Appendix.

3.1 Gradualism

The Grey Zone relies on long gestation periods, running into decades, over which normative narratives are created and gradually reinforced through a series of conforming actions.41 These depend on prevailing laws, conventions and principles to persist below the threshold of conflict. Once in a while, an outlier act whether by miscalculation or design can create a spike in intensity, leading to escalation and consequently the thresholds or ‘red lines’ get revised.

3.2 Escalation Management

The perpetrator has to adapt their instruments to exploit the Grey Zone to manage escalation. This is done by continuously seeking legitimacy for its actions within the framework of the normative narrative that gradualism creates. In the one-off case where an outlier act triggers escalation, the effort is focused on managing the fallout within that domain.

For example, in the India-China context after the Galwan clash (2020), both sides resorted to enhanced troop deployment along the LAC to cater to the mobilisation differential. In the India-Pakistan context, in phase 1 (07 May 2025) of Op Sindoor, India restricted its choice of targets to terror infrastructure signalling to Pakistan that its immediate objectives had been met. As Pakistan resorted to its ‘notch above’ response, India further escalated its targeting to military infrastructure in phase 2 (09/10 May 2025) instead of population or economic targets. On the other hand, Pakistan, to assuage domestic public opinion, claimed victory based on aircraft losses inflicted upon the Indian Air Force (IAF). This, despite the IAF, with impunity, inflicting considerable attrition to Pakistan’s critical military infrastructure. This shows the strategy to escalate while providing the adversary politically pliable ‘off ramps’ to de-escalate.

3.3 Selective Attributability

The factor of attributability is selectively considered, based on the overall objectives of Strategic Communication. It may range from plausible deniability (Pakistan denying involvement in Pahalgam terror attacks), rhetorical support (India’s support for the Tibetan cause), to outright ownership (Trans LC raids by Indian Special Forces post Uri terror attack).

3.4 Tactical Clarity with Strategic Ambiguity

Threats in the Grey Zone are characterised by tactical clarity in execution. This means that the perpetrator has clarity in resource allocation, mission tasking and control of the event and modulation of the impact. For example, during the terror attack in Pahalgam, targeted killing of tourists based on religion was resorted to while selectively restricting the killing to males only. In the Galwan clash, non-lethal riot equipment was used by PLA for lethal attack, despite ready availability of PLA regular as well as border defence troops with firearms.

This clear tactical level execution is done while retaining strategic ambiguity about the intended objectives of the tactical action, which causes decision dilemma in the minds of the institutional and national leadership of the target state.

Four determinant qualities emerge, which can be used to profile Grey Zone threats- gradualism, escalation management, selective attributability and tactical clarity with strategic ambiguity.

4 Grey Zone Snapshot: Testing the definition over a limited time window – Balakot, Galwan, Operation Sindoor

This section investigates the activities that fit into the Grey Zone definition and qualify the funnel test over a short period of time, covering major activities between the Balakot strikes by India in response to the Pulwama terror attack in February 2019, the Galwan clash in June 2020, and Operation Sindoor in May 2025. It is contextually embedded in the historical contestations in India’s neighbourhood, with India, Pakistan, and China as the principal actors.

This is done in correlation to the framework in Figure 1 above. The period has been selected to highlight the perpetuity and episodic manifestation of Grey Zone campaigns. The activities included in Figure 5 (below) are not all-inclusive; they only indicate the nature of the contestation, relying on the Grey Zone operational space to highlight the linkages with the proposed definition.

4.1 Pakistan Grey Zone Toolkit

During this period, Pakistan was undergoing tumultuous political, economic, and internal security challenges. A democratically-elected government, with Imran Khan as the PM, was ousted by a parliamentary no-confidence vote in 2022. He had fallen out of favour with the Army, which had engineered his victory in the earlier elections. The subsequent general elections in 2024 took place under the shadow of military influence, resulting in a hybrid government. The Pakistan Muslim League party (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) came to power with the active support – and under the control of – the Pakistan Army.42

Indian analysts believe that the Pakistan Army, the primary centre of power in the country, has three verticals, the Strategic Plans Division (SPD) for management of nuclear weapons; the DGMO for conventional warfare; Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) for running the proxy wars and Information Warfare (IW) through the DGISPR, plus its political arm for keeping the domestic situation favourable for the Army.43

4.1.1 Activities in the Irregular Warfare Quadrant

During this period, as part of its proxy war policy, in the second quadrant (irregular warfare), Pakistan continued to meddle in the Union Territory of J&K, India.

