Juggernaut or Embers of a Dying Fire: China’s Technology Landscape and Its Implications for India

Draft of a chapter published in the book “China: Indian Perspectives” by the Hindu Group. Buy the book here

Authors

Abstract

China has rapidly emerged as a technological powerhouse, capturing global attention with new advancements and breakthroughs across multiple technology areas. This chapter examines the ingredients key to China’s remarkable technological rise. Specifically, it goes beyond simplistic explanations like state capitalism and intellectual property (IP) theft, and argues that China’s success is due to the combination of several fundamental factors and specific government policies. These fundamental factors include a supportive external environment and international linkages, massive capital inflows and foreign technology transfers, state focus, a capable workforce, and a demanding consumer base.

Further, the chapter analyses changes in China’s technology ecosystem since Xi Jinping assumed power. It zooms in on Xi’s intensified state control, new policy instruments, and aggressive posturing. All of these have, in turn, changed the world’s response to China, tipping the geopolitical environment from one that China could leverage to advance its interests to one that is increasingly hostile and distrustful toward it.

The chapter studies these shifts alongside other structural weaknesses and emerging challenges within the Chinese technology system and offers insights into the ecosystem’s potential future trajectory. It concludes with recommendations for India to counter China’s bustling activity in the technology arena. It makes the case for a calibrated strategy to deal with China’s technology exports, investments and talent. Such a strategy would safeguard India’s national interest while opportunistically leveraging China to advance India’s techno-economic interests.

1. Introduction

The internet came to China in 1994, only five years after the Tiananmen Square protests. The Communist Party of China (CPC) was concerned about foreign interference and ideological subversion encapsulated by liberal ideas such as the “free and open internet”. It responded by doubling down on digital sovereignty—the idea that just as a nation’s physical borders are protected, so must the digital borders be controlled by the State. In 2000, Bill Clinton famously remarked that controlling the internet was like “nailing jello to a wall” and couldn’t be done. “Liberty will spread by cell phone and phone modem”, he proclaimed. “Imagine how much it could change China.”1

Three decades later, the CPC has employed its ‘Great Firewall’ to limit access to foreign media and platforms, maintain control and oversight over the domestic flow of information, and crack down on dissent or any content it deems detrimental to its interests. Yet, China’s impressive technological rise has continued. Western analysts who posited that China’s creative ingenuity and rise as a tech power would be curtailed are still searching for answers.

In 2025 alone, several significant advancements across multiple technology arenas came out of China. In the realm of artificial intelligence (AI), DeepSeek caught global attention for its open-source AI models that rival Western benchmarks for a fraction of the cost and energy consumption. At the Spring Festival Gala, China’s most watched television broadcast on the eve of the Lunar New Year, a billion Chinese were treated to a tightly choreographed dance performance of sixteen humanoid robots in sync with humans, a first in the world.2 Around the same time, China announced technical improvements in its pursuit of nuclear fusion and conducted test flights of its sixth-generation fighter jets.3

These advancements are not isolated achievements. They are a result of a robust technology ecosystem. In the 2024 Global Innovation Index (GII), a widely used benchmark to assess a nation’s S&T capabilities, China ranked 11th among 133 countries and was the only middle-income economy in the top 30. China also hosts the world’s highest number of S&T clusters, with 26 in the top 100, beating the US, which has 20 such clusters.4 Similarly, as indicated by the 2023 Nature Index, China is the global leader overall, with a significant share in natural science and health science journals.5

China is also a major player in many traditional and emerging industries, from steel and shipbuilding to high-speed rail and clean energy. It is also home to formidable tech giants such as Alibaba, Tencent, Bytedance, Huawei and Baidu. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been steadily modernising and enhancing its operational capabilities, as seen by its multi-domain intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), as well as its strides in building hypersonic weapons and submarines.6

Despite these credible achievements, it would be a mistake to believe that China is nearing technological self-sufficiency or its stated goal of digital sovereignty. A closer look at China’s technology story also throws up weaknesses. In several critical technologies, China remains well behind the West. For instance, Chinese COVID-19 vaccines such as Sinovac and Sinopharm, despite China’s zeal to mass-produce and export them, were of dubious quality and showed much lower efficacy than their Western counterparts.7 While China has made significant progress in the semiconductor industry, its firms lag behind their foreign counterparts. China still depends on foreign firms for advanced chips, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and chip design software.

The CPC has long employed an iterative and push-and-pull regulatory strategy toward China’s private sector, marked by alternating periods of increased scrutiny and subsequent easing. However, Beijing’s crackdown on the private sector in 2021 was an unprecedented act of self-harm and a startling case of State overreach. It wiped out billions of dollars of market cap from these firms. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the country has since suffered, further worsened by geopolitical uncertainties triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and US-China tensions.

There are other signs that all is not well. Xi Jinping’s tightening control over political leadership has seen wide-scale anti-corruption measures implemented and several tech ministers purged. Amidst a declining economy, a high unemployment rate, and an ageing population, it would be unwise to assess China’s S&T future by merely projecting linearly from the present. Since authoritarian regimes must put on a brave face even when they are in deep trouble, their weaknesses remain subterranean.

Given the conflicting and paradoxical developments thus far, studying China’s technological rise is a worthy exercise. Further, given that technology is a key determinant of national power, this exercise is also helpful from the Indian national interest perspective. Drawing from research by several top scholars, this chapter assesses the past, present, and future of China’s tech ecosystem.

The chapter plan is as follows. Section two details the key ingredients of China’s technological rise over the past decades. It goes beyond simplistic explanations for China’s capabilities and details the interplay of foundational factors that have propelled China’s growth. Section three zooms in on the period since Xi Jinping assumed power. This period has been marked by a significant transformation in China’s posturing to the world. This has, in turn, changed the world’s response to China to greater scrutiny, distrust, and de-risking - all of which warrant close attention. Section four examines the confluence of structural weaknesses and emerging challenges of the Chinese S&T ecosystem and assesses the possible direction this ecosystem may take. Finally, section five concludes with recommendations for India and provides a calibrated strategy to counter China’s threat while advancing India’s interests.

2. Ingredients of China’s Technological Rise

Making sense of China’s technological rise is a medium-scale enterprise in its own right. Three explanations are commonly cited for China’s success: State capitalism, forced technology transfer, and IP theft. While each of these factors had a role to play, none of them—or even all of them together—fully explain the scale and speed of China’s rise. Let’s get these common explanations out of the way first.

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes commercial economic activity, often by nationalising means of production under state-owned enterprises (SOE). Claims abound that this mechanism has been central to China’s technological development. However, this view discounts the role of China’s massive private sector, a competitive domestic economy—monikered ‘Hunger Games capitalism’—and an enabling environment for experimentation and rapid iterations, which are engines of China’s technological advancements.

The narrative of forced technology transfers from foreign firms ignores China’s ability to absorb, adapt and improve upon imported technology, and to build a broad-based foundation upon which Chinese firms have evolved from imitators of low-cost rip-offs to innovators of high-tech products. After all, technology transfer is not just about getting access to a few files and products, but is a complex process undergirded by domestic capabilities.

Similarly, several instances of IP theft and industrial espionage by Chinese firms have been documented, like the notorious case of a Chinese national found guilty of stealing genetically-modified corn.8 But this narrative doesn’t account for genuine breakthroughs in other domains without credible evidence of IP theft. China now leads in global patent filings and has become a top contributor to scientific research across multiple high-tech sectors.

For the above reasons, we look beyond these simple explanations and situate China’s technological developments as a combination of fundamental factors (ingredients) and specific government policies. The theory of change we propose is as follows: the fundamental factors were the ingredients, while specific government policies were the recipes that converted the ingredients into a delectable dish. This section details these ingredients and recipes.

2.1 High Investment in Capabilities and Infrastructure

China’s focus on human capital has played a crucial role in developing its technology ecosystem. A comparison of India and China in this regard is instructive. At both primary and secondary levels, India had more enrolled students than China at the start of the twentieth century. But over time, China closed the gap and left India behind. China’s focus on primary education preceded communism. By the time Deng opened the economy, it had a large, literate workforce eager to escape the tyranny of agriculture. Despite the prevalence of cultural norms against women in both countries, higher female literacy rates also meant that more women in China were willing to defy patriarchal norms.9

By 1980, approximately 33 per cent of the Chinese population over 25 years of age had no formal schooling. This figure fell to 8.2 per cent by 2010 in China, compared to 72.5 per cent and 42 per cent in India in the same period. By 2010, the average years of schooling among the Chinese population was 7.5 years, significantly higher than 4.4 years in India.10

In recent years, Gross Expenditure in R&D (GERD) in China has consistently exceeded 2 per cent of GDP. One of the significant recent changes in R&D spending has been the sources of this funding. Businesses, including state-owned enterprises, provided 70 per cent of R&D investment in 2016, compared to 30 per cent in 1995, when government departments, elite research institutions and other organisations accounted for the bulk of funding.11

The Chinese government also made substantial investments in infrastructure. This includes transportation networks - roads, railways, air transportation, telecom, energy, and industrial materials such as steel. Chinese government investment in telecommunications, transportation, and electricity infrastructure was consistently between six and ten per cent of GDP during the 1980s and 90s. All of these enabled the growth of a grand industrial economy.12

2.2 State Focus

China has a distinctly top-down approach to technology governance. This contrasts with many countries, including the US, which have a more market-driven, bottom-up model, with the State as an enabler and regulator.

