India maintains strict control over its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), reserving fishing solely for Indian-flagged vessels. Despite this, persistent Automatic Identification System (AIS) data reveal a continued presence of Sri Lankan and Chinese vessels operating within the EEZ. These intrusions result in economic loss, ecological exploitation, and most importantly, raise the risk of maritime surveillance by foreign actors. Illegal fishing contributes to resource depletion, threatens coastal livelihoods and, when involving vessels linked to foreign governments, creates avenues for grey-zone maritime operations.

In November 2025, the Government of India updated its regulations for fishing in the EEZ. The foundation of this policy is the Maritime Zones of India Act, 1981, which reserves the EEZ for Indian vessels unless explicit permission is granted by the Union Government. The accompanying 1982 Rules operationalise this ban and set strict conditions for any foreign access — permissions that India almost never grants. Enforcement has been further modernised through the REALcraft (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Licensing for craft) system, which digitally verifies vessel identity, crew and catch records. REALcraft integrates AIS and Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) data for real-time monitoring, ensuring traceability of fishing voyages and automatically flagging unauthorised entries.

Despite these strict regulations, AIS-recorded fishing activity by Sri Lankan and Chinese vessels continues. India has no bilateral arrangement granting Sri Lankan vessels the right to fish in India’s EEZ; all historical reciprocal rights were terminated under the 1974 Katchatheevu and 1976 Maritime Boundary Agreements.

China’s Distant-Water Fleet (DWF) — the world’s largest, backed by heavy state subsidies — is directly prohibited under Indian rules. Although India does not explicitly name China in policy, the blanket ban fully applies. China’s DWF has been globally linked to dual-use operations, including oceanographic surveying, acoustic mapping and maritime domain intelligence. For India, this creates severe vulnerabilities: seabed mapping, submarine detection and long-term reconnaissance of naval spaces. The DWF often operates with advanced communications and navigation equipment with potential ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) value. For instance, four Chinese “research vessels” were deployed to the Indian Ocean soon after India announced a major missile test window for December 1–4, 2025 — a clear example of dual-use activity.