The so-called Bajwa doctrine was unveiled in early 2018, which predicted a rapprochement with India.44 In the face of growing US pressure to audit Pakistan’s commitment to US counterterror efforts before US withdrawal in August 2021, the counter-terror approach was likely to address India’s security concerns through state legitimacy to terrorists and radicals.45 In May 2018, a ceasefire was also reached on the LC, while the Indian Army ensured that moral ascendancy was retained through tactical initiative delegated to the local commanders, wherein Brigade Commanders were authorised to plan and execute tactical actions in response to ceasefire violations.46

The Bajwa doctrine was, however, shelved in favour of the Munir doctrine. Gen Asim Munir, in his speech to a gathering of over 1000 expatriates on 15 April, amplified the ‘Two Nation Theory’ and reiterated the indispensability of the Kashmir question by referring to it as Pakistan’s ‘Jugular Vein’ and pledged unending support to the separatists.

Pakistan continued using its proxies such as JeM or The Resistance Front (TRF), a mutated proxy of Lashkar e Taiba (LeT). Activities in the form of low-scale, low-visibility attacks against security forces and episodic high-scale, high-intensity attacks were perpetrated.

Pakistan’s intent through these episodic flashpoints was to exploit the second quadrant through adventurous opportunism, with the following objectives:

Firstly, dissipating domestic political pressure and reinforcing the stature of the Pakistan Army.

Secondly, internationalising Kashmir by reminding the world that this remains a potential flashpoint in a nuclear-armed region.

Thirdly, thwart India’s efforts to establish normalcy in J&K by targeting its consolidated political position and resurgent tourism economy, attempting to revive the ebbing insurgency.

4.1.2 Activities in the Competition Quadrant

On 18 August 2018, Pakistan, on the sidelines of the swearing-in of its 22nd PM, Mr Imran Khan, informally announced its decision to provide access to the revered Kartarpur Saheb, a place of Sikh pilgrimage in Pakistan, with a ’larger tactical game plan that the [Pakistan] army was developing to gain greater influence in Indian Punjab.47

India abrogated Article 370 on 05 August 2019 and continued its ‘no talks with terror policy’, leading to a period of no structured interactions between the two governments. Pakistan responded with a series of political, diplomatic, and economic measures characteristic of the third quadrant (competition). These included the expulsion of the Indian High Commissioner and the recall of its own, making emphatic appeals in the UN and to the international community, especially the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). It also discontinued the Thar Link express between Karachi and Jodhpur.

4.1.3 Activities in Deterrence Quadrant

Cooperation, collaboration, and collusion with China are key components of Pakistan’s security calculus. ‘Interoperability with the Chinese was a key Goal’48 as it also played out in Operation Sindoor in May 2025, where active sharing of Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) by the Chinese with Pakistan was evident.49

Pakistan has made repeated references to nuclear dynamics in the Indo-Pak relations to deny conventional operational space to India, where the latter enjoys an asymmetric advantage. In the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370, Imran Khan made an emphatic speech to the 76th Session of the UNGA, linking regional security to the J&K situation and stating that,

“[t]he onus remains on India to create a conducive environment for meaningful and result-oriented engagement with Pakistan.” Further emphasising, “[i]t is also essential to prevent another conflict between Pakistan and India. India’s military build-up, development of advanced nuclear weapons, and acquisition of destabilising conventional capabilities can erode mutual deterrence between the two countries.”50

In the aftermath of Operation Sindoor, as escalatory actions were being initiated by India and Pakistan, the Pakistan military declared that the PM had called a meeting of the Nuclear Command Authority51 to play up the nuclear card. China and Turkey have emerged as major suppliers of high-tech military hardware to Pakistan. 81% of Pakistan’s military hardware is of Chinese origin.52 This cooperation, collaboration, and collusion exacerbate India’s two-front dilemma by activities in the fourth quadrant.

4.1.4 Activities in Regular Warfare Quadrant

The activities in the first quadrant are discussed at the end of this snapshot, as the fundamental essence of campaigns in the Grey Zone is to avoid transition into this quadrant. However, a few examples will illustrate how activities in the other quadrants, primarily the IW domain, are used to manage escalation once miscalculations in the other quadrants cause the contestation to spill over into this quadrant.