S&T ranks highly among the priorities for China’s top political leadership, who have viewed technology self-sufficiency and indigenous innovation as critical to national security. Technology is considered a key pillar of China’s National Comprehensive Power. China’s R&D spending has increased from a 4% share of global expenditure in 2000 to 26% in 2023 and is now the second largest in the world after the US.13 Reports suggest that China may now lead in global public R&D spending in absolute terms, although this is difficult to confirm conclusively.

China pursues what’s been called an ‘all-of-the-above’ and ‘whole-of-nation’ approach—a sophisticated range of policy instruments to acquire technology, build its industrial base and achieve global leadership. These are active and coordinated efforts across multiple levels of the government with the inclusion of research centres and universities, state-owned enterprises and government guidance funds (GGFs), blurring the lines between civilian and military entities, and include a wide range of measures such as selective protectionism, joint ventures (JVs) with foreign firms, cheap credit via state bank loans, land policy and infrastructure support, and strategic investments in foreign countries.

Through the Selective Authoritarian Mobilisation and Innovation (SAMI) Model, as described by Tai Ming Cheung, a long-time analyst of China’s defence and economy, China’s political economy can align the incentives of influential stakeholders. Through a centralised and top-down approach (‘Authoritarian’), the Chinese government picks a few projects for fast-tracking in long-term S&T goals (‘Selectivity’). It is able to ‘mobilise’ vast material, human and institutional resources required to support these projects. The first three elements address the political, organisational, and decision-making aspects, while the fourth component of innovation refers to different strategies to push innovation, such as absorption, adaptation, and re-innovation.14

State focus is not the same as state capitalism. Once the state outlines ambitious priorities at the central level, these initiatives cascade through China’s single-party, cadre system, where Beijing’s directives translate into a flurry of bureaucratic and private-sector activity. This trickling down of a national policy to the provincial and local government bureaucracy mobilises vast amounts of state capacity and capital towards a specific goal, but comes at the cost of wastage and inefficiency, corruption, mismanagement, and structural overcapacity. Sometimes, competition among local governments also allows policy experiments to play out, which are then incorporated into national goals.

For instance, when the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan was unveiled in 2017 with the goal of making China the globally leading innovation centre for AI by 2030, multiple local and provincial governments, now spurred to action and keen to outdo one another, released their own AI plans. Their targets cumulatively exceeded the already ambitious national targets, with even the economically weaker northeastern provinces jumping on the AI bandwagon.15

A specific policy instrument governments deploy is the Government Guidance Fund (GGF). Such funds mobilise large amounts of both public and private capital towards national strategic goals while ensuring financial returns for their investors. They offer patient capital to emerging and strategic sectors and leverage market discipline and expertise for government priorities.

Despite its shortcomings, this model allowed for iteration through a trial-and-error process and to double down on what works. The State’s political ability to fail, accepting inefficiency as a feature rather than a bug, has contributed to China’s success in a few sectors.

2.3 Learning from Others

Another ingredient is China’s long history of learning from others. The Self-Strengthening Movement of the 19th century, initiated by the Qing dynasty officials to modernise China’s military, industry and education by incorporating technologies from the US and Germany, is noteworthy for its timing. It came amidst hostile relations with the Western powers after humiliating defeats for China in the Opium Wars. It was justified by the rhetoric of using “Western means for Eastern ends”.16

Yet another instance of learning was exemplified by Deng’s visit to Japan in 1978-1979. Inspired by Japan’s post-war economic transformation, Deng said to his hosts, “Now our positions as student and teacher are reversed.”17 Despite the persistence of historical tensions stemming from Japanese imperialism during World War 2, the visit symbolises the CPC’s pragmatic approach towards technology. Post the visit, Chinese student migration to Japan resumed after three decades, and exchange programmes were set up to learn from Japan’s adaptation of Western civilisation and rapid modernisation.

In recent decades, R&D investments in China have focused on near-commercialisation rather than early-stage research. The latter is preferred to be obtained via technology transfer, indicative of the same pragmatic attitude.

2.4 Foreign Technology Acquisition

Foreign firms have been key to China’s development of technical know-how, industrial base and eventual rise to global competition. While other East Asian powers could utilise their political alignment with the West to secure technology transfers easily, China had to rely on foreign direct investment, a more complex pathway. FDI to China in 2002 was 28 times higher than in 1986, and its share of global FDI inflows rose from 1.4% to 8.1% over the same period.18 In 1990, the other Southeast Asian countries attracted four times as much FDI as China; by 2002, that situation was reversed. FDI inflows into China peaked as a percentage of its GDP at 6.2% in 1993 and steadily rose in absolute numbers until 2021.19

Through joint ventures (JVs) and partnerships with Chinese firms in what is called the “Trading Market for Technology” paradigm, foreign firms that wish to access China’s large domestic market are required to establish manufacturing facilities and sometimes even research centres in China, training a generation of Chinese researchers and engineers in the process. What is unique about China here is its motivation and investment in the scientific foundation necessary to “bring in a technology, absorb it and then re-innovate” on top of it.20

A revealing example is the case of high-speed railways. In 2004, China’s Ministry of Railways arranged JVs of Chinese firms with foreign train manufacturers such as Siemens and Alstom that were facing maturing markets with little potential for growth. As Kyle Chan, a researcher specialising in Chinese industrial policy, points out, these firms were promised a once-in-a-century market in exchange for manufacturing know-how and technology sharing. To assimilate the technology, China not only had companies in train manufacturing and railway construction but also research centres and national laboratories focused on high-speed rail. In the years since, China merged its train makers into a single state-run entity, CRRC, which has now become the top global competitor to its former Western and Japanese partners. The story is similar across multiple other sectors. Tesla’s Gigafactory in China eventually contributed to the Chinese EV industry, including battery giant CATL. Apple helped spin off a wave of Chinese mobile manufacturers, including Vivo and Oppo.21 The expertise gained from JVs with Belgian firms later helped develop domestic telecom companies like ZTE and Huawei.22

Different strategies of industrial espionage helped accelerate this. Many went largely unnoticed by the countries providing the technology transfers because China was not seen as a threat capable of rivalling their firms. There was also a somewhat naive belief that China would make way for genuine collaborations as its own industries matured, as encapsulated by the Chinese slogan of “standing on the shoulders of giants”.23

In any case, Western firms have been happy to leverage China’s low-cost and nimble manufacturing base and outsource environmental externalities to focus instead on the parts of the value chain believed to make higher profits—design, research and development, and marketing of the final product. In this process of comparative advantage and global supply chains, Western companies have earned tremendous profits. In the meantime, China’s high-quality talent pool with deep process knowledge gained on the factory floor, in dense networks of industrial clusters, transformed what was earlier considered a mass manufacturer of low-quality goods into a high-tech power.24

The geopolitical environment was also generally favourable, with minimum friction to China’s technological integration with the Western markets. High-tech sectors were not as securitised as in more recent times, and Chinese firms benefited from access to foreign research, patents, and global standards. This helped China leapfrog in its innovation journey and compete globally despite being a late entrant.

Shenzhen is a striking example. Chosen in 1980 as one of the five Special Economic Zones (SEZs) under the Deng Xiaoping government, it has since transitioned from a fishing town to what is today considered the Silicon Valley of the East. Supported by an ecosystem of sharing and collaboration with little regard for IP and operating in a regulatory grey zone, Shenzhen began by producing ‘Shanzhai’, a term for Chinese counterfeit electronic items, usually rip-offs of foreign electronic brands, such as ‘Nokir’ and ‘Samsing’. At some point, Chinese firms, spurred by increasing competition amongst themselves, moved from copying foreign firms to copying one another, in the process producing innovative designs often better than their Western counterparts. Xiaomi is an example of a company that emerged from this ecosystem.25 Today, Shenzhen is a bustling innovation hub where R&D labs are colocated with manufacturing facilities. With university researchers, entrepreneurs, investors, and high-end engineers in tight networks, Shenzhen is a centre of high-tech hardware, with novel electronic products such as consumer drones and virtual reality headsets.