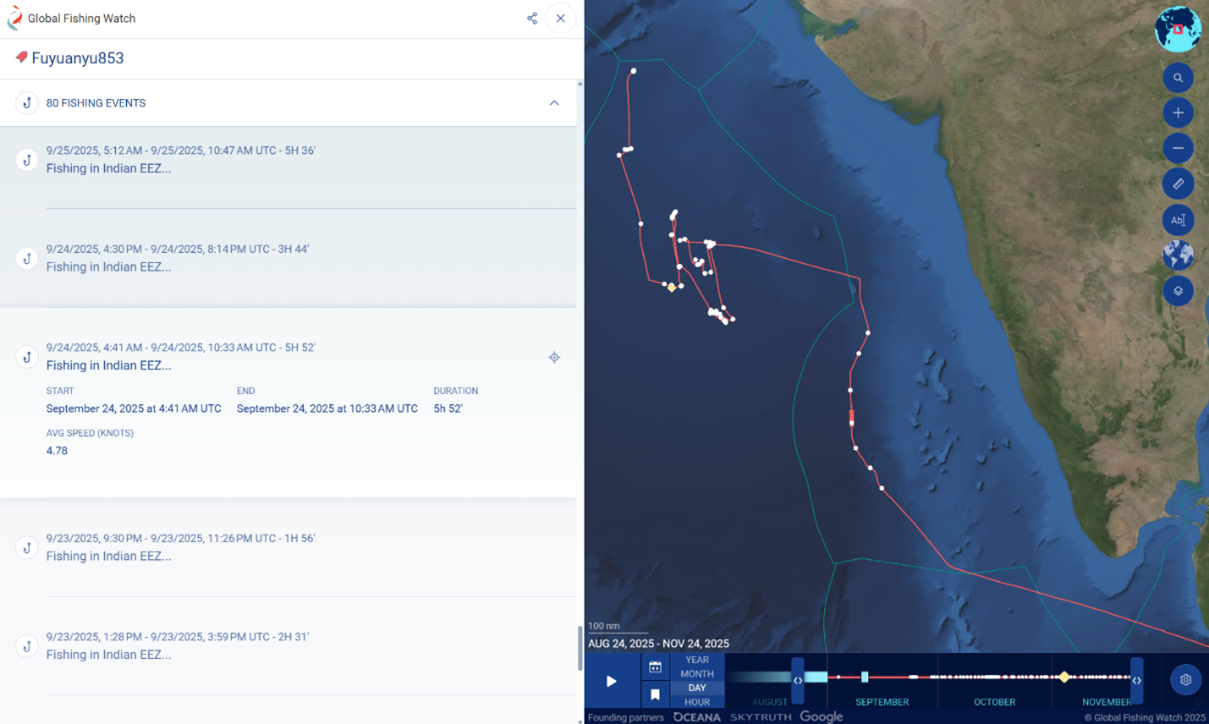

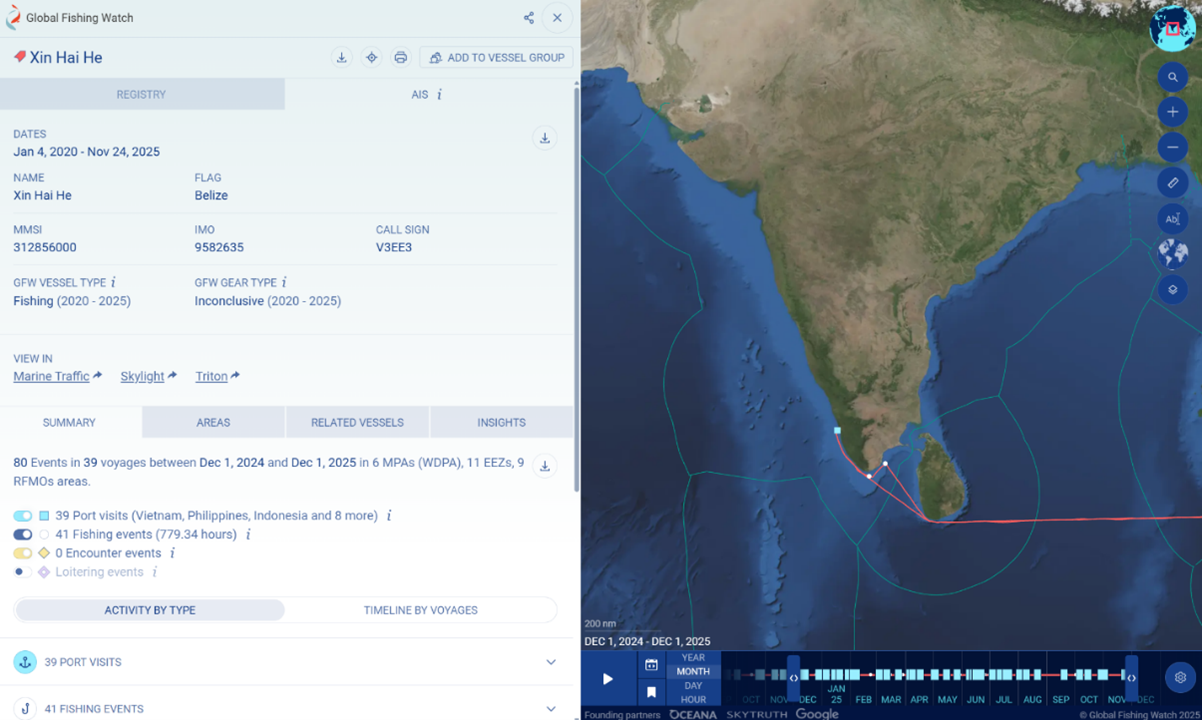

Global Fishing Watch (GFW) data highlights these trends. Vessels such as Imula 0784Mtr (Sri Lanka), Fuyanyu 853 (China) and Xin Hai He (Belize-flagged but operating from Chinese ports) exhibit looping, low-speed tracks that characterise squid jigging and trawling — typical DWF behaviour. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show their tracks within and near India’s EEZ boundary. Since AIS can be deliberately switched off, these visible detections likely represent only a fraction of actual incursions.

What The Data Shows

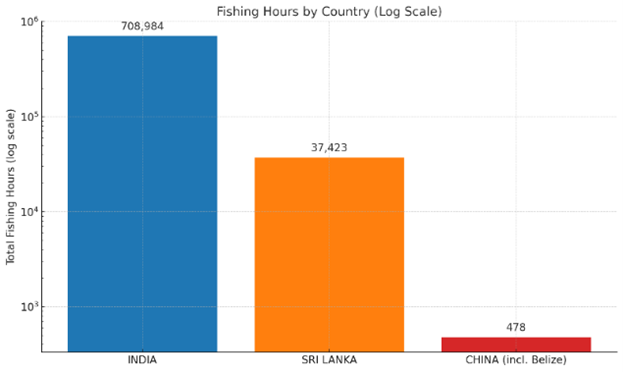

Figure 1. compares country-wise apparent fishing hours in India’s EEZ. Indian vessels dominate — as expected — but Sri Lankan vessels register over 37,000 hours, and Chinese-linked vessels (including Belize-flagged operators) show substantial presence despite the ban.