Pakistan’s proxy war in J&K was aimed at gradually developing into a normative narrative of a homegrown local insurgency, expected to lead to a popular uprising. This misconception has been reinforced in Pakistani popular imagination over decades, with episodic spikes in the form of tribal intrusion: Operation Gulmarg (1947-48), Operation Grand Slam (1965), insurgency in J&K (since 1989), Operation Badr (1999), and a series of terror attacks already highlighted above.

As India adopted a paradigm of escalatory response to terror through kinetic, contact, and non-contact options in the post-Uri, Pulwama, and Pahalgam operations, Pakistan responded with a ‘notch above’ response in the same quadrant. This is a political compulsion for Pakistan. However, it relied on the IW domain – misinformation campaigns to manage escalation through a ‘notion of victory’ for domestic public consumption, and diplomacy to garner third-party intervention from the US for a ceasefire.

4.2 China’s Grey Zone Toolkit

President Xi Jinping emerged as the undisputed head of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the authoritarian regime of China, during this period. Removal of Presidential term limits in 2018 and an unprecedented third term in 2022 further consolidated his political position.53

In the past decade, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has implemented major reforms with an ambitious program to build a modern, informatized, and “world-class” force by 2035. The PLA Rocket Force reorganisation to an Information Support Force with emphasis on strategic domains – space, cyber, and electronic warfare – reinforces the PLA’s priorities. It has emerged as an industrial powerhouse, boasting a military-industrial complex leading in innovation and manufacturing.54

China’s economy maintained strong growth through most of this period, despite significant headwinds from the COVID-19 pandemic, global trade turbulence, and geopolitical competition. China posted real GDP growth rates of around 5% annually until 2025, with GDP projected to reach approximately $19.2 trillion.55

China has continued to leverage its Grey Zone toolkit during this period to pursue its strategic objectives, compete with the US, and undermine India. The Chinese concept of peacetime employment of military force explains China’s Grey Zone toolkit.56 This operational space has its escalatory dynamics ranging from and including the following.57

Baseline Military Deployments, such as the Fujian Rotational Deployments, which refers to the rotational deployment of PLAAF at Fujian since 1959; and Non-Standard Military Training, such as the 5.20 Deterrence Activity, which included a series of amphibious exercises in the Fujian region in May 2016, conform to the fourth quadrant.

Nationwide Readiness and Disposition Adjustment, also called the 922 Special Mission in 2020-21 (September 2020 to mid-2021), signalled to the US the Chinese state of readiness against any likely coercive use of force, which would be an activity at the cusp of the fourth and first quadrants.

Non-Lethal Military Confrontation, referred to as Hai Yang Shi You 981 Standoff or the Zhongjiannan Security Operation, involved ramming incidents between Chinese and Vietnamese forces in the disputed South China Sea and Lethal Military Confrontation in June 2020 or the India-China Standoff at Galwan, which would fall between the second and first quadrants, respectively.

4.2.1 Activities in the Irregular Warfare Quadrant

China has resorted to cyber espionage and intelligence gathering against the US. The Digital Silk Route - 5G cyber operations have targeted U.S. government entities, personnel, allies, and defence contracting companies.58 Along India’s northern borders, close to the Line of Actual Control (LAC), dual-use settlements and infrastructure development was carried out under the Xiaokang villages initiative. This involved development of 628 villages (427 first line and 201 second line villages) in Tibet along the Indian border. The scale of the initiative involved establishing 62,160 households aimed at ‘border cohesion and border security’, presumably to bolster its border area territorial claims.59 Frequent assertions have also been made regarding territorial claims over disputed territories with India, especially in Arunachal Pradesh. Chinese survey vessels are frequently positioned near Indian territorial waters to gather Technical Intelligence ( TECHINT).

4.2.2 Activities in the Competition Quadrant

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), coercive acquisition of intellectual property (IP), Government stakes in critical infra companies, and Industrial espionage have all been identified as China’s economic coercion tools. For instance, China cut off Japanese access to rare earth metals in the midst of an unrelated 2010 maritime dispute. Similar curbs on rare-earth metal exports are likely to impact Apple’s manufacturing operations in India.60

4.2.3 Activities in Deterrence Quadrant

China frequently tests the technologies needed to develop a co-orbital anti-satellite weapon, rendezvous (RV), proximity Operations, laser dazzling, etc., for space sector deterrence.61 China also actively cooperates, collaborates, and colludes with Pakistan. China’s ISR support to Pakistan during Operation Sindoor and military hardware supplies to Pakistan have already been highlighted. PLAAF and Pakistan Air Force (PAF) have also been carrying out the Shaheen series of combat exercises since 2011.

