Economic and Security Implications of Pakistan’s Cryptocurrency Push

Authors

Executive Summary

Shobhankita Reddy is a Research Analyst with the High-Tech Geopolitics Programme.

Anupam Manur is Professor of Economics at the Takshashila Institution.

This paper finds that Pakistan’s recent push to adopt cryptocurrency is a net negative for its economy and India’s national security if implemented beyond mere announcements and experiments. Given the structural vulnerabilities in Pakistan’s economy, making crypto a legal tender or allocating a portion of the country’s strategic reserves in crypto is only likely to expose the country to new economic risks rather than mitigating existing ones. However, it could benefit from the potential of crypto for evading sanctions, funding cross-border terrorism and emerging as a hub for money laundering.

Further, the findings suggest that Pakistan becoming a thriving crypto hub and the potential takeover of the country’s crypto assets by its Military-Jihadi Complex (MJC) is the worst-case scenario for India’s interests.

The paper concludes that Pakistan’s move to adopt crypto is helping cultivate favour with the Trump administration in the immediate term. India must monitor Pakistan’s domestic developments in crypto integration and respond appropriately if they directly impinge on its interests.

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Anisree Suresh and Anushka Saxena for their valuable feedback and research guidance.

1. Introduction

For years, Pakistan’s stance on cryptocurrency has been mired in contradictions. While Pakistan’s central bank, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), continued to classify digital currencies as illegal, government committees intermittently explored their potential for applications in financial inclusion. At the same time, Pakistani citizens adopted cryptocurrency with great enthusiasm, making the country a thriving hub for its usage.

While data for cryptocurrency adoption varies, it does appear that by 2022, crypto was popular in Pakistan with the country ranking in the top ten in several global adoption indices. Pakistan is currently estimated to have 2 crore users, a number significantly higher than the 4.2 lakh people who invest in the country’s capital markets.1 Separately, Pakistan has an estimated 4 crore operational crypto wallets.2

2025 saw a vital policy shift. After years of operating in a regulatory grey zone, uncertainty and informal adoption, the SBP has, in September 2025, signalled serious intent to legalise digital assets by withdrawing an earlier directive banning financial institutions from dealing in crypto.3 It also announced its plans to launch a central bank-backed digital currency (CBDC). Subject to a parliamentary ratification before November 2025 and a regulatory framework being implemented, Pakistan’s underground crypto economy, estimated to be worth $20-25 billion, would be pulled out of the shadows.4 Until then, the “Virtual Assets Ordinance” that took effect in July has established a licensing framework for sandbox experimentation under regulatory oversight.5 The newly established federal regulator, Pakistan Virtual Asset Regulatory Authority (PVARA), has a mandate to supervise crypto licensing, countermoney laundering, bring about compliance with global standards, and enforce penalties for violations while encouraging shariah-compliant digital assets. It also recently invited global crypto exchanges and service provider firms to apply to operate in the country.6

Pakistan’s push into the crypto domain merits deeper study, especially due to its choice of timing. It comes only a few months after US President Trump’s vocal support for digital assets, with some analysts noting that Pakistan has gained diplomatically by positioning itself as a crypto-hub.7 This development has geopolitical implications with a bearing on India. As Jake Sullivan, former National Security Advisor of the US, said, “And now, in no small part, I think because of Pakistan’s willingness to do business deals with the Trump family, he has thrown the India relationship over the side. That is a strategic harm in its own right.”8 Further, he warned that such moves by the Trump administration would push US allies globally to hedge against the US, thereby undermining its interests. Dealing with Trump’s transactional approach to alliances and international partnerships would require Indian foreign policy to adapt accordingly.

Additionally, Pakistan’s economy suffers from persistent structural weaknesses – low private investment, tepid growth rate and heavy dependence on imported energy, to name a few. These make it highly vulnerable to external shocks. It has been bailed out by the IMF 25 times since 1958, without undertaking meaningful reforms in public governance or debt management.9 Investing massively in crypto is likely to expose the country to new risks rather than addressing existing economic vulnerabilities. The technology’s anonymous and decentralised nature also opens up the possibilities for it being potentially misused and dominated over by Pakistan’s MJC, especially for the purposes of terror financing and money laundering.

This essay seeks to build on the above developments and speculate on the implications that Pakistan’s initiative towards cryptocurrency may have for its domestic economy, broader geopolitics, and India.