However, for the foreign firms that have traded their technology for short-term profits, the trade-offs are real.26 As Chinese firms gain competitiveness, foreign firms faced a double whammy—being squeezed out of China’s large domestic market and then challenged in their global markets. As Michael Dunne, a veteran in China’s automotive market, points out, the automobile industry is currently undergoing this shift.27

2.5 Leveraging High-tech Talent

China is unique in the scale and focus with which it has sought to leverage high-tech talent, both Chinese-origin and foreign, to advance its national goals. With the economic reforms, Chinese students were sent abroad, and the government, through initiatives such as the ‘Young Thousand Talents Programme’ launched in 2008, attracted foreign researchers into China with generous packages, startup funds, and internationally competitive salaries.28

And yet, this is only one of the many talent programmes China has initiated, targeting different age groups and technology areas. Other central government programs focused on fostering talent include China’s National Medium and Long-term Talent Development Plan (2010–2020), The 2017 Plan to Build a National Technology Transfer System and the 2016 Planning Guide for Manufacturing Talent Development focused on importing “1000” foreign experts, including from “famous overseas companies” able to make “breakthrough” improvements. Other talent programs dedicated to developing specific talent in high-tech sectors such as biotechnology, integrated circuits (IC) and AI also exist.29

These sponsored talent programs are about more than simply increasing the hiring of global experts. They entail a highly developed ecosystem with dedicated state research and private venture capital funding, global recruitment and candidate evaluation networks, overseas experts’ databases and numerous other supporting organisations.30

Importantly, the goal is not always to get people back to China. It is about getting them to serve China even if they are overseas. Hannas et. al document that Chinese researchers abroad are told that what they are doing benefits not only one’s “small self” but a “larger self”—namely, one’s homeland and kin. “Serve the Motherland” initiatives encourage Chinese overseas to accept part-time work in coordinating research and commercialising technology in China. Events are organised to connect overseas talent with Chinese enterprises for research collaborations. Seemingly, non-profit organisations such as the Federation of Chinese Professional Associations in Europe (FCPAE) and private individuals are co-opted to achieve party goals and assist with talent recruitment and technology acquisition.31 Another policy instrument is the setting up of “Offshore Innovation and Entrepreneurial Bases for Overseas Professionals” that operate on a “hub and spoke model” - a base in China incubates and commercialises innovative ideas sourced from a network of offshore centres in foreign countries. By 2019, the Chengdu High-Tech Industrial Zone had 31 offshore centres spread across Japan, Europe, the US, and South Korea.32

Such “overseas workstations”, along with the larger transnational, ethnic Chinese technology community, have also been instrumental in binding foreign firms to China. Shared ethnic ties have encouraged ethnic Chinese foreign technology firms to locate their core technology activities in China, helping with investment inflows and technology absorption, even as foreign firms have been slower to commit resources to China.

2.6 The Tech-Savvy Chinese Consumer

The dynamic, tech-savvy and highly demanding Chinese consumer is an interesting but often underappreciated facet of China’s engineering breakthroughs.

According to the Lived Change Index, which uses lifetime GDP to track the economic change people have lived through, between 1990 and 2019, China’s per capita GDP grew by 32 times, the highest of the world’s top 40 economies. This means that China was changing faster—economically, socially, and technologically—than any other place on earth.33 Not only is the physical landscape around the consumer changing, but so is the mental landscape, leading to a hyper-adaptive and hyper-adoptive consumer base of more than a billion users, which the technology platforms can experiment with and improve amidst gruelling competition.

This has led to several consumer tech use cases unique to China that haven’t taken off in other countries. Social commerce—e-commerce interlaced with social media—is one example of Chinese firms pioneering world-class engagement algorithms and business models such as live streaming and group discounts for an enhanced consumer experience. China also has several super apps that dominate its digital landscape by combining e-commerce, digital payments, social media and lifestyle services in one platform.

2.7 Some Caveats

As detailed in this section, six foundational factors and specific government policies powered China’s ascent as a technology power. However, it’s essential to understand the trade-offs that China made.

For example, the state’s focus on technology has come at the cost of a spectacular waste of resources. As per a National Development and Reform Commission report, in the five years since 2009, half of all investments have been ineffective, leading to a wastage of nearly $6.9 trillion.34 Government subsidies tend to be directed toward less productive firms for political and social reasons rather than those with the potential for innovation and growth. The disbursement of government funds continues to make these firms dependent on them, furthering their inefficient operations and providing little market incentives for change. Also, for every example of an industry that has gained global leadership from Chinese subsidies—EVs, batteries, solar panels—there are others that have underperformed, such as the semiconductor industry or China’s aspirations to build indigenous commercial jets.

China’s SOEs are also riddled with mismanagement, corruption and inefficiency, and despite significant efforts to make national champions out of them, they have hardly been able to become technology leaders. Doug Fuller, a long-time analyst specialising in China’s techno-political economy, refers to these SOEs as ‘Paper Tigers’—an entity that appears to be threatening but in reality, wields no real power—a metaphor popularised by Mao Zedong in his description of the US atom bomb.35

As for GGFs, despite being hinged on market incentives, they also suffer from similar burdens. As of 2021, there were at least 1800 such funds at different levels of the government, indicative of their redundancy and inefficiency to the point of crowding out private capital. Many of these funds are also run by bureaucrats instead of venture capitalists with deep market or technical acumen and have often been riddled with corruption. Many GGFs are also unable to pool the funding they initially aim to raise. Despite their purported focus on long-term, early-stage high-tech sectors, they are repurposed to meet debt, infrastructure and more short-term and safer bets. The Chinese government has sought to reform these funds and enhance their effectiveness, but this remains an ongoing effort with structural roadblocks.36

The waste resulting from several of these government initiatives focused on supply-side incentives is evident in the scores of data centres left unutilised, abandoned farms of EV vehicles and bikes, and China’s annual production of solar panels far outstripping global installation demand.37

Similarly, concerns surrounding forced technology transfer and IP theft have made other countries more sceptical of Chinese investment and talent.38

Having looked at the core ingredients of China’s technological ecosystem, the next section analyses the changes that have taken place over the last decade.

3. Xi Jinping Upends the Status Quo

When Xi Jinping took over as China’s paramount leader in 2012, China was an increasingly powerful and prosperous economy, a force to reckon with. However, underlying vulnerabilities threatened how the Chinese story may unfold. Economic growth was beginning to taper off after a spectacular run since the 1978 reforms. The administrative State was entrenched with corruption and partisan factions. On the S&T front, China had made headway in catching up to the West but had little to show by way of original innovations. A key priority for the Xi Jinping administration was for China to avoid the middle-income trap.

In the decade since, China’s S&T ecosystem under Xi has witnessed four significant changes: new policy initiatives, China’s changed geopolitical posture, higher domestic capital flows coupled with increased corruption, and intensified State control. These moves have, in turn, changed the world’s perception of China. This section examines these recent developments in detail.

3.1 New (or Pivoted) Policy Initiatives

As in other areas of the Chinese economy, Xi Jinping pushed the Chinese S&T ecosystem and its policy architecture into a massive overdrive. Xi Jinping’s idea of a ‘Chinese Dream’ and ‘national rejuvenation’ is rooted in technological supremacy. Among the first major initiatives he undertook after taking leadership of the CPC was the Innovation-Driven Development Strategy (IDDS) - a highly ambitious and complex undertaking with a focus on indigenous innovation, reform in technological structures, close integration of S&T with economic development as well as a seamless civilian and military integration, with the final goal of positioning China as a strong global innovation power by 2050. IDDS adopts a SAMI model of targeting core and emerging technologies and is the conceptual framework behind multiple initiatives and plans such as the Made in China 2025 and 13th Five-Year S&T Innovation Plan.39

IDDS is particularly notable for its vision of making China an “innovative nation” by 2020, a “leading innovative nation” by 2030, and ultimately a technological superpower by 2050. Xi has spoken about the urgency of China avoiding becoming the “technological vassal of other countries” and said that the national innovation system needs to be built up. A key feature of the IDDS is international S&T exchanges and cooperation despite its push for self-resiliency. Tai Ming Cheung remarks that the strategy is “state-directed but market-funded, globally engaged but framed by techno-nationalist motivations”. Meanwhile, China’s R&D expenditure continues to grow, and in 2020, it came close to 2.5% of GDP, as targeted by the IDDS.40

Another important initiative undertaken by Xi Jinping is the Military-Civil Fusion (MCF) strategy, elevated to be a national priority in 2015 and defined as a developmental strategy. The latest pivot of earlier attempts to integrate the civilian and military industries, the MCF promotes dual-use technologies and a two-way collaboration for China’s economic growth and national security.