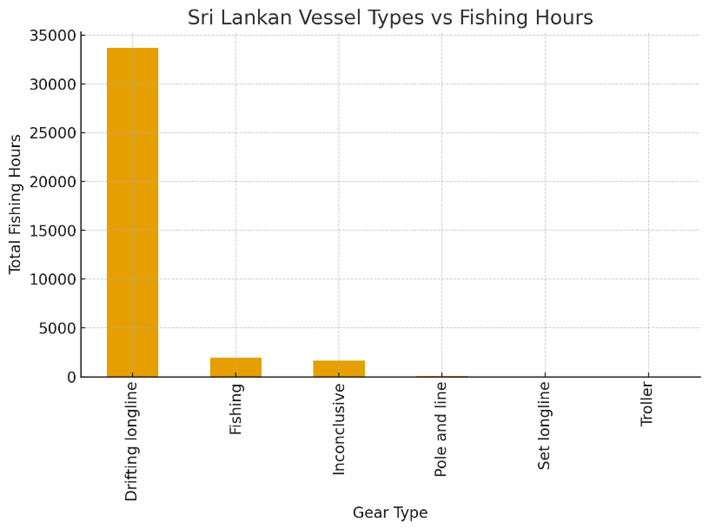

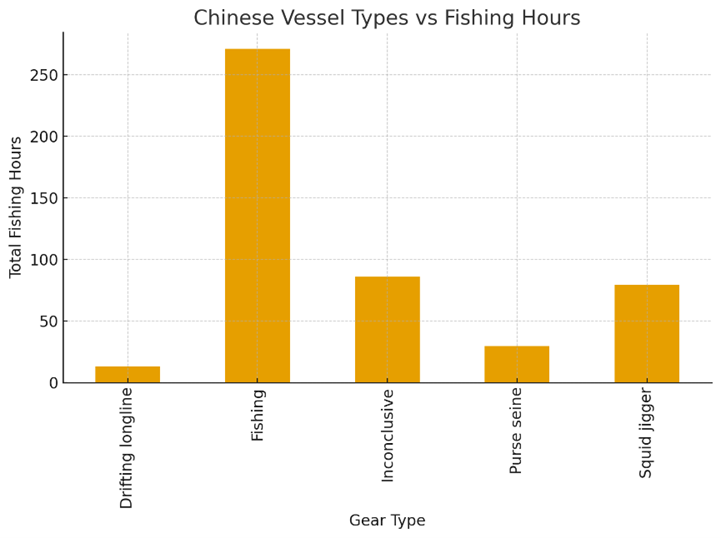

Figure 2 and Figure 3 break down gear types, with Sri Lankan vessels primarily using drifting longlines — a known method for tuna species — while Chinese vessels exhibit mixed behaviour including longlining, purse seine and squid fishing.

Primary Data source from Global Fishing Watch. Graphs made by Author.

Figure 4 shows the movement of a Chinese-flagged vessel Fuyanyu 853 over multiple fishing events recorded by GFW in 2025. The AIS track displays a looping; slow speed pattern concentrated well inside India’s EEZ. This movement signature is typical of active fishing behaviour.

Figure 5 shows the operational track of Xin Hai He, a Belize flagged vessel that never operates in Belize and instead sails from Chinese ports, strongly suggesting a flag-of-convenience profile. Such movements are characteristic of transit-cum-fishing behaviour, where vessels probe the EEZ perimeter and exploit areas that are harder to patrol.

To strengthen India’s maritime security posture, geospatial monitoring is critical. AIS-based geofencing can automatically alert the Indian Coast Guard when foreign vessels enter the EEZ. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites enable vessel detection even when AIS is disabled, though SAR-only detections risk false positives due to clutter and signal distortions. Therefore, multi-sensor fusion, SAR + AIS + VMS + Radio Frequency (RF) detection + optical imagery — produces reliable tracking. Software platforms such as Starboard already fuse these streams to highlight suspicious loitering or boundary-hugging patterns. Monthly heat maps and machine-learning behavioural analytics can help focus patrols on hotspots. Illegal fishing in India’s EEZ is not just a legal violation — it is a geospatially traceable threat with direct implications for sovereignty, resource security and national defence.