India Should Double Down on Rare Earth Recycling

Authors

Executive Summary

Tannmay is a Junior Adjunct Scholar associated with the High-Tech Geopolitics programme at the Takshashila Institution.

Rare earths are different from resources like oil because they can be recovered from discarded products. This paper argues that India’s fastest and least harmful path to partial supply security is through urban mining and domestic recycling rather than recreating a complete primary mining ecosystem.

Pranay is Deputy Director and chairs the High-Tech Geopolitics programme at the Takshashila Institution.

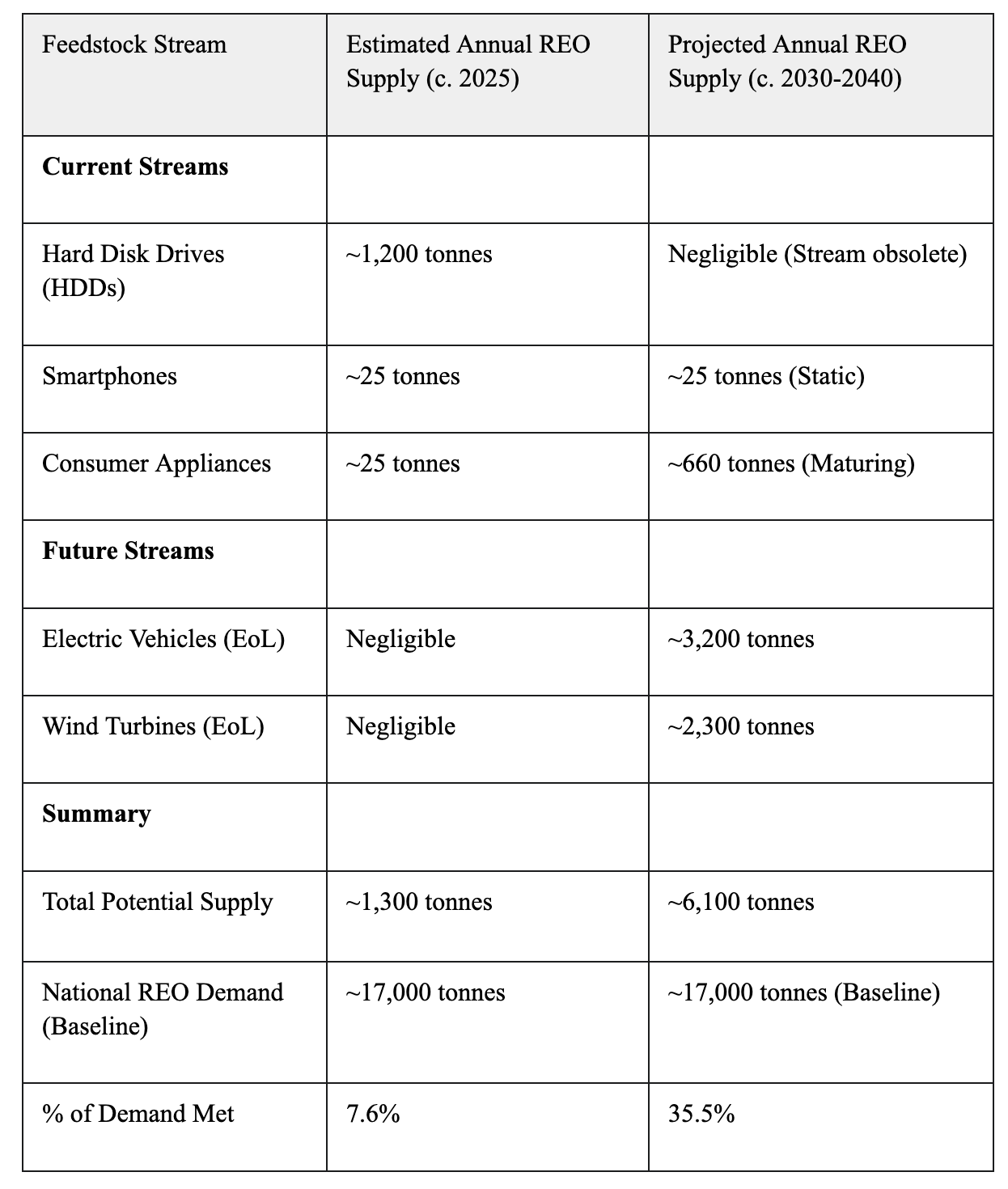

Urban mining turns India’s growing e-waste stream into a domestic source of rare earths. Today, this can supply around 1,300 tonnes of material each year, and this number could rise above 6,000 tonnes in the next decade as EVs, wind turbines and appliances reach end-of-life.

Narayan is a Co-Founder of the Takshashila Institution.

Recycling offers concentrated feedstock, lower environmental damage and a chance to formalise waste handling. India has not yet built this industry because current incentives reward weight instead of value, global markets are volatile, and government policies are fragmented.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Rahul Matthan for his invaluable comments and feedback.

This paper proposes a simple and coordinated path forward. India should classify rare-earth components as a high-value category under the e-waste rules. It should create a temporary price floor, or offtake guarantee, to make early plants viable. It should set up a domestic co-investment mechanism on the lines of an inward-facing version of KABIL (Khanji Bidesh India Limited). It should update the PLI (Production Linked Incentive) scheme for magnets to allow the use of recycled material. Finally, it should also open a regulated channel for importing sorted high-value scrap.

Introduction

China’s dominance was not a triumph of unique chemistry. Solvent extraction was developed in the West in the 1950s. China built its monopoly through economic coercion. It used state subsidies, predatory pricing, and a willingness to absorb environmental costs, not superior technology.

Rare Earth Elements (REEs) are a set of 17 elements which are critical to the modern economy. The unique magnetic properties of these elements make them ubiquitous in smartphones, EV motors, wind turbines, and advanced defence systems. This entire supply chain, however, is overwhelmingly dominated by a single player: China, which controls nearly 70% of the world’s mining and 90% of the global REE refining capacity.1 For more than two decades, Indian industries have sourced critical components—especially permanent magnets—almost entirely from China. Viable alternatives are not only scarce and prohibitively expensive—often 10 to 15 times the cost—but have also been historically dependent on China for their own raw materials, thus creating an inescapable dependency.

The 17 REEs include the 15 lanthanides plus Scandium and Yttrium.

This dominance is not a passive risk. China has increasingly demonstrated a willingness to weaponise this dependency by imposing export curbs to create leverage. This threat has brought forth the REE supply chain as one of the world’s most widely discussed supply chain security issues. In April 2025, China moved several medium and heavy rare earths and most magnet-grade materials into an export licensing regime.2 Shipments slowed sharply as exporters were required to file detailed end-use declarations with China’s Ministry of Commerce. For Indian firms, this created long delays and heavy paperwork. Importers now had to route applications through multiple Indian ministries, and also get documents verified by Chinese authorities. Around 500 to 600 Indian companies applied for these clearances. Only a very small number received conditional approvals, and even these came with narrow end-use limits—including restrictions on re-export and defence use.3 Even though China later eased parts of the process, the disruption made clear how exposed Indian industry remains when a single link in the rare-earth chain is tightened. The sudden imposition of these curbs sent ripples through multiple industries that use REEs, causing production delays, higher costs and lower efficiency—with some even forced to go rare-earth-free in their new products.

Sintering involves compressing powdered metal at high temperatures. It transforms loose REE powder into a solid, magnetised block.

Moreover, to shut down any potential workarounds, China has also restricted the export of “sintered blocks,” preventing Indian processors from importing semi-finished goods and developing finished products in India. With non-Chinese suppliers fully booked for years by US and Japanese buyers, the Indian industry is left with few viable options.