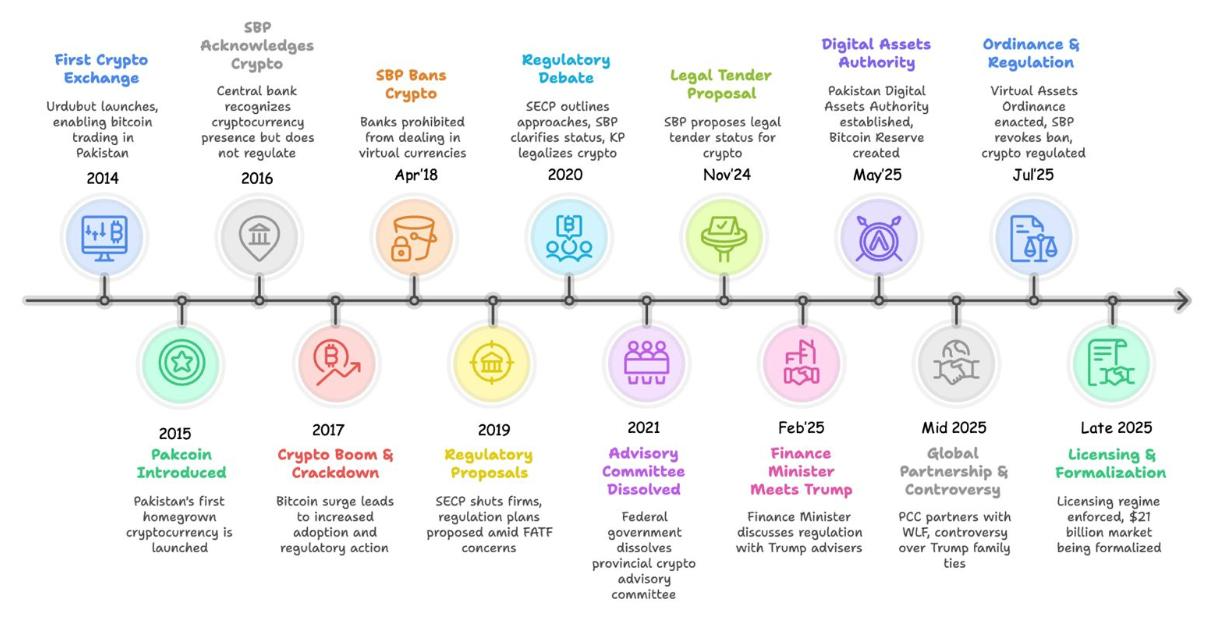

2. Charting Pakistan’s Journey with Cryptocurrency

Pakistan’s engagement with cryptocurrency began in 2014 with Urdubut, the country’s first crypto exchange, which facilitated bitcoin trading. In the next year, the country’s first cryptocurrency called ‘Pakcoin’ was launched. In 2016, the SBP acknowledged the existence of cryptocurrency trading in Pakistan and a lack of public knowledge about it, but did not officially recognise it.10

2017 was a massive bull run for the global crypto market, with the price of bitcoin starting at $900 and ending close to $20,000.11 Crypto adoption soared among the Pakistani citizens and there were efforts by Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) and the SBP to discourage this.12 For instance, crypto companies faced legal action and were referred to as “ponzi schemes”.13 In April 2018, the SBP issued a circular prohibiting banks from dealing in virtual currencies and instructing them to flag any “suspicious” crypto-related transactions to the Financial Monitoring Unit (FMU), reiterating that virtual currencies were not legal tender.14 Several notices were issued to educate the general public of the risks of engaging with these assets, given their speculative nature, price volatilities and lack of stability.15

2019 saw a few signs of regulatory vacillation. On one hand, SBP commended the launch of a blockchain-based, cross-border remittances platform between Pakistan and Malaysia.16 On the other hand, the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) took legal action that led to nine firms dealing in cryptocurrency shutting down.17 There were also plans to introduce regulations on cryptocurrencies as a response to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)’s concerns of their role in terror-financing.18 In a landmark 2020 paper released in guidance with the FATF, the SECP outlined potential approaches to do so and the SBP went back on the 2018 ban and clarified that cryptocurrency was, in fact, not banned – only unregulated.19 It looked like a regulatory framework for the same would be implemented soon. This, however, did not materialise.

In December 2020, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, recognising that crypto was already a booming informal market, and seeking to leverage its economic benefits, unanimously passed a resolution urging the federal government to legalise cryptocurrency.20 Further, it established an advisory committee to explore next steps. It decided to pilot two hydro-powered crypto mining farms and sought to attract investments for the same. However, the federal government continued to maintain a cautious stance, and by 2021, this provincial advisory committee was dissolved.

Between 2020 and 2024, as the price of bitcoin soared past $20,000 globally, the country saw a broad-based adoption of peer-to-peer trading networks, even as cryptocurrency operated in a regulatory grey zone in Pakistan. With a massive youth population – two-thirds of the population in Pakistan is under the age of 30 – that is inclined to be tech-savvy, Pakistan had already become one of the most active global hubs in terms of the size of the crypto user base by 2022. Pakistan is also consistently ranked among the top five remittance-receiving countries in the world, both in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the GDP ( ~8-10%), making payments via digital wallets, bypassing traditional banking services, lucrative for its citizens.21

Finally, after years of deliberation on crypto regulation, on November 4, 2024, only a day before the US presidential elections, the SBC unveiled a set of policy proposals that, if approved, would give cryptocurrencies the status of legal tender in the country.22 The timing carried geopolitical weight, given the backdrop of Trump’s pro-crypto rhetoric on his campaign trail.

Since taking office, Trump has signed two important executive orders concerning digital assets. Together, they established the US Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and Digital Asset Stockpile composed of forfeited bitcoin and other digital assets held by the government, designating them as US reserve assets that are not to be sold to the private sector. Trump has also initiated efforts to scale back government oversight of the crypto industry, as seen by the SEC’s dismissal of or pause on several enforcement actions against crypto-trading companies.23 The order also directed agencies to develop a new federal framework for digital assets rather than treating them as identical to stocks and bonds.

The crypto crash began in May 2022 with Terra stable coin and the token Luna, which together wiped out about $45 billion in value in one week. This was followed by the collapse of major crypto platforms, culminating in the collapse of FTX exchange. The price of Bitcoin and Ethereum fell by 65% and 70% respectively during this period.

Trump’s approach starkly contrasts with the Biden administration’s increased scrutiny of large crypto firms, particularly after the collapse of the crypto industry in 2022, the most marked event of which was the bankruptcy of the crypto exchange firm, FTX. Both Donald and Melania Trump have also launched their own cryptocurrency meme coins, with Trump hosting a controversial, exclusive dinner for the top sponsors of his $TRUMP coin in May 2025.24 Further, the administration has passed a law called the Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins (GENIUS) Act to create a regulatory framework for dollar-pegged stablecoins.25 However, in a move purported to protect the sovereignty of the US dollar, Trump’s executive orders explicitly prohibited federal agencies from developing, issuing or promoting CBDCs, curtailing their role in online payments. CBDCs are central-bank-issued and controlled digital versions of the country’s fiat currency, while stablecoins are tokens issued on crypto blockchains by private players that are nominally pegged to a fiat currency. By banning the use of CBDCs and endorsing stablecoins, Trump’s move is a curious case of support for private-player domination of the digital currency landscape at the risk of restricting the role of the government.