3.2 Increased Capital Inflow and Corruption

Another change under Xi is the increased funding flowing into the system, and with that, increased corruption.

For instance, China’s National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, commonly called the semiconductor ‘Big Fund’, has had three iterations so far, starting in 2014. The latest iteration announced in 2024 was a massive $47.5 billion in size.41 The goals of the Big Fund were for China to develop capabilities across the semiconductor value chain and a higher degree of self-sufficiency in chip production. To ensure a market for the sector, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has urged Chinese EV carmakers to procure 25% of their chips from domestic sources by 2025, even though they are costlier than foreign alternatives by up to 30%.42 However, in 2022, China’s anti-corruption agency led a series of investigations into the Big Fund, culminating in the arrest of several high-ranking officials, including Ding Winmu, the head of the fund.43 That is not all. More than 14,000 semiconductor companies, many likely to have jumped on the bandwagon in light of the increased governmental prioritisation in the sector, went out of business in 2024 alone, with a similarly bleak picture for the previous few years.44

More generally, Xi’s tenure has seen an unprecedented rise in anti-corruption measures across sectors, many of which are believed to be politically motivated to seal his own position. In the tech domain, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has seen a shake-up, with two tech ministers purged, namely Xiao Yaqing in 2022 and Jin Zhuanglong in 2025.45

3.3 More Centralised Control

Since assuming power, Xi Jinping has systematically shifted decision-making power from the government institutions—ministries and bureaucratic arms—to the party structures under his direct oversight. New institutions have been established to bring disparate agencies under centralised, unified control.

One striking case study is with regard to internet governance early on in Xi’s tenure. China created high-level and centralised bodies such as the Central Leading Group for Cybersecurity and Informatisation, and later rebranded the State Internet Information Office as the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). This has had downstream effects on the autonomy and relative vibrancy of online debate and communications, with the Xi administration methodically closing channels for public deliberation. The CPC, which previously disseminated its propaganda through state-owned media, has also ventured into actively producing its messaging online.46

A key development in systemic overhaul and centralisation of power is the definitive restructuring of China’s S&T governance that happened in 2023. A new superseding body, the Central Science and Tech Commission, was established for strategic planning and policy setting in S&T, taking over from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), which is now relegated to more administrative functions.47 The choice of the commission’s director - Vice Premier Ding Xuixiang - is interesting, too. Being a trained engineer who previously spent time as a materials science researcher and administrator before moving to politics as a deputy director of the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission in 1999, he brings scientific management skills to the commission. Ding is also believed to be extremely close to and trusted by Xi, marking the importance of the commission to China’s national goals.

Next, Xi’s tightening control over the party’s cadre system also affects local governments. Previously, while subject to central government oversight, local governments enjoyed some decision-making autonomy. Yuen Yuen Ang, a leading scholar of the Chinese political economy, introduced the concept of ‘Directed improvisation’ or ‘decentralised experimentation’ to explain China’s mechanism of adaptive governance. According to her, this was a key approach to balance broad central guidance with flexibility for implementation and interpretation at the local government level, allowing local governments the freedom to experiment, improvise and adapt to their specific contexts.48 However, under Xi, this is increasingly not the case. With central control of local finances and increased political oversight and scrutiny of the bureaucracy, there is a paralysis of action in the cadres. The ability of local governments to contribute toward a decentralised model of S&T development is markedly reducing.

The desire for self-sufficiency has resulted in local governments focusing on a narrower set of product lines. For example, the drive to localise the entire supply chain for semiconductors is divorced from market-based demand and the comparative advantages of the Chinese industry. The “Big Fund” began in 2014, intending to build a self-sufficient semiconductor industry. Drawing on this, many local governments indiscriminately poured money into chip-making firms. Ten years later, China has not mastered the production of advanced chips. Nevertheless, many firms continue to milk local governments for funding.

Finally, control over firms has increased in various ways. The CPC has always been wary of alternative power structures that can threaten its standing. Specifically, the Xi Jinping administration’s crackdown on the Chinese private sector in 2020 is noteworthy for its ideological commitment.

Following a controversial speech where Jack Ma, the founder of the Alibaba group, criticised China’s financial regulators and banks, the initial public offering of Ant Group, the fintech affiliate of Alibaba, which would have been the largest in the world, was quashed. Several controls and bans on the private sector followed. A broader regulatory overhaul was imposed on the firms’ monopolistic behaviour, data security and the societal impact of these platforms. This overnight wiped away billions of dollars of market value from the Chinese ‘virtual economy’, such as its ed-tech, mobility, e-commerce and gaming platforms.

China enacted a range of interrelated national security laws that impose ill-defined and open-ended obligations on individuals and businesses to support the Chinese State in data collection, intelligence operations and national security measures if called upon. Among these laws are the Counter Espionage Law (2014), National Security Law (2015), Counter Terrorism Law (2015), Cybersecurity Law (2016), National Intelligence Law (2017), Encryption Law (2019), and the draft Data Security Law.49 These laws give unfettered access to the state intelligence agencies to a company’s IP, business facilities, sensitive data, personnel, communications equipment and more.

Xi has held a dismissive view of consumer technology, comparing it to “spiritual opium”, a reference to the opium wars that led China into the Century of Humiliation. This is based on his view that consumer entertainment and digital apps don’t contribute to a nation’s “real economy” or hard “national power” and, in fact, threaten the “common prosperity” and social stability of the people. The “barbaric” growth and “disorderly expansion of capital” in the internet economy were believed to be antithetical to the CPC’s standing.50

3.4 Geopolitical Perceptions Have Changed

In 2018, a Bloomberg investigation report on Super Micro Computer Inc. raised public awareness of the vulnerabilities in the global firmware and hardware supply chains stemming from contracting manufacturing to China. The report revealed that as far back as 2010, the US Department of Defence had discovered that thousands of its servers supplied by SuperMicro were exfiltrating network data back to China. These chips were traced back to China, where a unit of the PLA had meddled with the operations of the private company.51 Though the Bloomberg report has its share of doubters, it set the narrative that hardware products assembled in China are susceptible to malicious intrusions. Such cases, coupled with Beijing’s expansionist, irredentist, and aggressive stance across multiple domains, strengthened the resolve of countries to de-risk from China.

The current geopolitical tensions and denial regime may be traced back to the US tech export controls initially applied with a limited scope on the telecommunication giant ZTE for violating US sanctions in 2018.52 Huawei’s 5G infrastructure networks increasingly came under the scrutiny of the US, Australian, Indian, and UK governments for national security concerns of surveillance and espionage by the Chinese government.53

This approach initially continued under the Biden administration. The then National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan called it a “small yard, high fence” approach, meaning that in a narrow set of advanced technologies, Chinese firms will be resisted with the full force of the American State. In other areas, the approach will be business-as-usual. For example, American export controls on China’s semiconductor industry were to apply only to the most advanced semiconductors that could have military uses. By the end of the Biden administration, this approach had escalated to a much broader range of export controls, targeting a wide range of high-tech products, such as high-end AI chips, advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and biotech laboratory equipment.

Amidst these escalating tensions, there has also been a rise in the decoupling of research collaborations between Western and Chinese institutions.54 The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 restricts National Science Foundation R&D funding to institutions that host or support Confucius Institutes. Chinese-origin researchers in the US, Japan, and Australia face higher scrutiny if their work concerns critical technologies.

Tipping the geopolitical environment from benign to increasingly distrustful and hostile towards China is a pivotal moment for China’s S&T ecosystem. As evidenced by the wide range of export controls, decoupling in research collaborations and heightening tensions, China is now considered a threat and rival to the global power order, unlike in the past.

With this understanding, we now turn to the next section to analyse this ecosystem’s potential future trajectory.

4. Where is this ecosystem headed?

In our assessment, while China will continue to capture global attention for its technological innovations and breakthroughs over this decade, it is unlikely to sustain these over the long term. We say this because the ingredients and recipes that made China a technological superpower no longer apply and have undergone significant changes, as described in Section four. Multiple emerging challenges and structural problems within the Chinese S&T ecosystem support this claim. We detail them in this section, starting with our immediate and short-term prognoses.