4.2.4 Activities in Regular Warfare Quadrant

The clash at Galwan on 15 June 2020 led to enhanced troop deployment and alteration of patrolling norms/ practices along the LAC, particularly in Eastern Ladakh. PLA occupied tactically advantageous positions and imposed restrictions on the movement of Indian patrols in the areas at Depsang plains (PPs10, 11, 11A, 12, and 13), Galwan, the north and south banks of Pangong Tso, PP-17 A, and PP-15 (Gogra-Hot springs area). China continues to maintain an active troop deployment along the northern borders with India, including mechanised formations, air defence assets, and artillery and infantry. Apart from the disengagement at the tactical level, the status quo has discernibly changed at the operational/ strategic levels.

Over thirty-one years, from the signing of the ‘Peace and Tranquillity Agreement’ in Sep 1993 to the subsequent Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) of Nov 1996, arrived at in the backdrop of the Sumdrong Chu incident of 1986-87, the provisions have been chipped away one incident at a time, such as stand-offs at Depsang and Chumar (2013-14), Dokala (2017), and Galwan (2020). This is an example of the classic Chinese long game at play.

The Grey Zone toolkits employed by China and Pakistan indicate the deft leveraging of this operational space to shape the environment towards its strategic objectives. It also exemplifies the funnel test attributes.5 Conclusion

Policy makers and analysts face challenges in assessing, profiling, and countering threats in the Grey Zone. This challenge arises from their inability to weigh these threats against a set of determinants to profile them affirmatively and plan and coordinate countermeasures.

The discussion document analyses the Grey Zone from an operational space perspective, using a four-quadrant model based on an intersection of the Peace-War and Direct-Indirect action axes. Multidomain threats in the Grey Zone, involving all dimensions of power, simultaneously manifest in the four quadrants—regular warfare, irregular warfare, competition, and deterrence—as tools of contestation between states and non-state actors.

The above model was used to validate the definition of Grey Zone as an overarching operational space of coercive struggles between actors (state and non-state) across multiple domains, below the threshold of war, aimed at shaping the environment to achieve geopolitical objectives.

Threats in the Grey Zone are characterised by tactical clarity in execution. This clear tactical level execution is done while retaining strategic ambiguity about the intended objectives of the tactical action, which causes decision dilemma in the minds of the institutional and national leadership of the target state.

This definition was tested for activities between India, Pakistan, and China over a short window (between 2020 and 2025) across the four quadrants. This highlighted the four determinants of the Grey Zone: gradualism, escalation management, selective attributability, and tactical clarity with strategic ambiguity.

The analytical framework proposed in this document along with the funnel test can be effectively used by security analysists to identify and evaluate trajectories of emerging Grey Zone threats.

Further study is required to analyse the inherent limitations of structures within the state’s security architecture in diagnosing Grey Zone threats in a timely manner and calibrating its response.

Appendix A

Multi-Domain Grey Zone Activity Matrix : Pakistan, China & India

Footnotes

Sabharwal, Mukesh. ‘Ideological Aspects Of Grey Zone Warfare’. CENJOWS Journal, no. Feb 2020 (n.d.).↩︎

Gray, Colin S. Another Bloody Century: Future Warfare. Paperback ed. A Phoenix Paperback. London: Phoenix, 2006.↩︎

Atlantic Conference. ‘Today’s Wars Are Fought in the “Gray Zone.” Here’s Everything You Need to Know about It.’, 23 February 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/todays-wars-are-fought-in-the-gray-zone-heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-it/.↩︎

Financial Express Online. ‘What Is BAT, Pakistan’s Barbaric Border Action Team: All You Need to Know’. 22 June 2017. https://www.financialexpress.com/india-news/what-is-pakistans-barbaric-bat-border-action-team-all-you-need-to-know/650264/.↩︎

Sze-Fung Lee. ‘Decoding Beijing’s Gray Zone Tactics: China Coast Guard Activities and the Redefinition of Conflict in the Taiwan Strait’. Global Taiwan Brief, n.d. https://globaltaiwan.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GTB-Volume-9-Issue-6.pdf↩︎