Stages of the Supply Chain

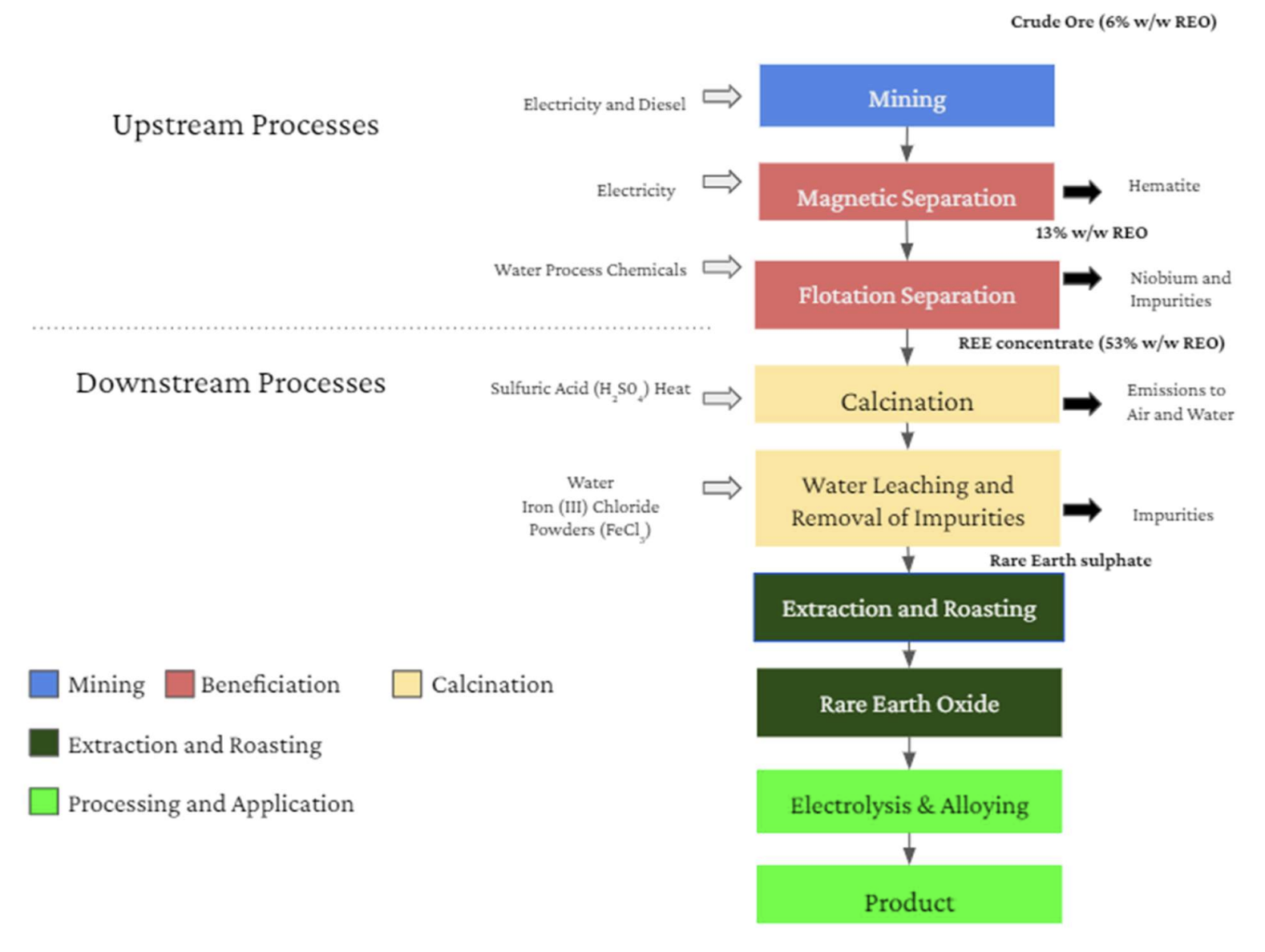

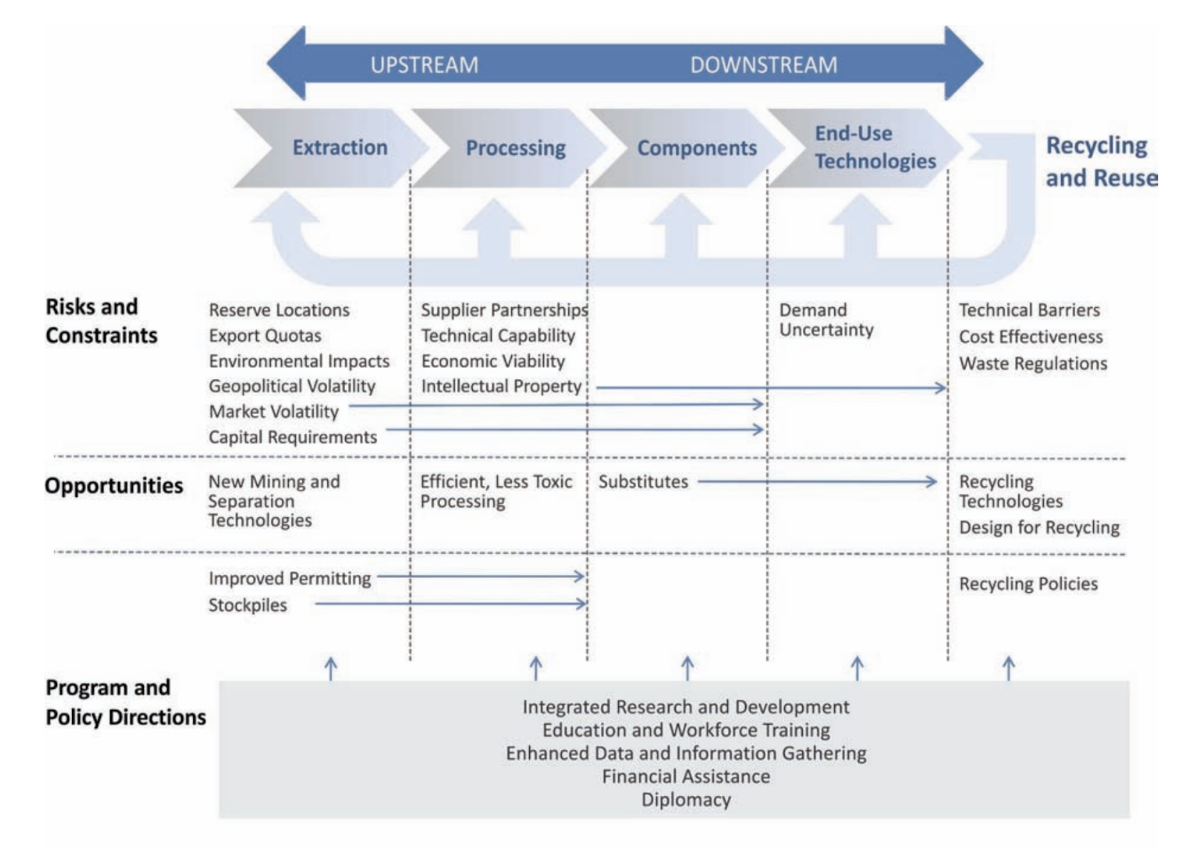

Understanding the rare-earth supply chain is important, as every stage has its own technical complexities and geopolitical risks. At the broadest level, the chain runs from first, extraction of raw minerals, to second, production of finished components, and finally to the technologies that use them. A growing ‘fourth stage’ circles back into the chain by recovering material from products that have reached the end of their life.

Source: A Rare-Earths Strategy for India, Takshashila Discussion Document, December 2020.4

Source: A Rare-Earths Strategy for India, Takshashila Discussion Document, December 2020.4

The word ‘rare’ was to imply brilliance as adding them to glass gave it radiant colours, and also owing to how difficult it was to extract them.5 However, geologically, REEs are actually quite common within the Earth’s crust. The rarest of REEs, Thulium, is 125x more common than gold, and the most common of REEs, Cerium, is 15,000x more common than gold.6

Mining: This is where ores such as Bastnaesite or Monazite are dug up and processed into a basic concentrate. REEs are actually quite commonly found within the Earth’s crust, and are not as rare as the name might suggest.7

Refining & Separation: This is the part that turns a mixed concentrate into individual rare-earth oxides. It is a chemical-intensive, slow, and costly process which is the main reason why only a few countries have meaningful midstream capacity. This is also the stage where China holds its strongest position.

A single 3 MW offshore wind turbine can contain up to 2 tonnes of rare earth magnets, which is roughly the same amount found in 2 million smartphones.