4.1 Escalating Geopolitical Tensions and ‘Creative Insecurity’

China has reacted to external pressure from the denial regime with swift retaliatory measures and intimidation. It has gone beyond what previously used to be a symbolic stance against US defence companies that Chinese firms didn’t have much operations with anyway. China, too, maintains an Unreliable Entity List, a countersanctions tool established after the 2019 addition of Huawei to the US entity list. Specifically prominent are China’s licensing requirements for the export of critical minerals such as germanium, gallium, antimony, and graphite, which are meant to exploit China’s dominance in the processing part of the value chain of these minerals. With less leverage between the two, Chinese competition agencies have also resorted to intimidating US companies operating in China, such as NVIDIA, Google, Apple, and Chinese consultancies working with foreign multinationals.55

The increased securitisation of technology and the rampant export controls on China have exposed the dependence and vulnerability of Chinese firms to foreign technology. While previous attempts by China to prioritise indigenous innovation in high-tech saw ebbs and flows with a flurry of government activity that eventually lost focus, it appears to be different this time. This can be explained by ‘creative insecurity’, as posited by Mark Taylor, a researcher specialising in the political economy of S&T innovations and understanding why some nations excel at S&T while others do not. In his book, The Politics of Innovation, Taylor argues that significant external threats make governments prioritise innovation policies, likely creating non-linear breakthroughs.56 Several Chinese firms are already aligning with the State’s indigenisation and self-sufficiency agenda, which will likely continue this decade. For example, upon being added to the US entity list in 2019, Huawei lost access to Google’s license for Android electronic items. This prompted the development of HarmonyOS, Huawei’s own operating system.57

China has been responding with asymmetric options on the technology front. DeepSeek is one example of clever technical optimisations that arose from the need to achieve more with less computing capacity. In response to the semiconductor export controls, China established the RISC-V Industry Consortium to promote the adoption of open-source chip architecture. As has been pointed out by several analysts, China has been playing both sides—pushing for more control at home while advocating for more openness in the international arena.58

The Chinese government’s retaliatory response to external pressure has further escalated and raised the stakes of geopolitical tensions. This, while increasingly cutting China’s international linkages to global talent and knowledge flows, will allow China to benefit from ‘creative insecurity’ in the short term. China’s renewed efforts at indigenisation, self-sufficiency, and asymmetric approaches to counter these pressures will likely result in the announcement of breakthroughs across multiple technology arenas.

However, persistent and sustained geopolitical tensions will jeopardise the sources of China’s innovation strengths, and cripple its rise over a longer term.

4.2 The Cost of Geopolitical Backlash

China’s technological advancements were hardly built by being insular to the world. They are a result of three decades of persistent international linkages. Without a favourable geopolitical environment that allowed the flow of capital, talent, and ideas into China, the country’s innovation ecosystem would not have been possible. Technology transfers and JVs with foreign firms, supported by China’s embedded presence in the global production networks and research collaborations with the West, were key to this process.

However, these ingredients that made China’s success possible no longer apply to the same extent today. As detailed in the previous section, attempts to diversify away from China in trade and investments, research collaborations, and talent exchanges are genuine, if not comprehensive and coordinated. A less open world will hurt China’s aspirations to advance technologically. China’s trade surplus and its position as the manufacturing hub of the world, which provided a key foundation for its S&T advancements to eventually emerge, are not being looked upon kindly by countries that have had their domestic industries decimated by the “China shock”. Chinese companies got to world-class standards by continuously sparring with the best companies in the world. Their incentive to innovate is likely to decrease in a fragmented world as more and more countries raise barriers to Chinese products in their legislation. As will their ability to invest in R&D, amidst crunched profit margins and narrower market reach.

4.3 Private Sector Woes - Declining Economy, Regulatory Challenges and Capital Flight

The private sector in China has been its engine for technological advancements, a sharp contrast to the inefficiencies of China’s SOEs. However, it is now facing a double whammy - a hostile international environment and a slowing domestic economy stalled by structural problems. These domestic troubles include the implosion in the property and real estate sector, high unemployment rate (as of October 2024, 17% youth unemployment rate - among those aged 16 to 24, excluding students), an ageing population, Beijing’s propensity for wasteful supply-side incentives and subsidies coupled with China’s low domestic consumption and demand.59

The Xi Jinping administration has responded to these structural problems with a renewed focus on ‘New Quality Productive Forces’, a narrow set of emerging and high-tech sectors to spur consistent economic growth. Despite much of the investment being directed to these sectors, their ability to absorb the unemployment rate, stimulate domestic demand and turn the tide of the economy appears to be low, as compared to more traditional and legacy industries. The private sector is also still reeling from the effects of the 2020 regulatory overhaul and its arbitrary investigations, fines and charges that overturned the sector’s very foundations. The tech sector has already announced a reduction in R&D spending, along with hiring freezes and universal pay cuts. Huawei’s founder, too, had announced such a forecast for the firm in 2022.60

Since the 2020 crackdowns, a sticky problem for the Chinese economy has been ‘capital flight’ - low FDI and FII inflows, which is further compounding the problem. Venture capital funding has been cut in half and is unlikely to see a comeback anytime soon.61

It is in this context of a dramatic decline of the private sector that Xi Jinping reached out to the domestic private sector entrepreneurs in a high-level symposium, a month after tech billionaires flanked Trump at his inauguration. However, Xi Jinping’s speeches suggest it is unlikely that the ideological instincts that led to the earlier crackdown have gone away. Unless supplemented by key policy changes or ideological pivots on the part of the administration, the hitherto broken trust between the party and the private sector is unlikely to mend. Hence, China is less likely to be able to persistently sustain its private sector breakthroughs, despite the recent success of firms like DeepSeek.

4.4 Local Government Fiscal Stress

China’s declining economy will also affect its government’s S&T funding. Local governments accounted for about two-thirds of total government S&T spending in 2022. Capital expenditures such as new infrastructure projects and GGFs are financed through a special government fund budget that is dependent on land revenues and debt, which have been under severe strain since the property market crash, thereby jeopardising the stability of this funding mechanism.

Local governments are already facing fiscal crunches, with their revenue share as a percentage of the GDP consistently falling, from about 12% in 2015 to 9% in 2022. They are also being spread thin across various expenditure avenues. While they face heavy debt repayment burdens, they are also being asked to spend more across a wide range of policy priorities, such as public healthcare and social systems for China’s ageing population. Funding for S&T is likely to suffer, which will have implications for early-stage R&D funded by government grants in research institutions. It is in this light that we must look at the recent announcement of a government guidance fund of a trillion yuan focused on deep tech startups with a longer horizon of twenty years, double the timelines of a typical US-based fund.62

4.5 Diffusion Deficit

According to Jeffrey Ding, a leading voice on China’s technological development and its implications for global politics, China suffers from a diffusion deficit. He argues that general-purpose technology diffusion, and not leading sector innovation, determines national power. And China has a substantial gap between its innovation and diffusion capacity. While it leads in metrics focused on a nation’s ability for novel breakthroughs, such as R&D expenditure, scientific publications and patents, it suffers from weaker processes by which new technology advances get embedded into economic processes and convert into productive growth. Drawing parallels to the innovation-centric assessments that overestimated the Soviet Union’s S&T ecosystem in the 1970s, he categorically states that China’s diffusion metrics indicate it would be less likely to sustain its technological advancements.63

China’s weak diffusion capacity is evident in multiple ways. Firstly, decomposing the 2020 GII reveals a glaring gap between China’s global standing in the innovation capacity subindex and its diffusion capacity subindex. In the former, China’s standing at 13.8 is similar to that of the US at 11.9. However, for the diffusion-capacity subindex, China’s average ranking of 47.2 is several steps behind the US’s average ranking of 26.9.64

Secondly, the connective tissue and linkages between a nation’s industry and academia, an indicator of its diffusion capacity, also seem to be weak in China compared to the US, as measured by academia-corporate hybrid publications. In fact, Xinhua, China’s official state news agency, reported in 2019 that the lack of technical exchanges between China’s universities and the industry was one of five key weaknesses of the Chinese AI talent ecosystem.65 Additionally, only 3.9% of university-originated invention patents found their way to industrialisation, as reported by a 2022 Chinese government survey.66

Thirdly, China lags significantly behind the US in the adoption rate of information and communications technologies. While some use cases, such as consumer-facing technologies and high-speed railways, saw a large-scale deployment, Chinese businesses have been slower to embrace digitisation, as measured by adoption rates of cloud computing, smart sensors, and other key industrial software.67

All of these point to China’s weak institutional capabilities and its inability for resilience in the face of external pressure and other challenges. ### 4.6 Summing Up

An environment like this, with multiple coterminous roadblocks, will surely impede China’s success story.