Pakistan’s permissive stance on crypto has conspicuously aligned in timelines to Trump’s support of the ecosystem. In February 2025, Pakistan’s Finance Minister met with a foreign delegation of Trump’s advisers to discuss crypto regulation. Subsequently, the government established the Pakistan Crypto Council (PCC), which, in May, was upgraded to a full regulatory body called the Pakistan Digital Assets Authority (PDAA) with a mandate to regulate, license and oversee the digital assets ecosystem in the country. Bilal Bin Saqib, Pakistan’s Minister of State for Blockchain and Crypto and Head of PCC, has publicly acknowledged Trump’s role in Pakistan’s push for crypto when he announced the creation of a Strategic Reserve exclusively focused on Bitcoin.26 This is meant to be a sovereign asset with a long-term holding commitment, not for speculative trading or sale. The PDAA has allocated 2000 megawatts of electricity to support mining operations and data centres.27 The Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC), a federal body with the primary goal of coordinating between government departments and fast-tracking FDI into the country, has recently issued a license for Pakistan’s first high-performance computing data centre for bitcoin mining, which is a shift from its past mandate for IT and digital technology-related investments.

The PCC announced a partnership with the World Liberty Financial (WLF), a decentralised finance venture that launched a dollar-pegged cryptocurrency called USD1. While the full details of the deal are unclear, it was reported that WLF would provide strategic guidance and help develop Pakistan’s digital infrastructure, support blockchain technology innovation, expand stablecoin adoption for trade and remittances, and tokenise assets like real estate to enable integration of the technology in Pakistan’s economy.28 This deal attracted global criticism and media attention due to WLF’s significant connections to the Trump family, who hold a 60% stake in the company. Notably, WLF’s co-founder is the son of Trump’s long-time friend and real-estate associate, Steve Witkoff, who is also US Special Envoy to the Middle East, a trusted position that during Trump 1.0 was held by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner.

Even as the PCC drew worldwide scrutiny, the federal government and central bank in Pakistan continued to reiterate that the use of cryptocurrency was illegal and would be liable to be investigated by the FMU and the FIA.29 This changed with the promulgation of the Virtual Assets Ordinance in July 2025 – the first formal law to legalise, regulate and license digital tokens and blockchain-based assets – and the SBP revoking the 2018 directive.30 Currently, virtual assets are not legal tender in Pakistan, with the ordinance explicitly stating that they can be transferable within a prescribed digital ecosystem, but not for the general purchase of goods and services.

Among the key provisions of the ordinance is the establishment of an extensive licensing regime. Virtual asset issuers and service providers must obtain the approval of PVARA, meet strict compliance requirements of anti-money laundering and counterterrorism financing rules (AML/ CTF), and submit extensive documentation regarding their business model operations, fitting them to the requirements of the Pakistani market. As some analysts have noted, the licensing framework could help bring a large crypto market currently operating in an informal landscape under regulatory purview, and expedite the formalisation of the sector.31 They contend that this would protect consumers from fraud and support the state’s efforts to monitor illicit transactions, while aligning the domestic innovation ecosystem with global standards. However, the MJC network in Pakistan and the significant influence it commands on power structures in the country, as well as the fragile state of the country’s economy, raise serious questions about the effective implementation of this framework.

Having traced Pakistan’s journey with cryptocurrency, the next section explores some concerns.

3. Implications for Pakistan

Pakistan has several deep-seated economic challenges that make cryptocurrency adoption lucrative for its population. This section lays them out and then discusses the implications that the push towards crypto may have for its economy.

3.1 The State of Pakistan’s Economy

Pakistan’s economy suffers from persistent structural weaknesses. A narrow tax base with only ~2.5% of the population filing taxes in FY24 and a tax-to-GDP ratio of 10.5% in 2023, low economic productivity and low foreign investment, heavy dependence on imported energy, a bloated public sector and the lack of institutional processes or transparency have entangled the country in chronic fiscal mismanagement.32 With unstable inflation rates, plummeting foreign reserves, and a depreciating currency against the dollar, the government has institutionalised import restrictions and fiscal austerity to combat a balance of payments crisis that is always around the corner.

This has made local industries less competitive internationally. The production of export commodities is heavily linked to the import of necessary input materials. Rising import bills alongside a Pakistan rupee falling against that of its trading partners makes production very expensive. The country’s textile industry, its largest manufacturing sector, is a case in point. Structural decline in labour productivity, lack of modernisation and rising input costs, have resulted in Pakistan lagging behind regional competitors such as Bangladesh and Vietnam. Pakistan’s export base as a percentage of its GDP has declined the past two decades and stood at 10% in FY21, while the country runs a trade deficit, contributing to a growing current account deficit.33

One-fourth of Pakistan’s imports is oil and gas. Here too, the country’s energy sector is plagued by inefficiencies. The 1994 Independent Power Producers (IPPs) Policy that invited foreign investors into the power sector essentially guaranteed them profits pegged to the US dollar, transferring the risk burden entirely to the Pakistani state and taxpayer. The energy reforms in the 1990s, also an IMF conditionality, prioritised imported furnace-oil-based power generation. This increased imports of oil and gas, while making electricity production more expensive - the per unit cost of electricity from these fuels is eight times more than that of electricity produced from water. These IPPs contribute to around half the power produced in Pakistan and rely on government subsidies for their operations.34 Rising fuel prices, dollar fluctuations and a flailing economy have hampered the government’s ability to make these payments, exposing the country to frequent power outages. These practical hurdles cast doubts on the Pakistan government’s ambitious plans for crypto mining, making it almost unfeasible.