Harikumar R, Foreword, Grey Zone Warfare in Indian Context, CENJOWS Journal, February, 2020.↩︎

Singh, Dushyant. Grey Zone Warfare: Way Ahead for India. New Delhi, India: Vij Books, 2023.↩︎

Hicks, Kathleen. By Other Means Part II: Adapting to Compete in the Gray Zone. 1st ed. CSIS Reports. Blue Ridge Summit: Centre for Strategic & International Studies, 2019.↩︎

Air Marshal B.K. Pandey (Retd). ‘Special Operations in Myanmar’. SP Guides Publications SP’s Land Forces (June 2015). https://www.spslandforces.com/experts-speak/?id=35.↩︎

Peter Dobias, and Kyle Christensen. ‘The “Grey Zone” and Hybrid Activities’. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, no. 2 (2022): 41-54 (2022).↩︎

Land Warfare Doctrine, 2018, Indian Army.↩︎

Joint Doctrine Publication 0-01 UK Defence Doctrine. 6th Edition. Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, Ministry of Defence, 2022. http://www.gov.uk/mod/dcdc.↩︎

Joint Doctrine Publication 0-01 UK Defence Doctrine. 6th Edition. Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre, Ministry of Defence, 2022. http://www.gov.uk/mod/dcdc.↩︎

Clausewitz, General Carl von, Col JJ Translated by Graham, and “New and Revised Edition with an introduction and notes by Col F.N. Maude C.B. (LATE R.E.)”. On War. First Edition. Vol. 1, 1874. https://books.apple.com/in/book/on-war-volume-1/id505988717.↩︎

Nils Petter Gleditsch, et al. “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research, Sage Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi), vol. 39, no. 5, 2002, pp. 615–37, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022343302039005007#:~:text=Measures%20of%20Armed%20Conflict%20The%20COW%20project,covered%20only%20the%20post%2D%20Cold%20War%20period.↩︎

Ibid. Minor Armed Conflict: at least 25 battle-related deaths per year and fewer than 1,000 battle-related deaths during the course of the conflict. Intermediate Armed Conflict: at least 25 battle-related deaths per year and an accumulated total of at least 1,000 deaths, but fewer than 1,000 in any given year.War: at least 1,000 battle-related deaths per year.↩︎

Clausewitz, General Carl von, Col JJ Translated by Graham, and “New and Revised Edition with an introduction and notes by Col F.N. Maude C.B. (LATE R.E.)”. On War. First Edition. Vol. 1, 1874. https://books.apple.com/in/book/on-war-volume-1/id505988717.↩︎

Robinson, Eric. ‘The Missing, Irregular Half of Great Power Competition’. Modern War Institute, West Point, 9 August 2020. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/the-missing-irregular-half-of-great-power-competition/.↩︎

Burrell, Robert S. ‘Understanding Gray Zone Conflict and Hybrid Warfare’. Irregular Warfare Initiative, 14 March 2023. https://irregularwarfare.org/articles/a-full-spectrum-of-conflict-design-how-doctrine-should-embrace-irregular-warfare/.↩︎

Times Now Digital. ‘Narco-Terrorism: What Is It and How Is India Tackling the Menace?’ 18 September 2019. https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/narco-terrorism-what-is-it-and-how-india-is-tackling-the-menace/490508.↩︎

Anushka Sharma. ‘Chronicle of Conflict- The India China Border Dispute from 1954- 2024.’ CNBC TV18, 21 October 2024. https://www.cnbctv18.com/india/chronicle-of-conflict-the-india-china-border-dispute-from-1950-to-2024-19496332.htm.↩︎

Anushka Sharma. ‘Chronicle of Conflict- The India China Border Dispute from 1954- 2024.’ CNBC TV18, 21 October 2024. https://www.cnbctv18.com/india/chronicle-of-conflict-the-india-china-border-dispute-from-1950-to-2024-19496332.htm.↩︎

Michael J. Mazarr. ‘Understanding Deterrence.’ 2018. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.↩︎

Michael J. Mazarr. ‘Understanding Deterrence.’ 2018. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.↩︎

Michael J. Mazarr. ‘Understanding Deterrence.’ 2018. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.↩︎

Lindsay, Jon R., and Erik Gartzke, eds. Cross-Domain Deterrence: Strategy in an Era of Complexity. Oxford University Press, 2019.↩︎