All of this might seem incongruous with the news reporting on China’s S&T prowess, which we believe should be interpreted cautiously. Much journalism about China’s global dominance and takeover of critical and strategic technologies is overblown. Several news reports consistently exaggerate early-stage research findings from China, politicise and sensationalise scientific endeavours by private players as initiatives of the Chinese government, stripping them of any agency, exoticising China’s S&T ecosystem in the process and furthering the narrative of fear and suspicion for the Chinese State.68

To summarise, there are multiple emerging challenges and structural weaknesses in China’s S&T ecosystem. A challenging external environment laden with geopolitical tensions and attempts to diversify away from China, a slowing domestic economy with a reduced appetite for risk capital, and weaker institutional capabilities mean that the ecosystem lacks sufficient resilience to overcome its difficulties. This is not to say that all this will force China to submit to external pressure or dismiss it into oblivion, far from it. Evidence suggests that it has a critical mass of indigenous capability in multiple technology arenas to continue developing, albeit at a lower pace.

As this section shows, China’s ability to support its research infrastructure and mobilise talent to take risks, work on cutting-edge innovations and adjacent critical sectors is likely to decline over the next decade. Hence, China is unlikely to take over the US as a global technology powerhouse anytime soon. The gap with the US is only likely to widen further.

5. Implications and recommendations for India

This section studies the implications of China’s tech trajectory for India.

India runs a $100 billion trade deficit with China and is heavily dependent on China for electronics components and pharmaceuticals, with a staggering 56% and 43.5% dependence on China in FY24, respectively.69 The more India exports to the US, the EU and the UK, the relationships with which it has trade surpluses, the more it will depend on China for intermediate products.

The period between 2011 and 2016 saw robust bilateral engagements with China emerging as one of India’s fastest-growing sources of FDI. In 2011, the total Chinese investment in India was $102 million, which quickly shot up to over a billion dollars by 2016. While the official Indian and Chinese statistics differ on cumulative figures, the actual, on-the-ground figures are likely to have been at least three times the official numbers.70 Still, the numbers were a trickle compared to the total FDI inflow into India and China’s large FDIs into its BRI partners.

In 2014, China announced a $20 billion investment in India over five years, planned for the manufacturing and infrastructure sectors.71 The shift in Chinese investments from the manufacturing and automobile sectors to India’s high-growth digital economy between 2015 and 2017 is noteworthy. Chinese firms like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and ByteDance became significant investors in Indian startups like Paytm, Zomato, BigBasket, and Practo.

The 73-day military standoff between India and China in Doklam in 2017 marked the first major disruption to bilateral ties, changing the course of events. A growing anti-China sentiment among the Indian citizenry made policy circles view China as an unreliable partner. The crisis had economic ramifications, with China suspending the imports of Indian pharmaceuticals and cotton, and Chinese investments in India dropped by approximately 12% in 2017. Indian investments in China, too, declined by 21% during the same period. While Chinese investments in India’s startup ecosystem did not completely halt, they certainly faced greater scrutiny from both governments, India’s trade deficit with China continued to grow despite these setbacks.72 As did the widespread adoption of Chinese digital apps in India. In 2017, 18 out of the top 100 on the Google Play Store in India were Chinese, which went up to 47 in 2018.73

A clear dip in India-China ties in recent times came about with the May 2020 Galwan Valley clashes. Indian policy thinking about dependence on China definitively shifted from a private player-led economic lens to a state-led, long-term, security, and strategy lens. Pre-2020, Chinese e-commerce, technology, and telecommunications firms had an expanded presence in India. But this would quickly change.

India’s scrutiny of Chinese investments precedes the Galwan Valley clashes. In April 2020, policy changes were made such that FDI from China was restricted and needed government clearance.74 This was to prevent “bargain hunting”, as had happened in the early months of the pandemic when the People’s Bank of China bought a 1.01 per cent stake in HDFC, India’s largest private bank.75

India reacted to the Galwan crisis with intimidation and by placing blanket restrictions on Chinese firms. A press release banned over 300 Chinese social media, gaming and e-commerce platforms. Companies like Huawei and ZTE were restricted from participating in 5G trials, and tax officials raided several Chinese firms in India, alleging financial irregularities and money laundering. Chinese firms were disallowed from participating in Indian infrastructure projects, even through JVs with Indian firms. Chinese investors also faced a blanket ban on Indian micro, small and medium enterprises.

The Modi-Xi meeting at Kazan in October 2024 was yet again a strategic shift in India-China relations. The meeting provided a tactical thaw in the relationship by taking a step toward normalising the ties between both parties through a tactical disengagement agreement at LAC. More importantly, the meeting signalled that the border issue, while still unresolved, would not be allowed to dominate the relationship.

Yet, China’s actions continue to warrant caution on India’s behalf. China’s deliberate attempts to curtail India’s manufacturing are evident. Recent news reports confirm that China is blocking the sale of tunnel boring machines by a German company named Herrenknecht, which is used for vital infrastructure projects. 76 China is also actively blocking Foxconn’s Chinese employees from visiting Foxconn’s Indian production facilities to halt Apple’s China+1 move.77

Given this history of India-China ties and the prospects of China’s tech sector outlined in section four, what should India’s techno-strategic stance towards China look like?

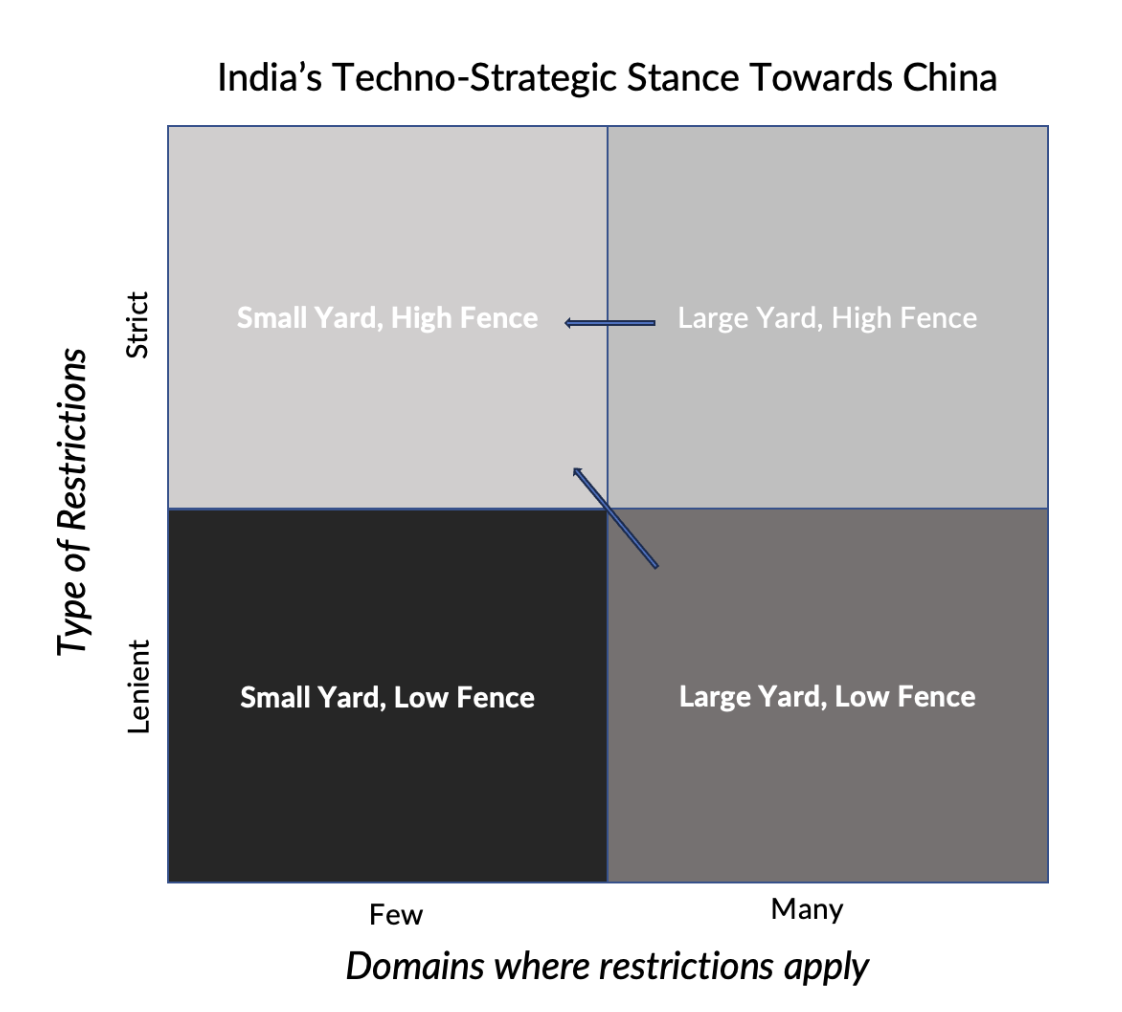

The Biden administration’s conceptualisation of a “small yard, high fence” provides a reference point. This approach (at least theoretically) meant that the US would decouple from China in narrowly defined sub-domains rather than whole sectors. For example, American export controls on China’s semiconductor industry apply only to the most advanced semiconductors and not to trailing-edge chips. We can use this approach to construct three other options, as Figure 1 below shows.