Pakistan also has poor socioeconomic indicators. In the 2024 Global Hunger Index, Pakistan ranked 109th out of 127 countries.35 According to the World Bank for FY24, Pakistan had a 40.5 per cent poverty rate, defined as the percentage of the population living for under $3.65 per day in PPP terms.36 Public expenditure on health and education is below 3 per cent of the GDP, and by mid-2023, Pakistan had become the fifth largest country for illegal immigration to Europe.37

Compared to the economic crisis between 2022 and 2024, Pakistan’s economy has now stabilized in 2025. May 2023 saw a record high inflation rate at 38 per cent, the highest since 1957 for the Indian subcontinent.38 Foreign reserves, too, dropped drastically to just two weeks of imports during the same period. The latest infusion of capital from the IMF in September 2024 - a $1 billion disbursement of a $7 billion approved package, bilateral bailouts, import restrictions and tighter monetary policies have helped. Pakistan posted a current account surplus of $2.1 billion in fiscal year 2025 - its first in fourteen years.39 However, as many analysts have noted, this is a statistical artefact that has been made possible by remittances and import curbs, and not structural changes via reforms, investment growth or export-led expansion.40 While the country continues to suffer from weak credit access in the international bond markets, repayments worth $23 billion are due this fiscal year, and annual debt rollovers from China, Saudi Arabia and the UAE would be key to avert another balance of payments crisis.41

Given the state of the Pakistani economy, widespread use of crypto among its citizenry, as a way to gain access to the US dollar, park savings in crypto even as it is a non-productive asset class for the country’s economy, and hedge against high inflationary periods, is understandable.

3.2 Implications for Pakistan’s Economy

Pakistan has formally announced the inclusion of bitcoin in its strategic reserve, but the status of stablecoins and CBDCs is still entirely unclear as of this writing. They seem to be experimental, limited to pilot programmes, and part of a phased programme for a broader digital adoption.42 Having laid out the vulnerabilities in the Pakistani economy, this section will list the implications crypto adoption may have.

A Strategic Reserve is a broad concept to denote the holding and stockpiling of important assets for emergency and contingency purposes. Strategic reserves can be of any important asset, such as oil, medicine, and financial assets. Forex reserves, on the other hand, is a subset which denotes the buildup of foreign exchange (other countries’ currencies, gold and SDRs) through trade surpluses and is held to buffer against temporary balance of payments deficits.Since Cryptocurrencies cannot be used for trade purposes and does not feature under the balance of payments yet and is not held by the central bank, it will be deemed as a strategic reserve and not a forex reserve.

3.2.1 Reserves as Import Buffer

While the IMF now tracks bitcoin, stablecoins and other digital assets in its cross-border finance stats, a formal framework granting them the status of legal currency or establishing their holdings by central banks as strategic reserves, the same way gold, foreign currencies or sovereign bonds are, is missing.43 Reserves are meant to provide a financial safety net against external vulnerabilities and crises such as currency depreciation, increased capital outflows or a drop in exports and help with the continued ability to import essential commodities. The historical volatility in cryptocurrency prices, including in stablecoins despite what the name might suggest, with drawdowns as high as 50-80%, makes the asset largely incompatible with the stability mandate of foreign exchange reserves. Currently, the acknowledgement of cryptocurrency’s increasing role in global finance seems limited to tracking and monitoring it for increased transparency.

El Salvador was the first country to accept bitcoin as legal tender in 2021, and the country’s tryst with crypto is worth studying. About $60-75 million of the country’s holdings disappeared during the crypto bear market run of 2022-23. While this has now recovered and the country, in fact, benefitted from buying the dip when the crypto market was down, crypto’s high volatility and speculative nature keep the fiscal risk intact. Additionally, El Salvador has needed the IMF’s financial support multiple times in its recent history, and the IMF has required, as part of a $1.4 billion bailout in February 2025, that the country scale back its bitcoin accumulation.44 Despite this, the government has cautiously adjusted by distributing its holdings into multiple wallets to prevent security risk. It is also moving to abolish its status as a legal tender by making bitcoin payments voluntary and not mandatory, and limiting its participation to the private sector. For example, taxes can no longer be paid in bitcoin, and the state-controlled wallet, Chivo, that heavily promoted bitcoin transactions, is being disbanded.45

While the US Strategic Reserve in Bitcoin has garnered global attention, the regulatory framework for crypto in international finance is evolving. Crypto is unlikely to be able to play the role of an import buffer in the near future, compounding the risk for Pakistan’s economy. Maybe a worthy question to ponder is what percentage of strategic reserves in this asset class would be considered safe from a portfolio diversification perspective, while being considered safe from price crashes.

3.2.2 Sanctions Evasion

Cryptocurrency’s borderless and pseudonymous nature has the potential to evade US and EU sanctions. Iran’s case is instructive in this regard. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a branch of Iran’s military, has used cryptocurrency to evade sanctions, fundraise, and conduct covert operations.46

Iran’s approach to cryptocurrency is one of heavy oversight. The Central Bank of Iran is the sole authority that regulates, licenses, and oversees crypto exchange operations. While licensed crypto mining is legal, the mined cryptocurrencies must mandatorily be sold to the government to fund imports. Illegal mining and compliance deviances are monitored strictly using a centralised architecture for regulatory control and surveillance.

