The FY 2027 Defence Budget Must Bridge the Gap Between ‘Aatmanirbharta’ and Reality

Authors

As the Indian Ministry of Defence prepares to present its demands in the upcoming fiscal year’s budget, the narrative surrounding India’s military modernisation is one of ambitious intent clashing with stubborn structural realities. The reports from the 18th Lok Sabha’s Standing Committee on Defence on the 2024-26 budgets serve as a critical mirror, reflecting not just where the money is going but also where the government machinery is stalling.

While the Budget Estimate (BE) for 2025-26 showed a robust increase to ₹6.81 lakh crore, a deeper dive into the Committee’s observations reveals that the FY 2027 budget cannot simply be about more money. It must address the disconnect between policy announcements and on-the-ground execution.

The Context

Throughout 2025, the security dynamics on India’s western frontier deteriorated sharply, culminating in the mobilisation and engagement under ‘Operation Sindoor’. Unlike previous standoffs, which were primarily artillery or infantry-driven, Operation Sindoor was characterised by the intensive use of new war technologies: loitering munitions, swarm drones, and precision-guided missiles.

While the western front provided the kinetic trigger in 2025, the northern front remains the strategic anchor of India’s defence planning. The Standing Committee on Defence has repeatedly warned in its reports that the collusive threat from Pakistan and China is no longer a theoretical construct but an operational reality.

Teeth-to-Tail Imbalance

The Committee cited the 15th Finance Commission and earlier expert bodies to argue that 3% of the GDP is the minimum defence budget required to modernise a force with a 60% vintage inventory. In the past two years, the average has stayed below 2% of GDP.

But the most glaring warning from the Committee is the persistent imbalance between Revenue and Capital expenditure. Currently, the ratio is roughly 63:37, meaning that for every rupee spent, 63 paise goes toward salaries, pensions, and maintenance, leaving only 37 paise for modernisation and new assets.

Capital outlay expenditure, estimated at around ₹1,80,000 cr in FY 2026 BE stage, is the heart and soul of military modernisation. This is the money spent for acquiring new and advanced defence technologies and equipment. At a time when Chinese and Pakistani aggression in both continental and maritime theaters around us continues to escalate, capital expenditure on must-have platforms has the potential to determine the confidence of India’s response to the ‘China challenge’.

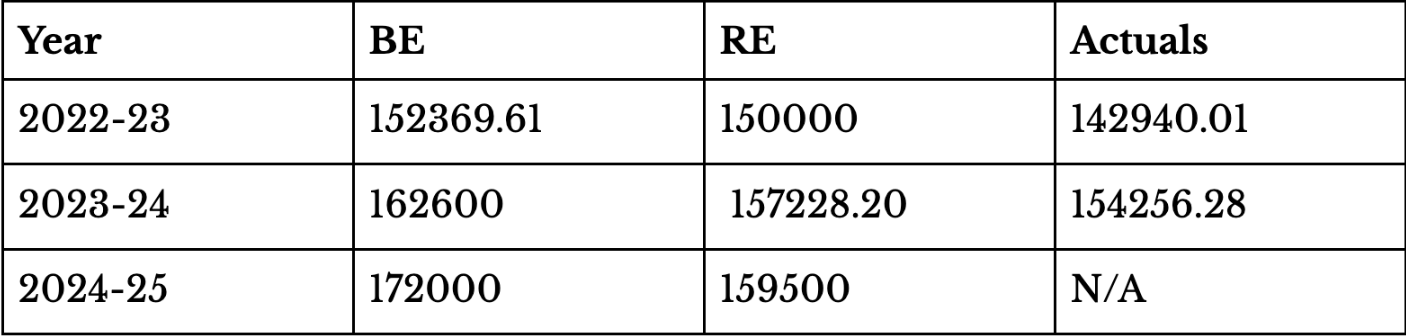

The estimated capital outlay for FY 2025-26 is hiked by a mere 4.6% as compared to the FY 2024-25 BE. As compared to the RE for FY 2024-25, the hike is at 12.8%. However, trends of capital outlay over the past few years indicate that the BE is always higher than the Revised Estimate (RE), while the RE is always higher than the actuals.

While the Government has argued that rectifying this immediately is not feasible due to committed liabilities, the Committee has rightly flagged this as a strategic vulnerability. A modern military cannot run on a budget that prioritises sustenance over substance. Hence, the FY 2027 budget must demonstrate a tangible roadmap to shift this trajectory, ensuring that the ‘Capital Outlay’ component is not just nominally increased, but structurally prioritised to fund the expensive realities of modern warfare.