- Manufacturing: Here, the separated oxides are converted into metals and alloys, and subsequently shaped into high-value components. The most important of these are permanent magnets, which are used in electric motors, wind turbines, hard disk drives, and many other devices.

Source: Critical Minerals Strategy, US Department of Energy, 20208

Source: Critical Minerals Strategy, US Department of Energy, 20208

The fourth stage is recovery from end-of-life products. This stage has become increasingly important as countries seek alternatives to primary mining. Many products contain high concentrations of valuable material, especially magnets, which can hold 25–30 percent rare earths by weight.9 Recovering these materials and feeding them back into the supply chain can reduce the need for new mining, lower costs, and cut environmental damage.

India’s Vulnerability

Understanding this chain is key to India’s current position. The global industry is dominated not by who has the most ore—a lot of countries have large REE reserves10—but by who controls the midstream refining bottleneck. China’s near-total monopoly here effectively means that all rare-earth products have some Chinese-refined metal in them, which is what creates leverage.

India’s REE reserves are concentrated along the coastal sands of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Odisha. The typical oxide distribution in these monazite sands is about 45% cerium, 24% lanthanum, 17% neodymium and 5% praseodymium. Only trace amounts of the heavy rare earths that matter most for defence applications.

IREL was established in 1950, making it one of the world’s oldest rare earth enterprises. Yet it remains largely a relatively small scale miner.

India, on the other hand, despite having the world’s third-largest REE reserves—estimated at 6.9 million tonnes—has negligible domestic production.11 India’s total domestic production stands at a mere 2,900 tonnes12, of which state-owned Indian Rare Earths Limited (IREL) accounts for the majority. This, too, is a raw concentrate, exported to China for refining since there are no major refiners in India.

This was not China’s first use of REE leverage. In 2010, China informally blocked REE exports to Japan during the Senkaku Islands dispute. But the recent controls are different—they are officially declared, structured as retaliatory measures, and backed by a formal bureaucratic permit system. This permanence signals that China intends to use this tool again.

At the same time, India’s consumption is significantly larger, and rapidly growing. The country imported nearly 3,000 tonnes of rare-earth metal, and 53,000 tonnes of finished permanent magnets in 2024-25.13 The predominant source of these magnets (90%) was China. This over-reliance culminated in a crisis in 2025, when China announced export restrictions on certain REE products. Indian automotive and electronics manufacturers were suddenly faced with supply disruptions, and many had to consequently slow down production.

Having explained the strategic context, this document has four further sections. Section 2 outlines the idea of urban mining. Section 3 maps India’s current and future potential. Section 4 describes the barriers, and the last section presents the policy roadmap.

The Urban Mining Opportunity

The term “urban mining” was coined by Japanese researcher Hideo Nanjo in 1988. Japan, resource-poor but e-waste-rich, pioneered the concept after the 2010 China embargo forced it to find alternatives.

Given India’s current dependency on rare-earth imports, developing an alternative supply chain is a priority. The most viable path forward is not to replicate China’s decades-long, environmentally costly primary production model. A leapfrog opportunity exists herein: India can build a circular model from the ground up by developing a robust domestic recycling industry. This approach, known as urban mining, would reframe the nation’s growing stream of electronic waste as a rich, indigenous, and continuously replenishing mineral resource.

What is Urban Mining?

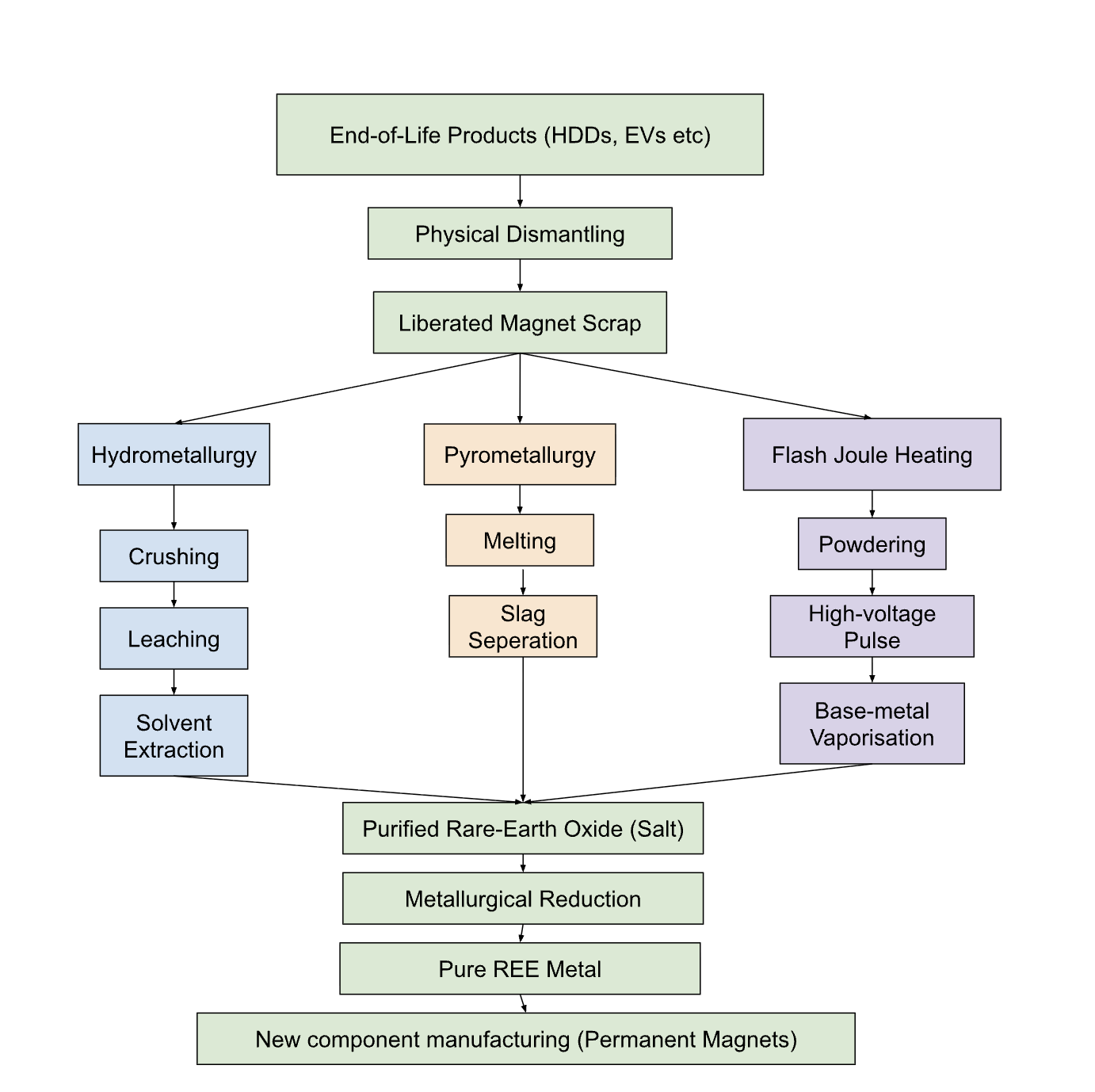

Urban mining is, quite simply, the recovery and reprocessing of REEs from end-of-life products. It focuses on mining anthropogenic deposits—namely our discarded electronics—rather than geological ore.14 In practice, this is a technically complex undertaking for several reasons.

NdFeB magnets are the strongest permanent magnets known. A small one can lift over 1,000 times its own weight.

First, REEs are embedded in complex products, often as small, alloyed components such as NdFeB (Neodymium Iron Boron) magnets. These parts are often coated, glued or press-fit into housings. Trying to pull them out by hand is a slow process, and can break the magnet or the part. Shredding or hammering frees the magnets quickly but mixes them with steel, plastics and dust, which raises sorting costs and creates contamination that makes chemical processing harder.15

Second, even after a component is liberated, the alloy itself must be chemically broken down. Chemical separation is required to distinguish valuable REEs (like Neodymium) from bulk materials (like iron), a process that must sever strong metallic and intermetallic bonds.16

Third, the feedstock itself is diffuse. A single magnet is highly concentrated (25-30 percent REE by mass), but the overall e-waste stream is not; it requires sophisticated sorting and collection to gather enough scrap to be economical.