India’s strategy can be characterised as a mix of a “large yard, low fence” and “large yard, high fence” approaches. India has closed itself to Chinese technology investments and products more than the US has. For instance, Chinese EVs, TikTok, and Huawei face more barriers in India than in the US. Some of it is justified given the context. India must avoid Chinese products that could impact its cognitive infrastructure. In that sense, a ban on TikTok and restrictions on Huawei in core telecom infrastructure are explainable. In Taiwan, for example, it appears that TikTok is promoting pro-China content, softening the stance of the younger generation towards the PRC, and surveys reveal that the opposition to Taiwanese independence is highest among TikTok users in the same age group compared to non-TikTok users.78

However, there’s no reason India should be closed to investments by Chinese mobile phone firms, solar cell and wafer firms, or electric vehicle firms. Unlike the West, India has much to learn from China in these sectors, and their investments will improve the Indian ecosystem. We argue that India should adopt a “small yard, high fence” approach, too. We realise that India’s “small yard” will differ from America’s—the domains that concern India might not be the same as those in the US. Nevertheless, the approach suits Indian realities and requirements better.

This change in thinking is vital because India will continue to have external dependencies for intermediate goods, specialised equipment, international talent and critical materials even as it builds domestic capabilities. A recoupling between India and China would also help substitute India’s trade deficit with investment flows from China. Even if India does not benefit from R&D transfer, manufacturing know-how from China will only accelerate, not impede, India’s growth.

Two shifts in India’s policy thinking would be needed for India to adopt a “small yard, high fence” approach.

One is differentiating the CPC from Chinese businesses. Indeed, the CPC controlled economy means that Chinese firms have less agency than their counterparts in the US or India. It is also true that China’s aggression on the border and adversarial positions at multinational fora show that it sees a growing India as a threat, not an opportunity. However, it is also important to note that Chinese businesses—especially suppliers to other multinationals—have different incentives from those of the CPC. As the analysis in this chapter shows, Chinese companies are looking for investment opportunities given the headwinds they face. Both global and domestic demand in China remains suppressed, squeezing these firms of their profits. As global supply chains seek to diversify away from China and Chinese products increasingly face backlash in developed countries, Chinese firms would look for other developing markets. In this regard, India is a lucrative market and must leverage its advantage to attract Chinese investments in non-strategic sectors.

Take electronics manufacturing, for instance. The Apple ecosystem alone accounts for over 50 per cent of mobile exports from India. Of the 188 companies in its supplier list, 151 are Chinese or have a substantial manufacturing presence in China.79 The only way for Apple to shift a part of its supply chain to India is to get its Chinese suppliers to invest there. There is a case for loosening the 2020 FDI Rules for such domains.

Chinese investments can also give India foreign policy leverage. Economist Swaminathan Aiyar argues that “massive foreign investment is a bigger risk for the foreigner than the investee country. So, let us attract as much Chinese investment as possible, since the main risk will be theirs, not ours.” This approach is worth deliberating.

Secondly, the Indian strategic establishment needs a sharper definition of what counts as a ‘strategic’ technology. Declaring entire sectors as strategic is counterproductive. Electric vehicles, low-end chips, solar cell wafers, and mobile phones are not strategic. Data exfiltration and espionage concerns can be managed by hardware supply chain security protocols. In such domains, India must have a favourable approach towards Chinese investment.

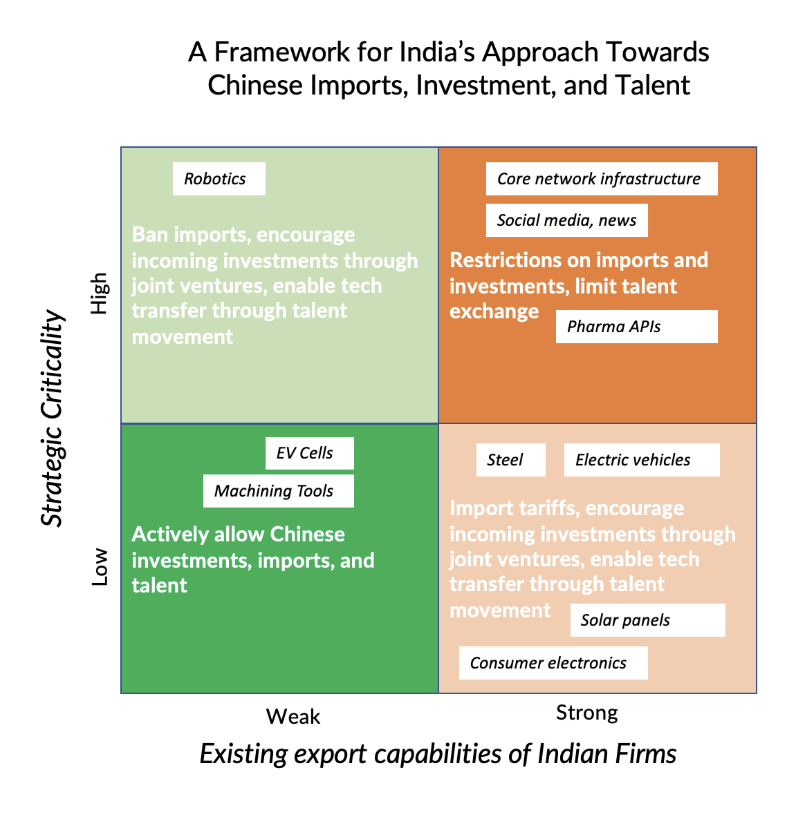

One way to realise the “small yard, high fence” approach is to consider the interaction of two factors:

Strategic criticality of a product or sector: is the product crucial to India’s national security, defence or information space? Are Chinese firms the only suppliers of the product or the only players in the sector?

The existing capacity of Indian firms: Since Chinese firms’ overcapacity is fueled by government subsidies and their governance model can decimate global competition, it becomes necessary to support competitive Indian firms. To measure existing capacity, a demonstration of export potential is a good indicator. Firms in India are protected through various means, and domestic performance can overestimate their competitiveness.

The intersection of these two factors produces four scenarios, as shown in Figure 2.

In tech-heavy sectors where India has weak export capabilities, such as EV cells and machining tools, there is a case for India to allow Chinese investment, imports, and talent actively. On the other hand, if India does have proven export capabilities, there is a case for balancing tariffs with a permissive investment environment.

In tech-heavy sectors with national security implications and little or no Indian export capability, there is a case for attracting investments through joint ventures. Critical sectors with proven Indian export capabilities can continue to limit any exchange with China.

While we argue for a recoupling of Indian and Chinese economies, this should not be taken to mean that Chinese political and military stance towards India will change anytime soon. This is because the CPC does not consider India an equal, and for many decades now, nationalism in China has been directed towards its competition with the US. A closing gap between India and China will likely make China more antagonistic and aggressive towards India.

Nevertheless, China’s competitiveness in manufacturing and its technological innovations were possible because it was willing to harness Western investments despite political and ideological differences. Though the India-China relationship remains complicated due to simmering tensions along their shared border, India must take a leaf out of China’s book and cautiously utilise Chinese products, investments, and talent to close the power gap.

6. Conclusion

China’s rapid rise from being a mass manufacturer of low-quality, cheap products to technological superpower status has surprised much of the world, especially given the popularly held belief that the absence of political liberalisation would hinder innovation.

However, it would be erroneous to linearly draw from China’s growth story over the last thirty years to project its prospects. A close examination reveals that the foundational factors that have been key to the Chinese story no longer apply to the same extent. Since Xi Jinping assumed power, China seems to have jeopardised the sources of its innovation.

China’s rise was made possible by a benign geopolitical environment and supportive international linkages that allowed for a free flow of capital, talent and technological know-how that the country then leveraged through committed capability building, industrial policy, and brutal competition in its private sector.

But in recent times, its domineering ambitions and expansionist posture have shifted the world’s perception of China to that of a strategic rival and threat. Coupled with Chinese products increasingly flooding the global economy, efforts to decouple and derisk from China are genuine, if not coordinated.