A recent regulation has shut down cryptocurrency exchange payment gateways in the country. While there are reports of a cross-border gold-based stablecoin being deployed with Russia and over $3 billion in crypto transactions in 2022, this move seems to be aimed at controlling the damage to businesses from power outages in an already fragile energy infrastructure.47 Additionally, the dramatic depreciation of the Iranian rial against the US dollar, hitting a record high of a million rials for a single dollar in April 2025, has had civilians flock to these exchanges as an inflationary hedge. The move to shut Rial-crypto exchanges would curtail civilian access to alternative financial instruments, increase state supervision of the currency market and the digital asset landscape, and prevent capital flight.

While Pakistan’s financial constraints and scrutiny by the FATF make crypto an attractive option, the lack of tight oversight and institutional processes risks an economic disaster. Although the current licensing regime tends towards centralising control, Pakistan’s weak institutional capabilities make implementation difficult and could exacerbate financial instability, exposing the country to macroeconomic challenges.

3.2.3 Macroeconomic Implications

With a surge in cryptocurrency adoption in Pakistan, there will likely be a number of macroeconomic implications for the economy. If crypto is indeed accepted as legal tender, to begin with, there would be currency substitution to dollar-based stable coins, which could lead to a de-facto dollarisation of the economy. Residents would hold and transact in crypto than Pakistani Rupee (PKR), reducing demand for rupee money balances and eroding seigniorage. This would depreciate the PKR further, which would make imports costlier, leading to higher inflation in the economy. This has significant equity implications within Pakistan, as one section of society will be stuck using a depreciated PKR and paying for costly imports, while another section of the population can ride the crypto wave.

Even if it is not legal tender, but accepted only for investment purposes, it could weaken Pakistan Central Bank’s monetary policy transmission coefficient. If savings migrate from PKR deposits to crypto wallets or offshore exchanges, the funding costs for banks to lend money would rise and the credit channel weakens, reducing interest‑rate transmission. Thus, credit availability for industry would be hampered as well.

Finally, a widespread use of crypto could severely weaken the State’s ability to collect tax revenue from its citizens, which could further weaken provision of public goods, strong governance, maintaining law and order, and welfare expenditure. All of these could further destabilise Pakistani society.

4. Implications for India

This section focuses on the implications Pakistan’s recent move may have for India’s interests, both geopolitically and in terms of its national security.

4.1 Cultivating favour with the Trump Administration

The previous sections established the Trump angle in Pakistan’s embrace of cryptocurrency. In this light, Pakistan’s overtures to cryptocurrency appear to be an opportunistic gamble aimed at wooing the Trump administration by appealing directly to his family’s business interests.

This is also exemplified in Pakistan’s promises of expanding on critical mineral exploration and mining to serve US interests. Among the first signs of this came in April 2025 when a US delegation travelled to the Pakistan Minerals Investment Forum seeking to expand opportunities for American businesses in Pakistan.48 It recently took a dramatic turn when Army Chief Asim Munir and Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif displayed glimpses of the country’s purported rare earth deposits to Trump.49 Subsequently, the American firm, US Strategic Metals, signed a $500 million mineral deal with Pakistan.50

One outcome of this outreach is that Trump seems to have a more favourable stance towards Pakistan in his second term – a marked deviation from US-Pakistan relations in recent years.

Trump’s first term was a tumultuous time for US-Pakistan ties. Between 2016 and 2018, the US’s concerns were almost singularly focused on Pakistani safe havens for militant and terrorist groups. This reached a crescendo when Trump publicly accused Pakistan of “lies and deceit” and cut off $1.3 billion in security assistance.51 This dynamic shifted in the latter half of his presidency as Pakistan became a key player in the negotiations with the Taliban and the US prepared to withdraw its troops from Afghanistan. Further, as Pakistan continued to remain important in the intra-Afghan peace talks later on, the US-Pakistan relationship saw goodwill measures in the fight against COVID.

Comparing this with Trump’s second term so far, there are several reasons to believe that US-Pakistan ties have improved. Trump has repeatedly praised Pakistan’s role in counterterrorism, and several high-profile exchanges have been held between the two sides. In sharp contrast to Pakistan’s security assistance being cut off in the previous term, this time around, Islamabad was explicitly exempted from Washington’s foreign aid cuts in February of 2025. A similar posture was adopted in the latest visa restrictions policy, where Pakistan does not find a mention in the list of 12 countries whose nationals are restricted due to national security concerns.52

In May, Trump claimed to have brokered the India-Pakistan ceasefire in the military escalations post the attack in Pehelgam. While India rejected this claim, Pakistan responded by nominating Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize and lauding his intervention. The White House lunch with Field Marshal Asim Munir in June immediately after is noteworthy - the first time in 15 years that a sitting US president hosted a Pakistani military chief.53

The Pakistan-US trade deal brokered in July 2025 offers lower tariffs for Pakistani exports in exchange for investments to develop Pakistan’s oil reserves in Balochistan, Sindh, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Other aspects of this deal include cooperation in IT, mining, cryptocurrency and digital infrastructure. The 19% tariff on Pakistan is the lowest of any nation in the Indian subcontinent, a powerful symbol of Pakistan’s improving economic, strategic and diplomatic ties with the US. Additionally, the US military has been partnering with Pakistan for counterterrorism operations and joint military exercises.

In contrast, a visible departure from the previous US policy on India has put US-India ties under strain. What started as 25% tariffs on India escalated to 50%, with Trump citing India’s continued purchase of discounted Russian oil as the reason for the “penalty”. Compared to the Pakistan response, India’s rejection of the US’s third-party mediation in what it sees as a bilateral issue has complicated the dynamic.

These serve Pakistan’s interests while undermining that of India. A potential shift in US policy rehyphenating India-Pakistan and legitimising Pakistan’s military establishment would also have implications for the security dynamics of the Indian subcontinent.