Several technical pathways exist to recover REEs from scrap. The three main approaches are Hydrometallurgy, Pyrometallurgy, and newer Thermal-electrical methods.

The acids used in hydrometallurgy—typically hydrochloric or nitric—are the same ones used in primary mining. The chemistry is similar; only the feedstock differs.

Hydrometallurgy: This is the closest analogue to mining chemistry. Scrap is first mechanically prepared, and the magnetic material liberated. The powder, or shredded material, is then treated with acids to dissolve the metals into an aqueous solution (leaching). The dissolved rare-earth ions are separated from other dissolved metals using solvent extraction, or by causing them to form solids (precipitation). In solvent extraction, a tailored organic solvent selectively binds REE ions and transfers them into a separate liquid phase. In precipitation, chemicals are added to the solution so that REE salts fall out as solids that can be filtered and washed. Hydrometallurgy can recover more than 90% of REEs from suitably prepared feedstock. Its downsides are high water and acid use, the need for corrosion-resistant equipment, and the generation of hazardous liquid wastes that require treatment and disposal.17

Pyrometallurgy: This route heats scrap to high temperatures in furnaces or smelters. Under these conditions, different elements separate by melting point, vapour pressure or oxidation behaviour. Smelting and slagging can concentrate REEs into a residue for further processing. Pyrometallurgy avoids large volumes of liquid waste, and can be robust against contaminated feedstock. However, it is a very energy intensive process, which can lose volatile REE fractions if not tightly controlled, and usually gives lower separation precision than hydrometallurgy.18

Flash Joule Heating was developed at Rice University and heats materials to over 3,000°C in milliseconds, which is hotter than the surface of the sun. Flash Metals USA plans to productise this technique starting in Q1 2026.

- Thermal-electrical methods (for example, Flash Joule Heating): These newer techniques subject powdered scrap to very rapid, high-temperature pulses or to controlled electrical heating. The goal is to vapourise or oxidise base metals and organics quickly, while leaving REE oxides behind as a solid concentrate. These routes can greatly reduce liquid chemical use and lower emissions. They also promise faster cycle times and simpler waste streams. Limitations today include the need to preprocess feedstock into a highly granular, powdered form. Moreover, being a new method, there are still questions about its scale-up potential, owing to the higher capital cost of specialised equipment required for this technique.19

Meanwhile, no matter which pathway is chosen, the usual product leaving these plants is a rare-earth oxide or salt. The resultant intermediate must be then reduced, alloyed and refined into metals and usable alloys before it can be fed into magnet-making or other manufacturing.

Source: Authors Creation

Source: Authors Creation

Why Urban Mining?

The Strategic and Economic Case

The strategic and economic case for Indian urban mining is compelling.

Resource security is the most obvious benefit. Recycling offers the most direct path to mitigating India’s extreme import dependence, thus creating a sovereign supply chain from a fully indigenous resource. This would insulate domestic industries from geopolitical disruptions and price weaponisation.

Beyond just supply-chain security, there is also the richness of the ore. The high-grade, high-density feedstock—like magnets—makes recycling inherently more efficient, bypassing the need to directly mine and process tonnes of rock. An efficient process could thus offer significantly lower energy, chemical, and capital costs per kilo of output.20

This, in turn, builds economic value and a circular economy. When e-waste is shredded or dumped, valuable materials like Neodymium and Dysprosium are permanently lost.21 Recycling captures this value and spawns an entirely new high-tech industry. Here, India’s large, technically-skilled workforce and established expertise in chemical engineering could lend a significant comparative advantage. The country has the potential to develop a competitive edge in recycling technology and services. This opens up the possibility for India to become a global hub for processing REEs from waste.

India holds roughly 25% of the world’s Thorium reserves. This was once seen as a strategic asset for nuclear energy under India’s three-stage nucelar programme, but has since become a regulatory burden for REE mining. Every tonne of thorium stockpiled is an additional regulated radioactive liability requiring monitored and conditioned storage.

India faces an additional specific problem with direct mining: co-location with Thorium. The country’s primary REE reserves are in monazite sands, which are co-located with Thorium.22 Although the Thorium in these sands is not radioactive enough to block mining outright, it still brings the deposits under the jurisdiction of the Department of Atomic Energy.23 This makes the regulatory landscape significantly lengthier and more heavily scrutinised. It is a key reason why India has seen very little private participation in REE mining, and why the only major operator remains a government-run entity.

Recently, the government has begun opening the door for private involvement in non-atomic critical minerals as part of the National Critical Mineral Mission.24 However, this relaxation does not extend to monazite-bearing sands, which is still where a vast majority of India’s REEs are located. Rules introduced in 2025 keep atomic minerals under tight state control or centre-nominated agencies, which means Thorium-bearing deposits continue to face additional scrutiny and remain effectively closed to private mining.25

Environmental Case

The tailings from REE processing often contain radioactive Thorium and Uranium. China’s Baogang tailings pond in Inner Mongolia is one of the world’s largest toxic lakes.

The strategic and economic arguments are further reinforced by environmental benefits. Primary REE mining is ecologically destructive. Low-grade ores require vast open-pit mines, and the refining process uses various toxic chemicals. Estimates suggest that producing one tonne of REE oxide generates up to 2,000 tonnes of toxic waste, also referred to as tailings.26

Recycling offers a cleaner alternative. It avoids new ecological disturbance from mining and, just as importantly, directly addresses India’s existing e-waste crisis. The country generates 1.7 to 2.0 million tonnes of e-waste annually27—much of it handled by an informal sector using hazardous methods, like open-wire burning and crude acid leaching.28 These practices release a torrent of lead, mercury and other toxins.

Formal, regulated recycling turns this liability into an asset. It creates an economic incentive to channel waste away from polluting informal methods into controlled facilities. Even conventional Hydrometallurgy, when regulated, captures and treats its hazardous outputs. Newer technologies like Flash Joule Heating promise even greater gains, with studies showing 84% reductions in emissions and 90% in energy use, while avoiding liquid acid waste. Recycling is thus a double win: it prevents future harm from mining, while mitigating the present-day harm from e-waste mismanagement.

India’s Unique Potential

As the world’s third-largest e-waste generator, India’s cities are sitting on a vast and growing repository of critical minerals. As stated previously, India imported over 53,000 tonnes of NdFeB magnets in FY 2024-25. This translates to a total national demand baseline of approximately 17,000 tonnes of Rare Earth Oxide (REO) equivalent per year. This is owing to the fact that roughly 30% of magnets are rare-earth by mass, with the rest being other metals like Iron and Boron.

Against this 17,000-tonne demand, we can model the potential supply from India’s e-waste.

Current Potential (c. 2025)

The current base-load of recoverable REEs comes from products discarded today.

The voice coil motor in an HDD, which moves the read/write head, contains some of the highest-grade NdFeB magnets. Japan’s Hitachi already recovers 97% of magnets from end-of-life HDDs on semi-automated lines.

- IT Equipment (HDDs): This is the most significant current source. India generates around 100,000 tonnes of discarded Hard Disk Drives (HDDs) per year. This stream, containing 3,000-4,000 tonnes of magnet material, could yield approximately 1,200 tonnes of recoverable REO annually (check Appendix A for the derivation). This source is critical, but it is also temporary, as the market shifts from HDDs to Solid-State Drives (SSDs), which contain no rare-earth magnets.29

The REE content in a smartphone is worth less than ₹5. The gold, however, is worth nearly ₹200, which is why informal recyclers focus on precious metals and ignore rare earths entirely.

Smartphones: While the volume of discarded smartphones is enormous (an estimated 267 million units/year), the REE content per unit is trivial. Each phone contains only 0.082 grams of REEs in its magnets (for haptics and speakers). This entire stream yields only ~25 tonnes of REO (check Appendix A for the derivation). The economic driver for phone recycling remains gold and copper, not rare earths.

Consumer Appliances: This stream is also negligible today. The appliances being junked in 2025 were purchased 10-15 years ago, largely before the adoption of permanent-magnet motors. This stream is estimated to yield only ~25 tonnes of REO.

Today’s total potential supply is approximately 1,250-1,300 tonnes of REO, which could theoretically satisfy 7.6% of India’s annual demand.