This is made worse for China by structural challenges on its domestic front, a one-two punch for Chinese firms. An economy with stalling growth and weak demand, as well as a high unemployment rate and an ageing population, is sure to crunch corporate revenues and flatten government expenditures, dampening their ability to reinvest in R&D, mobilise risk-taking, and sustain technological breakthroughs. Geopolitical difficulties will likely push China to prioritise S&T innovation and continue to dazzle the world in its pursuit of indigenous innovation over this decade. However, the gap with the US that China was rapidly closing in on will likely widen further. China’s recent breakthroughs, then, are embers of a dying fire rather than a juggernaut.

This balanced outlook of China’s S&T future presents opportunities for India. As the world seeks to diversify global supply chains away from China, Chinese firms with weak local consumption will increasingly seek to expand their operations into other countries. Thanks to its lucrative market, India is in an advantageous position and must seize this opportunity.

A key lesson to learn from China’s technology growth story might just be the pragmatism with which China continuously learnt from foreign powers, often setting aside political and ideological differences. This receptive mindset helped China stage a once-in-a-century growth story - in scale, size and impact - upending expectations and stunning the world in the process. India must take a leaf out of China’s book and use China to progress itself. Countering India’s China challenge on the technology front requires more engagement with Chinese firms, not less.

Footnotes

C-SPAN, “User Clip: Clinton on Firewall and Jello”, Mar 8, 2000, (last accessed April 15, 2025)↩︎

“Dancing kings: Unitree humanoid robots, backed by Alibaba tech, delight Spring Gala show”, South China Morning Post, January 29, 2025 ↩︎

“China’s nuclear fusion scientists set record span for plasma 6 times hotter than the sun”, South China Morning Post, January 21, 2025; Bhaswar Kumar, “China’s 6th-Gen Fighter Targets Unmatched Stealth, Claim Chinese Scientists”, Business Standard. January 2, 2025. ↩︎

World Intellectual Property Organization. 2024, “Global Innovation Index 2024 - GII 2024 at a Glance” ↩︎

“Nature Index 2024 Research Leaders: India Follows in China’s Footsteps as Top Ten Changes Again”, Nature Index, June 18, 2024 ↩︎

Kartik Bommakanti (2024). “China’s Military Modernisation: Recent Trends - 2024”. OBSERVER RESEARCH FOUNDATION,, September 24, 2024↩︎

JOE McDONALD and HUIZHONG WU, AP NEWS. “Top Chinese Official Admits Vaccines Have Low Effectiveness,” April 11, 2021 ↩︎

‘Office of Public Affairs | Chinese National Sentenced to Prison for Conspiracy to Steal Trade Secrets | United States Department of Justice’, 5 October 2016. ↩︎

Bharti, Nitin Kumar, and Li Yang. ‘The Making of China and India in the 21st Century: Long-Run Human Capital Accumulation from 1900 to 2020’, 2025.↩︎

Saurabh Todi and Pranay Kotasthane, “China’s Quest for Innovation and Technological Advancement”, The Takshashila Institution, July 2023↩︎

Teng Jing Xuan, “Chinese R&D Spending Continues to Grow, but Regional Inequality Persists - Caixin Global”, Caixinglobal.com, 2019↩︎

Li, Yin. 2022. China’s Drive for the Technology Frontier. Taylor & Francis.↩︎

“End of Year Edition – against All Odds, Global R&D Has Grown close to USD 3 Trillion in 2023”, Global-Innovation-Index, 2023↩︎

Cheung, Tai Ming. Innovate to Dominate. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022.↩︎

“Local Governments Power up to Advance China’s National AI Agenda”, Merics. April 26, 2018 ↩︎

Schell, Orville, and John Delury. Wealth and Power. Hachette UK, 2013.↩︎

Arumí, Javier Borràs.“When China and Japan Were Friends”, April 19, 2022, ↩︎

“China is not crowding out FDI from the rest of East Asia, Experts Say | UNCTAD”, Unctad.org. March 7, 2005↩︎

“Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows (% of GDP) - China | Data”, World Bank↩︎

Chan, Kyle, “How China Uses Foreign Firms to Turbocharge Its Industry”, High Capacity, March 29, 2024; USCC, Kyle Chan Testimony, Feb 6, 2025↩︎

Ibid↩︎

Mu, Qing, and Keun Lee, 2005, “Knowledge Diffusion, Market Segmentation and Technological Catch-Up: The Case of the Telecommunication Industry in China” Research Policy↩︎

Hannas, William C, and Didi Kirsten Tatlow. China’s Quest for Foreign Technology beyond Espionage. London New York Routledge, 2021.↩︎

Wang, Dan. 2023. “China’s Hidden Tech Revolution” Foreign Affairs, February 28, 2023. ↩︎

Jiang, Monika, “Shenzhen: China’s Ecosystem for Open-Source Innovation”, February 8, 2018↩︎

Chan, Kyle, “China’s Faustian Bargain for Foreign Firms”, High Capacity. February 14, 2025↩︎

Dunne, Michael, “China Is Done with Global Carmakers: ’Thanks for Coming’” , The Dunne Insights Newsletter, August 6, 2024↩︎

Stanford University, “Evaluating the Success of China’s ‘Young Thousand Talents’ STEM Recruitment”↩︎

Anna Puglisi, Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 24 February 2023↩︎

Ibid↩︎

Hannas, William C, and Didi Kirsten Tatlow, 2020, China’s Quest for Foreign Technology. Routledge.↩︎

Ibid↩︎

Dychtwald, Zak, “China’s New Innovation Advantage” Harvard Business Review. May 1, 2021↩︎

“China Wasted $6.9 Trillion on Bad Investment Post 2009 - Media”, Reuters, November 20, 2014↩︎

Douglas B. Fuller, Paper Tigers, Hidden Dragons (Oxford University Press, 2016)↩︎

Luong, Ngor, Zachary Arnold, and Ben Murphy. 2021, “Understanding Chinese Government Guidance Funds”,Center for Security and Emerging Technology, March 2021↩︎

Bloomberg News. “China’s Abandoned, Obsolete Electric Cars Are Piling up in Cities”, Bloomberg.com, August 17, 2023; Chen, Caiwei. “China Built Hundreds of AI Data Centers to Catch the AI Boom. Now Many Stand Unused”, MIT Technology Review, March 26, 2025. ↩︎

Hannas, William C, and Didi Kirsten Tatlow, 2020, China’s Quest for Foreign Technology. Routledge.↩︎

Tai Ming Cheung, “Innovate to Dominate”, Cornell University Press, August 30, 2024↩︎

Ibid↩︎

Reuters, “China Sets up Third Fund with $47.5 Bln to Boost Semiconductor Sector”, May 27, 2024↩︎

“China Urges EV Makers to Buy Local Chips as US Clash Deepens”, Bloomberg, March 15, 2024↩︎

Zeyi Yang, “Corruption is sending shockwaves through China’s chipmaking industry”, MIT Technology Review, August 5, 2022↩︎

Kumar Priyadarshi, “14,000+ Chinese Chip Firms Shut down in 2024 amid Industry Turmoil - Techovedas”, Techovedas, December 24, 2024; Ventura, Luca, “China: Chips Fall out - Global Finance Magazine”, Global Finance Magazine, October 4, 2022↩︎

McMorrow, Ryan, and Demetri Sevastopulo, “China’s Tech Minister Removed from Office”, Financial Times, February 28, 2025↩︎

Creemers, Rogier. “The Pivot in Chinese Cyber Governance” China Perspectives 2015, no. 4 (December 1, 2015): 5–13↩︎

Jiang, Jiang, Jia Yuxuan, and Yu Liaojie, “China’s Plan on Reforming Party and State Institutions - Near-Full Translation of Official Document”, Ginger River Review, March 16, 2023 ↩︎

Lant Pritchett, “How Did China Create ‘Directed Improvisation’?”, Building State Capability, 2017, Harvard Kennedy School ↩︎

Hon. Nazak Nikakhtar, “U.S. Businesses Must Navigate Significant Risk of Chinese Government Access to Their Data”, Wiley law, March 2021↩︎

Cary Springfield, “What’s Really behind Beijing’s Crackdown on Its Tech Industry?”, International Banker, March 24, 2022 ↩︎

Robertson, Jordan, and Michael Riley, “The Big Hack: How China Used a Tiny Chip to Infiltrate U.S. Companies”, Bloomberg, Oct 4, 2018 ↩︎

BBC News, “ZTE Fined $1.1bn for Flouting US Sanctions against Iran,” March 7, 2017 ↩︎

Lohr, Steve, “U.S. Moves to Ban Huawei from Government Contracts” The New York Times, August 7, 2019↩︎