It is important to note that Trump’s transactional diplomacy creates considerable uncertainty about the long-term stability of US-Pakistan ties. Currently, the relationship seems to be driven more by short-term economic opportunities rather than a structural strategic alignment.

However, for now, it does appear that Pakistan has managed to position itself well with multiple countries at once. Apart from the US, the two other powers that Pakistan seeks to balance are Saudi Arabia - a country with which it recently signed a defence pact - and China, with which it has a deepening economic, military and diplomatic ties, such as a $62 billion investment under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Although questions remain on Pakistan’s ability to deliver on its commitments to each partner, India must watch these developments carefully lest they have the potential to tip the regional balance of power away from India.

4.2 Combatting Cross-Border Terrorism

There is increasing evidence of terror organisations like Hamas, Hezbollah and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) using cryptocurrency for fundraising, circumventing governmental detection and counter-terror financing measures.54 Complex networks involving multiple wallets, exchanges and intermediaries on privacy-oriented cryptocurrencies that are designed to obscure transaction details are used to gain anonymity and evade intelligence agencies. The FATF has repeatedly warned about the emerging risks of terror financing using digital assets.55 It has issued global, binding standards that Virtual Asset Service Providers must follow to prevent their misuse.56 In Pakistan, too, there is evidence of ISIS-linked terrorists using cryptocurrency to make payments.57

In fact, the conceptualisation of Pakistan as two distinct but overlapping components - a putative state represented by the civilian government and the MJC, the entity controlling the power structures, is important to highlight that the military establishment in Pakistan is not merely a supporter of its jihadi outfits but is structurally coupled with them.58

In this framing, the Pakistani state’s support for crypto puts much at stake for India’s efforts to counter subconventional warfare from across the border. The current licensing framework for cryptocurrencies in Pakistan raises significant concerns about the potential for market capture and crypto asset takeover by the country’s MJC. For example, it has been reported that the SFIC, a federal regulatory body nominally a part of the civilian administration in Pakistan, has 36 serving military officers, raising questions about genuine parliamentary oversight of its decision-making.59

The MJC already wields extensive control over several sectors in Pakistan, like energy and real estate. It often runs, regulates, and profits from these through a network of military-owned businesses, such as the Fauji Foundation and Army Welfare Trust. The PDAA, then, is likely to operate not like a civilian body but more akin to a crypto division of the MJC.

The MJC being functionally intertwined with anti-India outfits makes cross-border terrorism funding against India a pressing threat. Further, could a time come when a part of the defence budget in Pakistan is funded by the country’s digital assets?

4.3 Money Laundering

Unchecked, widespread adoption of cryptocurrency in Pakistan risks positioning the country as a hub for illegal financial activities like money laundering, arms dealing, drug trafficking, etc. While no legal crypto exchanges exist between India and Pakistan currently, cross-border transactions between the two countries are among the most surveilled in the world, making crypto an attractive option to skirt oversight, even though there exists regulation in India. The comparison to the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) in the 1980s may be effective. Founded by a Pakistani banker, the bank was notorious for facilitating illegal trade through its global network of shell companies before its eventual, infamous collapse.

Cryptocurrencies are not recognised as legal tender in India, which means that it cannot be used to make payments for goods and services. It is recognised as a Virtual Digital Asset and they are legal to hold, trade, and invest in with specific restrictions and compliance obligations. It is also taxed at a flat rate of 30%.

Cryptocurrency has the potential to play the role of a modern-day BCCI today, evading governmental financial compliance requirements and attracting illicit actors from India and beyond. While coordinated global and institutional oversight remains nascent, sophisticated techniques to break transaction trails, such as cross-chain transfers, privacy coins and mixers exploiting governance gaps in supervision, could pose a serious threat to global finance, and also to India’s national interests.

Pakistan already has a thriving hawala system owing to the country’s limited financial inclusion and people’s distrust in its formal banking system.60 Several arrests have uncovered cases linked to money laundering and terror financing using these networks.61 E-hawala, or blockchain-enabled hawala, would add an additional layer of complexity in flagging such transactions.

If Pakistan does allow itself to be a laundering haven, it risks re-entry to the FATF grey list, which it exited only in 2022. This would bring with it increased scrutiny, further complicating foreign investment into the country. However, partly owing to the country’s improved relations with the US and the pseudonymous nature of blockchain technology, establishing a convincing case for this to enforce global action may prove to be difficult for concerned economies like India.

4.4 Pressure on India to legitimise Crypto

A thriving global cryptocurrency market, particularly in major regional economies like the UAE, Pakistan, and Singapore, alongside its existence in giant markets like that of the US, could significantly impact India. Easy access to these markets for Indian citizens might lead to cross-border capital outflow, weakening India’s foreign exchange controls, tax collection, and formal banking channels, and causing other macroeconomic disruptions.

These pressures may compel the Indian government to re-evaluate its stance on cryptocurrency and establish a formal regulatory framework, potentially opening up markets for crypto exchanges. This shift in policy might be driven by the need to curb illicit capital outflow rather than a proactive measure taken in the interest of the Indian economy.

5. Scenario-Based Analysis

Cryptocurrency and related assets hold much promise for financial inclusion, spurring digital innovation and experimenting with novel business models. Yet, a phased implementation model delineating product use cases, along with comprehensive risk management and alignment with global standards, would be prudent. Pakistan’s desperate push to adopt crypto brings this into question. Drawing from the previous sections, four scenarios may be possible as to how this may play out. These scenarios are illustrative and not exhaustive, and have been arranged in order of decreasing probability of occurrence and implementation difficulty for Pakistan.