Future Potential (c. 2030-2040)

However, investing in recycling is still crucial as volumes are set to increase substantially in the coming decade, and setting the infrastructure right early is key to capturing this value. Truly massive volumes will come in from the maturing waste streams of India’s green transition.

Electric Vehicles (EVs): This stream will become a major generator, replacing HDDs.

- Four-Wheelers (Cars): An estimated 1.915 million scrapped units, each with ~1.5 kg of magnets, will yield ~2,000 tonnes of REO (check Appendix A for the derivation).

- Two-Wheelers (Scooters): The volume of this segment (15.32 million units) makes it equally significant, with ~80-150 grams of magnets per unit, making the stream yield around ~1,225 tonnes (check Appendix A for the derivation).

- This entire EV stream is therefore projected to generate ~3,200 tonnes of REO annually.

Wind Turbines: Based on India’s installation targets30 and a 20-25 year lifespan31, the turbines decommissioned around 2035 will be a major resource. Assuming 25% of new installations are magnet-heavy PMSG turbines (using 3.0 tonnes of magnets per MW), this stream will generate ~2,020 tonnes of REO annually.

Consumer Appliances: As the inverter ACs and BLDC-motor washing machines sold today reach end-of-life, this stream will mature, yielding an estimated ~660 tonnes of REO annually.

Source: Authors Creation

Source: Authors Creation

As Table 1 illustrates, while today’s potential (6.4%) is certainly useful, it is dependent on the declining HDD stream. The future potential (35.5%) is significant, but if the recycling ecosystem is not developed properly in India, then this resource will be lost. Building the recycling capacity now is essential to ensure India is prepared to capture this massive future feedstock, as and when it becomes available. If the required infrastructure is properly developed in India, then this figure could be even higher, as feedstock can be imported and recycled domestically.

The Current Landscape

Impediments to Urban Mining

Despite India’s clear potential for urban mining, a formal rare-earth recycling industry is non-existent. This gap is the outcome of interconnected barriers in market structure, economic viability, and flawed public policy. Understanding these impediments is the first step toward effective interventions.32

Dominance of the Informal Sector

India’s informal recycling sector employs an estimated 1.5 million people.

The most immediate impediment to come up for recycling firms is in securing feedstock. This is because any formal recycling firm would have to compete with a deeply entrenched informal recycling sector. An estimated 85-90 percent of all electronic waste in India is collected and processed by the informal sector.33 This network of small-scale scrap dealers (kabadiwalas) and rudimentary dismantlers operates on a simple, powerful model: providing convenience and immediate cash to consumers and businesses for their discarded goods.

This sector, however, operates on a logic of “cherry-picking.” Informal players use low-cost, low-tech, and often hazardous methods to extract only the materials that are easiest to access and have an immediate, high value in established local scrap markets. These methods include stripping cables for copper, manually breaking circuit boards, and using open-air burning or crude acid baths to recover gold, silver, and tin.34

In this economic ecosystem, rare-earth elements are effectively invisible. The informal sector has neither the incentive nor the capability to recover them.

Lack of Incentive: A kabadiwala dismantling a computer Hard Disk Drive (HDD) is paid for the aluminium platter and the steel casing. The small, powerful NdFeB magnets inside—the most strategically valuable component—have no established scrap value. They are treated as contaminants and are typically left attached to the steel or aluminium scrap.35

Lack of Capability: Even if an incentive existed, the informal sector lacks the technology to conduct the processes required to extract REEs. This extraction is not a physical process, but a complex chemical one.

However, the consequence of this dominance by the informal sector is twofold. First, it distributes and destroys the feedstock. The informal network acts as a giant sieve and ultimately reduces the feedstock available to the formal supply chain. It efficiently pulls thousands of tonnes of e-waste out of the system, strips it of easy-to-recover value, and in the process, contaminates, damages, or discards the REE-bearing components.36

Second, the informal sector shapes the economics of e-waste collection in ways that formal recyclers must take into account. Kabadiwala networks offer convenience, doorstep service and immediate cash, which makes them the first point of contact for most discarded electronics. As they operate with very low overheads, they can afford to pay slightly more for raw scrap at the source than a formal recycler who must meet licensing, pollution-control and safety requirements. This makes it harder for formal enterprises to secure steady volumes of REE-bearing components. A more constructive path is to integrate these informal collectors into the emerging urban-mining chain through buy-back partnerships or aggregator models, so that they remain key stakeholders rather than competitors.37

Economic and Technical Viability

Even if the feedstock challenge from the informal sector were solved, a potential plant faces further hurdles in terms of economic and technical barriers that make REE recycling a difficult-to-bank proposition.38

Prohibitive Capital Cost (CAPEX): Extracting rare earths is not a simple manufacturing process; it is a tech and capital-intensive industrial one, akin to building a small-scale mineral refinery. A full-scale hydrometallurgical plant to process magnet scrap requires specialised machinery like corrosion-resistant chemical reactors, solvent extraction circuits, precipitation tanks, and calcination furnaces. The capital cost for a commercially viable plant, depending on its scale, is estimated to be in the hundreds to thousands of crores of rupees. This creates a formidable barrier to entry for all but the largest and most risk-tolerant corporations.39

Price Volatility: This is perhaps the single greatest deterrent to private investment. The global rare-earth market is not a stable, transparent commodity market like gold. It is notoriously volatile and opaque, with prices subject to the production quotas and strategic decisions of its dominant player, China. The market saw prices spike by 500-1,000 percent in 2011 after China restricted exports, only to crash in the following years. This volatility makes rational business planning impossible. Investors are wary of China’s potential to use predatory pricing, flooding the market with cheap, subsidised oxides, to bankrupt any nascent international competitor as soon as it becomes a threat.40

Domestic Demand: A new REE recycler in India faces a critical market void. As of today, there are few large-scale domestic buyers for separated rare-earth oxides. The primary customers—manufacturers of permanent magnets—do not exist at scale in India. This creates a classic coordination failure: recyclers are hesitant to invest hundreds of crores without a guaranteed domestic customer, while potential magnet manufacturers are hesitant to build their plants without a guaranteed domestic supply of raw materials. This forces any potential recycler to compete in the volatile global export market, where they must again compete with Chinese firms and their state-supported prices. The new ₹7,280 crore scheme to build domestic rare-earth permanent magnet capacity helps address this gap. By supporting up to 6,000 tonnes of annual magnet production through sales-linked incentives and capital support, it creates a predictable domestic market that did not previously exist. If the programme also allows, or even encourages, the use of recycled feedstock, this new demand can become a stable offtake route for recycled rare earths. This, in turn, will offer future recyclers clearer visibility on buyers and improve the bankability of their projects.41

High Opportunity Cost: Even established, formal e-waste recyclers in India have rationally chosen to ignore rare earths. Their business models are built on the immediate and proven returns from recovering gold, silver, copper, and aluminium from printed circuit boards, or lithium and cobalt from batteries. The return on investment (ROI) for these materials is high, the technology is understood, and the markets are liquid. In contrast, the ROI for rare earths is distant, uncertain, and technically complex. Given finite capital, companies will always allocate it to the most profitable and least risky venture. REE recycling is, by a wide margin, the least profitable and most risky.

Distributed Feedstock: Unlike a primary mine—which is a single, concentrated geological deposit—an “urban mine” is a diffused and chaotic resource. The feedstock is distributed across millions of households and businesses in countless different products. Aggregating a consistent, high-volume supply of specific REE-rich components is a logistical nightmare. The risk of an inconsistent supply is a big one, and could potentially leave a billion-dollar plant idle.42

Technical and Operational Hurdles: Finally, the technical challenges are non-trivial. The process is not one-size-fits-all; recycling magnets from small HDDs require a different material-handling and chemical process than recycling large, coated magnets from EV motors. Furthermore, a lack of domestic R&D and technical standards in the field means that companies must either innovate in a domestic vacuum, or pay for expensive technology licenses from foreign firms, adding yet another layer of cost and risk.43

Policy Impediments

This market failure within India’s domestic recycling market has not been corrected by public policy. In fact, many e-waste recycling policies disincentivise rare-earth recycling.