‘Minutes Cabinet Committee On Security Reviews Progress in Operationalising India’s Nuclear Doctrine’. Press Information Bureau, India, 4 January 2023. https://archive.pib.gov.in/release02/lyr2003/rjan2003/04012003/r040120033.html.↩︎

Lindsay, Jon R., and Erik Gartzke, eds. Cross-Domain Deterrence: Strategy in an Era of Complexity. Oxford University Press, 2019.↩︎

RS Panwar. ‘Towards an Effective and Viable Information Warfare Structure for the Indian Armed Forces’. UNITED SERVICE INSTITUTION OF INDIA, no. 16th Major General Samir Sinha Memorial Lecture, 2018 (n.d.). https://www.usiofindia.org/publication-journal/towards-an-effective-and-viable-information-warfare-structure-for-the-indian-armed-forces.html. Hicks, K. By Other Means Part II: Adapting to Compete in the Gray Zone, 1st ed.; CSIS Reports; Centre for Strategic & International Studies: Blue Ridge Summit, 2019.↩︎

Hicks, K. By Other Means Part II: Adapting to Compete in the Gray Zone, 1st ed.; CSIS Reports; Centre for Strategic & International Studies: Blue Ridge Summit, 2019.↩︎

Dolman, E. C. Pure Strategy: Power and Principle in the Space and Information Age; Cass series–strategy and history; Frank Cass: London; New York,2005.↩︎

Sabharwal, Mukesh. “Ideological Aspects Of Grey Zone Warfare. Synergy Journal, CENJOWS, February 2020.↩︎

Ajay Kumar. ‘Pakistan’s Perception And Responses Towards The Cold Start Doctrine’ Vol 58. No.3 (2021) (18 November 2020). http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/4488/3948.↩︎

Harsh Vardhan Singh. ‘Evolution of Warfighting Strategy in India’. CENTRE FOR LAND I WARFARE STUDIES (CLAWS), 22 October 2020. https://www.claws.in/evolution-of-warfighting-strategy-in-india/.↩︎

Ajay Kumar. ‘Pakistan’s Perception And Responses Towards The Cold Start Doctrine’ Vol 58. No.3 (2021) (18 November 2020). http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/4488/3948.↩︎

Ajay Kumar. ‘Pakistan’s Perception And Responses Towards The Cold Start Doctrine’ Vol 58. No.3 (2021) (18 November 2020). http://psychologyandeducation.net/pae/index.php/pae/article/view/4488/3948.↩︎

General Naravane’s comments summarised by Kanchana Ramanujam, Col Anuraag Singh Rawat, SM, and Dr.Jyoti M Pathania. ‘Pragyan Conclave 2020 Changing Characteristics of Land Warfare and Its Impact on the Military’. CLAWS, 4 March 2020. https://www.claws.in/static/SR_PRAGYAN-CONCLAVE-2020.pdf.↩︎

Platoons of Infantry Battalions of IA trained in Commando tactics.↩︎

Deependra Singh Hooda, Zhang Li, Brig. Imran Hassan, and Lisa Curtis. ‘Regional Roundtable: Reflections on Balakot’. The Stimson Centre, n.d. https://www.stimson.org/2022/three-years-after-balakot-reckoning-with-two-claims-of-victory/.↩︎

Deependra Singh Hooda, Zhang Li, Brig. Imran Hassan, and Lisa Curtis. ‘Regional Roundtable: Reflections on Balakot’. The Stimson Centre, n.d. https://www.stimson.org/2022/three-years-after-balakot-reckoning-with-two-claims-of-victory/.↩︎

Atlantic Conference. ‘Today’s Wars Are Fought in the “Gray Zone.” Here’s Everything You Need to Know about It.’, 23 February 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/todays-wars-are-fought-in-the-gray-zone-heres-everything-you-need-to-know-about-it/.↩︎

Madiha Afzal. Pakistan’s Surprising and Marred 2024 Election, and What Comes Next. Brookings. February 29, 2024. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/pakistans-surprising-and-marred-2024-election-and-what-comes-next/.↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024.↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024↩︎

Bisaria, A. Anger Management: The Troubled Diplomatic Relationship between India and Pakistan; Aleph Book Company: New Delhi, 2024↩︎