5.1 Scenario 1 - All talk, no action

As evident from Pakistan’s grandiose plans for crypto mining when the country, in reality, suffers from severe power outages, Pakistan’s urgent push to adopt crypto is likely meant only to appease the Trump administration, with ground implementation happening at a much slower pace or not at all. The pace of crypto growth in the country will be maintained and the number of crypto accounts will grow, but will be used largely as a store of value.

This is the best-case scenario for Pakistan and one that is currently playing out during the country’s transitional phase prior to the Virtual Assets bill being ratified by the parliament. This would help Pakistan improve its ties with the US while averting any negative economic consequences from crypto adoption. The opportunistic nature of this move has short-term geopolitical implications that India must watch out for. From an economic security perspective, not having a thriving crypto hub in the neighbourhood favours India.

5.2 Scenario 2 - Pakistan legalises and allocates a small chunk of its strategic reserves in crypto without declaring it legal tender

In this scenario, trading in crypto could be legal and open to all individuals and businesses. Though it is recognised as an investment class, regulations around trading in crypto are either non-existent or weak. Pakistan’s central bank may hold crypto assets as part of its strategic reserves, per its stated intentions. Simultaneously, the pace of growth of crypto wallets and accounts may increase and people may shift to holding crypto assets for savings and investments, instead of PKR-denominated assets.

Bad fiscal and monetary policies on the domestic front, with currency depreciation or high inflation, would expose Pakistan’s economy to capital flight, worsening the country’s economic situation and causing financial instability. This would heighten the risk of terror acts and military escalation against India, as a way for the MJC to build legitimacy, drive nationalistic narratives and garner domestic support.

5.3 Scenario 3 - Pakistan allocates a significant chunk of its strategic reserves in crypto, and it is declared legal tender

In this scenario, the central bank may hold a significant chunk of its strategic reserves in crypto currency, replacing US treasury bonds and other traditional monetary instruments. Simultaneously, select crypto stablecoins may be declared as a legal tender for payments and be integrated into financial systems. Public services may accept crypto for payments and businesses may transact in crypto or PKR.

This would expose the country disproportionately to crypto market shocks and price volatilities. Given that crypto is currently not acknowledged as an import buffer, an external shock coinciding with a major debt repayment deadline or a balance-of-payments crisis is a perfect storm of overlapping crises that would be debilitating for the Pakistani economy. Further, in a situation with two legal tender currencies, the preference will be disproportionately towards the more stable currency. This can lead to capital flight. Given the risk to the PKR, this situation is quite unlikely. The risks from fiscal mismanagement and for India’s security detailed in the previous scenario apply here, too, further worsening India-Pakistan relations.

5.4 Scenario 4 - Pakistan becomes a thriving cryptohub in the region

Cryptocurrencies may form a significant proportion of the strategic reserves held by the central bank. Further, this scenario assumes everything goes according to Pakistan’s announced plans, alongside crypto being recognised as legal tender, the rollout of CBDC and stablecoin and a flourishing user base.

Pakistan positioning itself as a cryptohub, while risking the country’s economy, would make the country a haven for money laundering and terror financing against India. This would complicate cross-border monitoring for Indian intelligence agencies and increase the threat to India’s national security. The risk of sanction evasion, FATF greylisting and MJC takeover of crypto assets would also be the highest in this scenario.

This is the worst-case scenario for Pakistan’s economy and India’s national security. Fortunately, the heavy integration of crypto into the economy that this scenario necessitates means that it is a long time away and very unlikely.

6. Conclusion

As demonstrated by the above mentioned scenarios, any serious cryptocurrency adoption by Pakistan, beyond loud announcements and sandbox experiments, is a net negative for both its economy and India’s national security. Crypto is only likely to expose Pakistan to more economic risks without solving for existing ones. Additionally, crypto integration into the economy is complex and would require extensive state capacity to build compatibility with current financial systems within a strong regulatory framework. Pakistan’s weak institutional strength leaves much to be desired on this front.

It is likely that Pakistan’s crypto adoption is a temporary flirtation aimed at gaining lobbying power and improving ties with the Trump administration, with no ability or intent to follow through. As evidenced by the IMF’s recent rejection of Pakistan’s proposal to subsidise power for bitcoin mining, the country is unlikely to be able to garner much needed international institutional support for these experiments.62 While averting exposure to deep-seated vulnerabilities in the long term, this would help Pakistan with economic relief and geopolitical leverage in the short term. Even if it serves Pakistan’s immediate interests,it remains a pressing concern for India.

India must closely monitor Pakistan’s domestic developments in the crypto domain and especially respond appropriately if crypto integration in the Pakistani economy directly impinges on its interests.

Footnotes

Khan, H. A. (2025, March 28). Pakistan among top countries for crypto adoption with 20 million users — adviser. Arab News; Chakraborty, D. (2025, May 28). Why is Pakistan going all out on crypto? There’s a Donald Trump angle. ThePrint.↩︎

Gain, E. (2025, May 29). Pakistan follows in US’ footsteps, to set up Strategic Bitcoin Reserve: All you need to know. Mint.↩︎

Amin, T. (2025, September 3). SBP agrees, in principle, to legalise digital currencies. Brecorder.↩︎

Ahmed, S. (2025, September 3). SBP prepares to introduce digital currency as legal tender. SAMAA TV.↩︎

The Gazette of Pakistan (2025, July), Ordinance no. VII of 2025.↩︎

Mehmood, K. (2025, September 24). Crypto goes legit in Pakistan as govt rolls out licences. The Express Tribune.↩︎

How Pakistan won over the US leadership after years of isolation. (n.d.). Lowy Institute.↩︎

TOI World Desk. (2025b, September 2). “Threw India ties aside for Pakistan business”: Ex-US NSA Jake Sullivan blasts Trump; calls it a “huge strategic harm”. The Times of India.↩︎