1. The E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022

India’s E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022, are built on an Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework.44 On paper, this system is supposed to channel waste to formal recyclers through a digital credit mechanism. Producers of electronic equipment must meet annual recycling targets, expressed as a percentage of the quantity of products they placed on the market in previous years. These obligations are quantified in tonnes of e-waste, and fulfilled by purchasing EPR certificates generated by authorised recyclers on the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) portal.

Initially, this regime relied almost entirely on weight-based metrics, rewarding recyclers purely by the tonnage of waste processed. That design risked ignoring the value of individual materials and favouring low-cost, bulk processing. Recognising this, the CPCB issued a 2023 Framework that redefined the process of certificate generation.45

Under the revised system, certificates are issued not for generic weight, but for the recovery of specified key metals: gold, copper, aluminium, and iron (including steel)—each assigned a standard composition factor for different categories of electronic products. Only these metals currently generate tradable credits. The framework also states that rare earths and other precious materials will be “considered and incentivised” in future iterations, though no operational formula exists yet.

In practice, this architecture still creates uneven incentives. Because recyclers earn certificates only for recovering the four listed metals, they have little economic motivation to invest in the complex processes needed to extract rare-earth elements (REEs) or other non-listed critical minerals. These materials—though strategically vital—are low in mass and costly to separate, yielding no direct EPR revenue. As a result, the framework’s current scope remains narrow, implicitly favouring high-volume metal recovery over high-value mineral recovery.

2. Institutional Silos

Responsibility for the REE supply chain is currently fragmented across a half-dozen government bodies, namely the Ministry of Mines, the Department of Atomic Energy (due to monazite), the Ministry of Environment (for e-waste), and the Ministry of Heavy Industries (for end-use in EVs). This policy siloing has prevented the formation of a single, coherent national strategy.46

3. Insufficient Financial Support

The government’s new incentive scheme for critical mineral recycling—announced in 2025—is a welcome acknowledgement of the problem, but is financially insufficient to solve it. The scheme’s total outlay is modest at ₹1,500 crore, but its critical flaw is the cap of ₹50 crore per entity.47

Against the backdrop of a ₹1,000+ crore (depending on scale) capital cost for a single viable plant, this ₹50 crore incentive is little more than a token gesture. It is an insignificant amount that cannot de-risk an investment of this magnitude. It may help a small-scale pilot project, but it is not a serious industrial policy tool capable of building a new, capital-intensive domestic industry.

4. Import Restrictions

To prevent India from becoming a dumping ground for global e-waste, the government has banned the import of most e-waste scrap. This was done under the Hazardous and Other Wastes Rules, with environmental protection in mind.48 However, such a rigid, blanket ban starves nascent domestic recyclers of a potential source of consistent, high-volume feedstock from abroad. Moreover, India’s own feedstock (4,000 tonnes) is not nearly enough to meet our permanent magnet demand (53,000 tonnes). Therefore, it is essential that we import feedstock from other countries to recycle here.

Recommendations

Building a domestic rare-earth recycling industry in India, given the significant impediments, requires policy change. These recommendations are designed to work in concert to de-risk private investment, create a viable market, and secure the necessary feedstock.

Creating Market Demand

The most significant and immediate policy barrier is the perverse incentive structure of the current E-Waste (Management) Rules. The system’s design actively discourages, or at best ignores, rare-earth recovery. While the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework correctly creates a market for recycling certificates, it fails to differentiate by strategic value. Its current categories for generating certificates simply do not yet operationalise rare-earth elements. This omission creates a zero-incentive environment. A formal recycler has no market-based reason to invest in the complex, high-cost processes for REE extraction when they receive no regulatory or financial credit for doing so.

The primary recommendation is to immediately amend the E-Waste Rules to include REE-bearing components as a distinct, high-value category for generating EPR certificates. This must be implemented through a strategic multiplier system. Under this model, recycling one kilogram of a designated critical material (like NdFeB magnet scrap) would generate significantly more EPR credits than recycling one kilogram of a bulk material (like steel). This multiplier would, for the first time, make the strategic value of these materials tangible to the market.49

This single change would create a powerful market pull. Producers of electronics, needing to meet their EPR obligations, would be incentivised to procure these new, high-value REE certificates. This creates a new, guaranteed, and premium revenue stream for formal recyclers. Armed with this bankable revenue, formal recyclers can subsequently pay a higher price for the REE-bearing feedstock (like discarded hard disk drives). This allows them to “outbid” the informal sector at the source, channeling this critical waste stream into the formal system. This is a market-based solution that solves the feedstock problem without requiring direct, and often ineffective, state intervention into the informal economy.

The EPR reform, on its own, is necessary but insufficient. It creates a market for the feedstock but does not solve the investment problem. No rational private entity, or financial institution, will underwrite a large loan for a recycling plant when its primary revenue source (REE oxides) is subject to extreme price volatility.50

To overcome this, the government must provide a mechanism to ensure bankability for first-movers. A time-bound price floor, or an assured offtake program, for domestically recycled rare-earth oxides is essential.

One effective model would be a procurement guarantee managed by a designated agency. This agency would commit to purchasing a fixed, escalating tonnage of specific rare-earth oxides (e.g., Neodymium oxide, Dysprosium oxide) from domestic recyclers at a predetermined support price, perhaps set via a competitive reverse auction to ensure efficiency. This guarantee would act as an insurance policy for recyclers. It ensures that if global prices crash or if domestic buyers are not yet at scale, their output will not go unsold.

The procured material would not be a dead-weight loss; it could form the basis of a National Critical Mineral Stockpile, a key strategic buffer. This intervention is not a permanent subsidy but a temporary bridge, designed to help the nascent industry achieve economies of scale, after which it can compete on its own.

Institutional and Financial Support

The procurement guarantee de-risks the revenue side of rare-earth recycling. The next barrier is upfront capital risk. Recycling plants are capital-intensive, chemically complex, and exposed to volatile global prices. Without public participation, it is highly risky, and therefore unlikely for private capital to enter at scale.

KABIL has signed agreements for lithium in Argentina and cobalt in the DRC, but rare earths remain absent from its portfolio. Its mandate is exclusively outward-facing, acquiring equity in overseas assets. India needs an inward-facing counterpart to de-risk domestic recycling.

KABIL has proven to be an effective state instrument, but its mandate is exclusively outward-facing. It acquires equity in overseas mining assets to diversify supply.51 This leaves a critical domestic gap. There is no equivalent state-backed institution empowered to de-risk and co-invest in high-capital projects, such as domestic recycling and refining facilities.

India therefore needs an inward-facing counterpart. This can be structured either as a new vertical within KABIL, or as a dedicated vehicle under the National Critical Mineral Mission. For clarity, this paper refers to it as IN-KABIL.

The purpose of IN-KABIL should not be to provide grants, but to function as a strategic co-investor. Its core mandate should be to make capital deployment possible where markets fail. This includes taking minority equity stakes in early projects, providing first-loss guarantees on debt, and most importantly, anchoring long-term offtake guarantees.

Offtake guarantees are essential. No recycling plant can raise large-scale financing if its primary output is exposed to extreme price volatility. IN-KABIL should commit to purchasing a fixed quantity of specified rare-earth oxides from approved domestic recyclers at a predefined floor price for a limited period, such as five to seven years. The price needs to cover operating costs and debt servicing. It is not a permanent subsidy, but a temporary bridge to scale.

These guarantees change how projects are assessed. Instead of relying on uncertain spot prices, recyclers can plan around predictable sales. This improves cash-flow visibility, and makes long-term borrowing feasible. The material purchased under these arrangements does not have to be stockpiled without purpose. It can be held as part of a national critical mineral reserve, or channelled to domestic magnet producers through clearly defined allocation mechanisms. In this way, public risk-taking is converted into tangible strategic assets rather than open-ended fiscal support.

This approach has precedent. Japan’s public institutions actively de-risk domestic critical mineral projects to crowd-in private capital.52 The same logic applies here. Without an institution like IN-KABIL, rare-earth recycling will remain stuck in a coordination failure, regardless of technical feasibility or strategic urgency.