Saurabh Trivedi. China Used Conflict between India and Pakistan as a Live Lab: Deputy Chief of Army Staff. The Hindu. New Delhi July 10, 2025. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/deputy-chief-of-army-staff-capability-development-and-sustenance-lieutenant-general-rahul-r-singh-on-operation-sindoor/article69772121.ece.↩︎

Imran Khan. ‘Statement by the Prime Minister of Pakistan H.E. Imran Khan to the Seventy-Sixth Session of the UN General Assembly’. UNGA, 24 September 2021. https://estatements.unmeetings.org/estatements/10.0010/20210924/ajen3uMeQSDH/XOqp89IAVee9_en.pdf.↩︎

Reuters. ‘Pakistan PM Calls Meeting of Body That Oversees Nuclear Arsenal, Says Pakistan Military’. 10 May 2025. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/pakistan-pm-calls-meeting-body-that-oversees-nuclear-arsenal-says-pakistan-2025-05-10/.↩︎

Economic Times Online. ‘Stealth Jets, Submarines & Missiles: Is China Giving Pakistan the Edge over India in the Growing Arms Race?’ 22 March 2025.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/stealth-jets-submarines-missiles-is-china-giving-pakistan-the-edge-over-india-in-the-growing-arms-race/articleshow/119299754.cms?from=mdr#.↩︎

Guoguang Wu. ‘Xi Jinping’s Purges Have Escalated. Here’s Why They Are Unlikely to Stop’. Asia Society Policy Institute, 26 February 2025. https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/xi-jinpings-purges-have-escalated-heres-why-they-are-unlikely-stop.↩︎

Aleksandra Gadzala Tirziu. ‘China’s Military Expansion: A Global Power Shift in the Making’. GIS, 16 December 2024. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-military-expansion/.↩︎

‘China Economic Update June 2025’. World Bank Publications, June 2025. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/8ae5ce818673952a85fee1ee57c3e933-0070012025/original/CEU-June-2025-EN.pdf.↩︎

Roderick Lee, and Marcus Clay. ‘Don’t Call It a Gray Zone: China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum’. War on the Rocks, 9 May 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/05/dont-call-it-a-gray-zone-chinas-use-of-force-spectrum/.↩︎

Roderick Lee, and Marcus Clay. ‘Don’t Call It a Gray Zone: China’s Use-of-Force Spectrum’. War on the Rocks, 9 May 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/05/dont-call-it-a-gray-zone-chinas-use-of-force-spectrum/.↩︎

Hicks, Kathleen. By Other Means Part II: Adapting to Compete in the Gray Zone. 1st ed. With Melissa Dalton. CSIS Reports. Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2019.↩︎

Vivek Singh. ‘China’s Infrastructure Development Along The Line Of Actual Control (LAC) and Implications for India’. CENJOWS, 29 January 2024. https://cenjows.in/chinas-infrastructure-development-along-the-line-of-actual-control-lac-and-implications-for-india/.↩︎

The Times of India. ‘China’s Rare Earth Export Curbs Hit Another Industry! Apple AirPods Production at Foxconn India Unit Faces Hurdles; Here’s What’s Happening’. 22 July 2025. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/chinas-rare-earth-export-curbs-hit-another-industry-apple-airpods-production-at-foxconn-india-unit-faces-hurdles-heres-whats-happening/articleshowprint/122829069.cms.↩︎

Hicks, Kathleen H. By Other Means Part I: Campaigning in the Gray Zone. 1st ed. With Alice Hunt Friend. CSIS Reports. Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2019.↩︎

Ayjaz Wani. ‘TRF Designated: Still Challenges Remain in Kashmir’s Counter-Terrorism Campaign’. ORF, 21 July 2025. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/trf-designated-still-challenges-remain-in-kashmir-s-counter-terrorism-campaign.↩︎

Hannah Ellis-Petersen, Aakash Hassan and Shah Meer Baloch. ‘Indian Government Ordered Killings in Pakistan, Intelligence Officials Claim’. The Guardian, 4 April 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/04/indian-government-assassination-allegations-pakistan-intelligence-officials.↩︎

Vinod Khandare.‘Debate with Arnab’. 4 June 2025. Television. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QM5F5pkOu-I.↩︎

Claude Arpi.‘The Ladakh Confrontation’. 2020. https://www.voatibetan.com/a/the-ladakh-confrontation/6758839.html.↩︎