In this regard, the Committee has also taken a serious view of the MoD’s tendency to surrender funds at the end of the fiscal year. In the RE for 2024-25, the capital outlay was revised downward to ₹1,59,500 crore from a BE of ₹1,72,000 crore, implying a surrender of nearly ₹12,500- ₹13,500 crore.

In its Action Taken Note (ATN), the MoD argued that the surrender is technical rather than actual. The Ministry noted that while cash outgo was lower, the value of contracts signed reached an all-time high of ₹1.82 lakh crore by December 2025. The lag is due to payment milestones, i.e. contracts signed late in the fiscal year (such as the DAC approvals on December 29, 2025) involve only small advance payments, pushing the bulk of the expenditure to subsequent years.

Nonetheless, a key aspect, as even the committee has highlighted, is that insisting that committed liabilities are used as an excuse for not fully consuming the modernisation budget. A non-lapsable, roll-on fund for defence modernisation may be a useful tool in this regard, but again, a Secretary of the Finance Ministry has argued in the Committee’s 2023-24 report that there was no need for such a fund to guarantee continued progress in military modernisation. This was so because the budget allocation process had now become more consultative, involving representatives from the armed forces.

Float Without Fight?

Nowhere is the gap between procurement and capability more visible than in the service-specific analysis. The Committee noted that while the Navy has successfully indigenised the “Float” (hulls) and “Move” (propulsion) components of its fleet, the “Fight” component – weapons and sensors – remains dangerously dependent on imports.

Similarly, the Army saw a 4.49% decline in its capital allocation in 2024-25. The Ministry’s defence, that Army gear is less expensive” than jets or ships, rings hollow when viewed against the urgent need for drones, counter-drone systems, and surveillance tech along the Northern borders. The FY 2027 budget must correct this dip; low-cost warfare does not imply low-priority funding.

During Operation Sindoor, the ubiquity of low-cost aerial threats became apparent. The Standing Committee has noted that while macro air defence (S-400, MR-SAM) is robust, the micro air defence against small, slow-moving drones remains a work in progress. This realisation is the direct driver behind the DAC’s December 2025 approval for the Integrated Drone Detection & Interdiction System (IDDIS) Mk-II and Low Level Light Weight Radars (LLLWR) under the Emergency Procurement (EP) mechanism.

While the legacy of Operation Sindoor is the institutionalisation of the EP mechanism, the Standing Committee, in its review of the 2025-26 expenditures, has observed that EP routes often bypass the rigorous standardisation and lifecycle cost analysis of the DAP. However, given the operational urgency, the Committee has largely supported these outlays, provided they lead to tangible improvements in capability. The FY 2027 budget is expected to regularise some of these emergency purchases into long-term sustainment contracts, particularly for loiter munitions and tactical surveillance drones, moving them from the ad-hoc ledger to the planned modernisation ledger.

Modernisation at the Speed of Bureaucracy

The Committee has also taken aim at the procurement timeline, which currently ranges from 74 to 106 weeks (nearly two years) from request to contract. In an era where technology evolves in months, a two-year delay ensures the military is inducted into obsolescence.

While the Ministry claims to have issued “Guidelines for Compressing Timelines,” the Committee remains sceptical, noting a lack of evidence that these guidelines have actually reduced delays. For FY 2027, the focus must shift from issuing guidelines to enforcing penalties. A combination of a “do” and “don’t” – enforcing strict timelines and punishing vendors who delay offsets, while putting a halt to endless revisions of the Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) that create policy churn without outcome – is to look forward to in defence policy going ahead.

The R&D Imperative

Finally, the budget must address the future. With DRDO receiving only ~5.38% of the total defence budget, the Committee’s demand to raise this to 10% is not just a wish, but a necessity for a nation aspiring to be a global power. While the Government has approved a ₹500 crore corpus for Deep Tech, the scale of investment pales in comparison to the adversarial strides in AI and hypersonics made, for example, by China.

The FY 2027 Defence Budget will likely be celebrated for its headline figures. However, the Parliamentary Standing Committee has provided the blueprint for what actually matters – execution. As one looks ahead to the upcoming budget, the question is not whether India can afford to spend more on defence, but whether it can afford the cost of bureaucratic lethargy.

Acknowledgements: The author is grateful to Pranay Kotasthane for his research guidance and consistent data retention endeavours.

Disclaimer: 2025-26 RE & Actuals, as well as 2026-27 BE are awaited.