Beyond new institutional mechanisms, existing policies must be corrected. The ₹1,500 crore critical mineral recycling scheme is mis-scaled. Its ₹50 crore cap per entity is insignificant against the capital cost of a viable plant, which can run into thousands of crores. In its current form, the scheme cannot materially de-risk investment. These funds would be better deployed through the IN-KABIL co-investment and offtake framework.

The ₹7,280 crore scheme to build domestic rare-earth permanent magnet capacity is a positive step. It aims to support 6,000 tonnes per year of integrated magnet manufacturing. However, the scheme does not yet specify eligible feedstocks. If recycled rare earths are excluded or treated ambiguously, new magnet plants may remain dependent on imported oxides. The scheme should therefore be explicitly source-agnostic and aligned with the recycling incentive framework, so that recycled domestic material becomes a recognised and bankable input.

Without this alignment, India risks building downstream capacity while leaving the upstream recycling opportunity unrealised.

Securing the supply chain

Finally, a mature recycling industry needs a scaled, consistent feedstock. India’s domestic e-waste stream (yielding an estimated ~4,000 tonnes of REE) is a critical starting point. However, it is a fraction of India’s import-driven demand (represented by 53,000 tonnes of magnets). A domestic recycling industry, once built, will be feedstock-starved if it relies on domestic waste alone.

Yet, the current blanket ban on e-waste imports—part of the Hazardous and Other Wastes Rules—makes this impossible. While environmentally well-intentioned (to prevent India from becoming a “dumping ground”), this rigid ban is now a strategic roadblock.

This policy must be reformed. India should create a “green channel” for selective, licensed import of specific, high-value, processed scrap (e.g., sorted magnet scrap, battery black mass). This channel would only be accessible to authorised, high-tech domestic recyclers who adhere to strict environmental standards. This will allow India to leverage its potential recycling expertise as a global service.

These three recommendations offer a roadmap for making urban mining viable in India.

Appendix A: Estimation for Urban Mining Potential

The estimate of ~100,000 tonnes of discarded HDDs per year is derived by triangulating official and industry-wide assessments of India’s e-waste volumes. Official monitors place annual e-waste generation at 1.7–2.0 million tonnes53, whereas industry reports—which apply a broader definition of e-waste and capture informal-sector flows—suggest a higher figure of around 3.8 million tonnes.54 Multiple studies indicate that computer equipment forms the largest share of India’s e-waste stream. Using a working assumption that computer devices make up roughly 50–60 percent of total e-waste55, and that HDDs account for 4–5 percent of the mass of an average desktop or laptop56 (based on the typical weights of 3.5” and 2.5” drives relative to full system mass), produces an implied HDD waste stream in the range of 70,000–120,000 tonnes per year.

To convert HDD mass into REO potential, the estimation uses the typical NdFeB magnet content per HDD, which is approximately 2–4 percent of drive mass.57 Applying this to 100,000 tonnes of HDDs gives 3,000–4,000 tonnes of magnet material. NdFeB magnets contain roughly 30% rare-earth metal, and converting metal to oxide uses a standard 1.17× factor.58 Using these accepted ratios yields approximately 1,200 tonnes of recoverable REO, which matches the number used in Section 3.

The smartphone calculation begins with an estimated 267 million discarded units per year, derived from India’s ~800 million smartphone users and an average 3-year replacement cycle.59 Each phone contains roughly 0.08 grams of REE in its small magnets (in speakers, haptics, autofocus units).60 Multiplying 267 million units by 0.08 grams yields ~21 tonnes of REE metal, which converts to ~25 tonnes of REO using the 1.17 factor.

The estimate for current appliance-based REE recovery reflects that most end-of-life appliances in 2025 were produced before inverter BLDC motors became widespread. For this reason, only a small fraction of today’s appliance stream contains NdFeB magnets. Using a working assumption of 1 million BLDC-equipped appliances reaching end-of-life per year61, each containing roughly 75 grams of NdFeB material62, yields ~75 tonnes of magnets, which converts to ~26 tonnes of REO.

The EV end-of-life projection uses India’s 2030 EV sales targets as a proxy for 2040 scrappage volumes. Projected sales include 1.915 million four-wheelers, 15.32 million two-wheelers, and 1.6 million three-wheelers.63 Typical magnet content assumptions are 1.5 kg per four-wheeler, 150 g per two-wheeler, and 300 g per three-wheeler.64 Multiplying these yields ~5,744 tonnes of NdFeB magnets entering the waste stream annually. Applying the standard 30% REE and 1.17 oxide conversion factors yields approximately 2,000 tonnes of REO.

The wind-turbine estimate is based on India’s installation trajectory toward 2030 and a 20-25 years operating life.65 Approximately 8.8 GW of wind capacity is being added annually; assuming 25% of turbines use permanent-magnet synchronous generators (PMSGs), and using an average magnet loading of 3 tonnes per MW66 (from modern offshore and high-efficiency PMSG specifications), produces an expected end-of-life magnet volume of ~6,600 tonnes per year. Converting this via the 30% REE and 1.17 oxide factors yields ~2,300 tonnes of REO.

Appendix B: Proposal for Pilot Study

One of the most difficult challenges, as discussed in this paper, for urban mining is securing high-quality feedstock before it is dissipated into the informal recycling ecosystem. This problem is best addressed through controlled pilot programmes that demonstrate how concentrated e-waste streams can be funnelled to formal recycling projects at source.

A practical pilot could be built around a large Indian industrial group with diverse operations and high internal e-waste generation. Such a group would produce REE-rich waste across multiple business verticals like IT hardware, electric motors, industrial electronics, etc. By aggregating this waste internally and routing it directly to a formal recycler, the group can bypass the informal sector entirely.

For example, a large IT services arm generates a steady stream of end-of-life hard disk drives and servers. An automotive arm generates permanent-magnet motors and power electronics. Under a pilot framework, these waste streams would be collected, sorted, and pre-processed to preserve magnet integrity. The material would then be supplied to a domestic recycling facility under a long-term contract.

This arrangement creates three benefits. First, it provides a guaranteed, high-concentration feedstock stream for the recycler, improving plant utilisation and economics. Second, it demonstrates to other large firms that internal aggregation is feasible and even economically beneficial without regulatory friction. Third, it allows people driving policy to observe and learn from real material flows, costs, and bottlenecks before scaling the model nationally.

Such a pilot could also be linked to the proposed IN-KABIL framework. The same corporate group could act as a partial offtake partner for recycled output, closing the loop within a single ecosystem. The demonstration effect of a successful pilot would be significant, especially if implemented by a highly visible industrial group.

Pilots of this nature are not meant to solve the problem at scale. Their purpose is to validate institutional design, test coordination mechanisms, and reduce uncertainty. Success in the pilot will provide confidence to deploy capital at scale.

Footnotes

International Energy Agency. 2025. “Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025.” Link↩︎

Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China. 2025. “Announcement No.18 of 2025.” Link↩︎

Based on an interview with an industry leader in India.↩︎

Anirudh Kanisetti, Aditya Pareek, and Narayan Ramachandran. 2020. “A Rare Earths Strategy for India.” The Takshashila Institution. Link↩︎

Gschneidner, Karl A. 2025. “Rare-earth element | Uses, Properties, & Facts.” Britannica. Link↩︎

The Northern Miner. 2021. “GMS: Rare earth elements market under the spotlight.” November 19, 2021. Link↩︎

Dushyantha et al. 2020. “The story of rare earth elements (REEs): Occurrences, global distribution, genesis, geology, mineralogy and global production.” Ore Geology Reviews 122 (103521). Link↩︎

United States Department of Energy. 2020. “Critical Minerals Strategy.” Department of Energy. Link↩︎

Papagianni et al. 2022. “Preprocessing and Leaching Methods for Extraction of REE from Permanent Magnets: A Scoping Review.” AppliedChem 2, no. 4 (October): 199-212. Link↩︎

United States Geological Survey. 2025. “Mineral Commodity Summaries - Rare Earths.” Link↩︎

Indian Bureau of Mines. 2023. “Indian Minerals Yearbook.” Link↩︎

“India ranks 3rd in rare earth reserves, but trails in production due to structural bottlenecks in mining: Report.” 2025. The Economic Times. Link↩︎

Ministry of Heavy Industries. 2025. “Disruption in the supply of Rare Earth Magnets.” Press Information Bureau. Link↩︎

Xavier, Lúcia H., Marianna Ottoni, and Leonardo Picanço Peixoto P. Abreu. 2023. “A comprehensive review of urban mining and the value recovery from e-waste materials.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 190, no. 106840 (March). Link↩︎

Heim, Markus, et al. 2023. “An Approach for the Disassembly of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Rotors to Recover Rare Earth Materials.” Procedia CIRP 116:71-76. Link↩︎

Rabeea, Muwafaq A, et al. 2025. “Dissolution of rare-earth elements (Nd, Dy and Pr) in end-of-life neodymium magnet by an ultrasound-assisted electrochemical process.” Electrochimica Acta 543, no. 147579 (December). Link↩︎

Pereira, Bárbara D, et al. 2026. “Hydrometallurgical innovations for recovery of rare earth elements from secondary sources: A comparative review.” Journal of Rare Earths 44, no. 1 (January): 1-14. Link↩︎

Kaya, Muammer. 2024. “An overview of NdFeB magnets recycling technologies.” Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 46, no. 100884 (April). Link↩︎

Luna, Marcy D. 2025. “Rapid flash Joule heating technique unlocks efficient rare earth element recovery from electronic waste.” Rice University. Link↩︎

Baskaran, Gracelin, and Meredith Schwartz. 2025. “Developing Rare Earth Processing Hubs: An Analytical Approach.” CSIS. Link↩︎

“Why Rare Earth Recovery from E-Waste Matters for India.” 2025. Attero Recycling. Link↩︎

Jacob, Jacob B. 2025. “India’s Thorium Reserves: Nuclear Potential & Challenges.” The secretariat. Link↩︎

“Press Release 10/2012.” 2012. Department Of Atomic Energy. Link↩︎

“National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM).” 2025. Ministry of Mines. Link↩︎

Department of Atomic Energy. 2025. “Offshore Areas Atomic Mineral Operating Right Rules, 2025.” Ministry of Mines. Link↩︎

Nayar, Jaya. 2021. “Not So”Green” Technology: The Complicated Legacy of Rare Earth Mining.” Harvard International Review. Link↩︎

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. 2023. “Generation of E-waste.” Press Information Bureau. Link↩︎

Kumari, Hina, and Sudesh Yadav. 2023. “A comparative study on metal pollution from surface dust of informal and formal e-waste recycling sectors in national capital region of New Delhi and associated risk assessment.” Science of The Total Environment 904, no. 166791 (December). Link↩︎

Nkiawete, Mpila M., and Randy L. Wal. 2025. “Rare earth elements: Sector allocations and supply chain considerations.” Journal of Rare Earths 43, no. 1 (January). Link↩︎

Global Wind Energy Council. 2025. “India’s wind capacity expected to reach 107 GW by 2030: GWEC India Wind Report 2025.” Global Wind Energy Council. Link↩︎

“Can wind turbine blades be recycled?” 2023. National Grid. Link↩︎

Goldar, Amrita, et al. 2025. “Unravelling India’s E-waste supply chain: A comprehensive analysis and mapping of the key actors involved.” Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER). Link↩︎

United Nations Development Programme. 2025. “India advances transition to a circular economy in the electronics sector with GEF and UNDP support.” Link↩︎

Annamalai, Jayapradha. 2015. “Occupational health hazards related to informal recycling of E-waste in India: An overview.” Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 19 (1): 61-65. Link↩︎

Lines, Kate, and Ben Garside. 2026. “Clean and inclusive? Recycling e-waste in China and India.” International Institute for Environment and Development. Link↩︎

Reinsch, William A. 2021. “A Canary in an Urban Mine: Environmental and Economic Impacts of Urban Mining.” Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Link↩︎

International Institute for Environment and Development. 2014. “Innovations for inclusivity in India’s informal e-waste markets.” Link↩︎

Rizas, Vasileios, Edoardo Righetti, and Amin Kassab. 2024. “Understanding the barriers to recycling critical raw materials for the energy transition: The case of rare earth permanent magnets.” Energy Reports 12 (December): 1673-1682. Link↩︎

Nili, Sheidi. 2025. “Reclaiming Value from Waste: A Techno-Economic Evaluation of Rare Earth Extraction from Coal Refuse.” ACS Sustainable Resource Management 2, no. 9 (September). Link↩︎

Mancheri, Nabeel A, et al. 2019. “Effect of Chinese policies on rare earth supply chain resilience.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling 142 (March): 101-112. Link↩︎

Press Information Bureau. 2025. “Cabinet Approves Rs.7,280 Crore Scheme to Promote Manufacturing of Sintered Rare Earth Permanent Magnets (REPM).” Link↩︎

Zhang, Shuxin, and Yun Shen. 2025. “Urban Biomining of Rare Earth Elements: Current Status and Future Opportunities.” ACS Environmental Au, (November). Link↩︎

Perry, Anna, and Kelsi V. Veen. 2024. “Recovering Rare Earth Elements from E-Waste: Potential Impacts on NdFeB Magnet Supply Chains and the Environment.” United States International Trade Commission. Link↩︎

Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change. 2025. “E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022.” Central Pollution Control Board. Link↩︎

Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change. 2023. “Framework for generation of EPR Certificate under E-Waste (Management) Rules, 2022.” Central Pollution Control Board. Link↩︎

Ministry of Mines. 2023. “For India Critical Minerals.” Link↩︎

“Cabinet approves Rs.1,500 crore Incentive Scheme to promote Critical Mineral Recycling in the country.” 2025. Press Information Bureau. Link↩︎

Central Pollution Control Board. 2016. “Hazardous and other Wastes (Management & Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016.” Link↩︎

Sustainable Packaging Coalition. 2025. “Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Eco-modulation Overview.” Link↩︎

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. 2023. “China’s rare earths dominance and policy responses.” Link↩︎

“Khanij Bidesh India Ltd.” n.d. KABIL India - Joint Venture for Critical Minerals. Link↩︎

Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security. n.d. “JOGMEC.” Link↩︎

Chatterjee, Sandip. 2024. “Electronic Waste and India.” Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology. Link↩︎

Attero Energy. 2025. “Challenges Faced by Indian Businesses in E-Waste Disposal.” Link↩︎

Dey, Subhashish, et al. 2023. “Recycling of e-waste materials for controlling the environmental and human heath degradation in India.” Green Analytical Chemistry 7, no. 100085 (December). Link↩︎

Skrzekut, Tomasz, Maciej Wędrychowicz, and Andrzej Piotrowicz. 2023. “Recycling of Hard Disk Drive Platters via Plastic Consolidation.” Materials (Basel) 16, no. 20 (October). Link↩︎

München, Daniel D., and Hugo M. Veit. 2017. “Neodymium as the main feature of permanent magnets from hard disk drives (HDDs).” Waste Management 61 (March): 372-376. Link↩︎

Goonan, Thomas G. 2011. “Rare Earth Elements—End Use and Recyclability.” United States Geological Survey. Link↩︎

The Hindu Bureau. 2024. “Smartphone replacement cycle in India increased from 24 months to almost 36 months.” Business Line. Link↩︎

Stein, Ronei T., Angela C. Kasper, and Hugo M. Veit. 2022. “Recovery of Rare Earth Elements Present in Mobile Phone Magnets with the Use of Organic Acids.” Minerals 12 (6). Link↩︎

Abhyankar, Nikit, et al. 2017. “Assessing the Cost-Effective Energy Saving Potential from Top-10 Appliances in India.” Link↩︎

Prosperi, D, et al 2018. “Performance Comparison of Motors Fitted with Magnet-To-Magnet Recycled or Conventionally Manufactured Sintered NdFeB.” Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 460 (August): 448–53. Link↩︎

Bhatiani, Gaurav, Sahil Chandra, and Aastha Jain. 2024. “EV Aggregates Value Chain in India.” RTI International. Link↩︎

Heim, James W., and Randy L. Wal. 2023. “NdFeB Permanent Magnet Uses.” Scholarly Community Encyclopedia. Link↩︎

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2013. “Renewable Energy Fact Sheet: Wind Turbines.” Link↩︎

United States Department of Energy. 2024. “Rare Earth Permanent Magnets.” Link↩︎