Inamdar, N. (2025, May 14). India-Pakistan conflict: Why Delhi could not stop IMF bailout to Islamabad.↩︎

Hassan Sial, M., & Arif Saeed, M. (n.d.). Issues of Legislation of Cryptocurrency in Pakistan: An Analysis. Annals of Social Sciences and Perspective.↩︎

Higgins, S. (2021, September 13). From $900 to $20,000: Bitcoin’s historic 2017 price run revisited. CoinDesk.↩︎

Cryptocurrency ownership Pakistan 2022. (n.d.). Triple-A – Triple-A.↩︎

Hameed, T. (2017, August 26). FIA takes action against OneCoin and Bitcoin. TechJuice.↩︎

BPRD Circular No. 03 of 2018. State Bank of Pakistan.↩︎

Public Notice CAUTION REGARDING RISKS OF VIRTUAL CURRENCIES. (n.d.). State Bank of Pakistan.↩︎

Peyton, A. (2019). Alipay powers Pakistan’s “first” blockchain-based cross-border remittance service. Fintechfutures.com.↩︎

Merchant, Z. (2019, April 1). Pakistan shuts down nine firms dealing in cryptocurrency. MEDIANAMA.↩︎

Suberg, W. (2019, April 1). Pakistan plans new digital currency regulations following FAFTA’s urging. Cointelegraph.↩︎

Freeman Law. (2023, December 15). Pakistan and Cryptocurrency | Blockchain and cryptocurrency regulations.↩︎

Partz, H. (2021, March 18). Pakistani province to pilot crypto mining farms. Cointelegraph.↩︎

(2025, June 26). Top 10 Remittance-Receiving countries in the World 2025. Tech Remit.↩︎

Greene, T. (2024, November 4). Pakistan moves to regulate cryptocurrency, CBDCs as legal tender. Cointelegraph.↩︎

Nicolle, E. (n.d.). SEC‘s “Demolition” of Crypto Enforcement Met With Cheers as Well as Jeers. Bloomberg.↩︎

Robins-Early, N. (2025, May 13). Top buyers of Trump-sponsored crypto win exclusive dinner with president. The Guardian.↩︎

Lang, H. (2025, July 18). Trump signs stablecoin law as crypto industry aims for mainstream adoption. Reuters.↩︎

FP News Desk. (2025, May 29). Pakistan does crypto somersault to woo Trump, launches first govt-led strategic bitcoin reserve. Firstpost.↩︎

PTI. (2025, May 26). Pakistan allocates 2,000 MW to bitcoin mining and AI data centres. Business Standard.↩︎

Tahir Sherani. (2025, April 26). Trump-backed crypto venture partners with Pakistan Crypto Council to boost blockchain adoption. Dawn.↩︎

Rana, S. (2025, May 30). Crypto currencies use is illegal National Assembly told. The Express Tribune.↩︎

The Gazette of Pakistan (2025, July), Ordinance no. VII of 2025.↩︎

Chakraborty, D. (2025c, September 6). Pakistan’s $21 billion crypto market is out of the shadows. It’s finally legal there. ThePrint.↩︎

Revenue Statistics in Asia and the Pacific 2025. (2025). In Revenue statistics in Asia and the Pacific.↩︎

Mustafa, G., & Hussain, S. (2023, March 28). What Are The Factors Making Pakistan’s Exports Stagnant? Insight From Literature Review. Pide.org.pk; Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, PIDE Islamabad.↩︎

Ariana. (2025, October 2). How the International Monetary Fund Is Squeezing Pakistan. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.↩︎

Index, G. H. (2025, October 8). Pakistan. Global Hunger Index (GHI) - Peer-reviewed Annual Publication Designed to Comprehensively Measure and Track Hunger at the Global, Regional, and Country Levels.↩︎

Pakistan Poverty and Equity Brief : October 2024. World Bank.↩︎

Pakistan Education spending, percent of GDP - data, chart | TheGlobalEconomy.com. (n.d.); Administrator, W. (2023, July 31). Pakistani nationals on the move to Europe: new pressures, risks, opportunities. Mixed Migration Centre.↩︎

ANI (2023, June 2). Pakistan’s inflation rate reaches record high of 38 pc in May. ThePrint.↩︎

Iqbal, S. (2025, July 19). First current account surplus in 14 years. Dawn.↩︎

Editorial. (2025, July 19). Beyond the surplus. Dawn.↩︎

PTI. (2025, July 18). Pakistan faces $23 billion in external debt servicing this fiscal year. The Economic Times.↩︎

Reuters. (2025, July 9). SBP to launch pilot for digital currency, says governor. Dawn.↩︎

CRYPTO: IMF now officially tracks Bitcoin in cross-border finance. (2025, March 25). IFC Review.↩︎

IMF Executive Board Approves New 40-month US.4 billion Extended Fund Facility Arrangement for El Salvador. (2025, February 26). IMF.↩︎

AFP - Agence France Presse. (2024, December 19). El Salvador plans to sell or shut its crypto wallet. Barrons.↩︎

Team, C. (2025, September 16). OFAC targets $600 million Iranian shadow banking network using cryptocurrency to evade sanctions. Chainalysis.↩︎

Boltuc, S. (2025, May 12). Crypto Under Control: The news Geopolitical drivers of Iran. SpecialEurasia.↩︎

Senior Bureau official Meyer’s travel to Pakistan - United States Department of State. (2025, April 5). United States Department of State.↩︎

Rajghatta, C. (2025, September 28). Pakistan plays “Trump card”, flashes mineral wealth in the White House. The Times of India.↩︎

Gilmore, M. (2025, September 11). US Metals Company and Pakistan forge $500 million mineral investment pact. Manufacturing Today.↩︎

Diaz, D. (2018). Trump’s first 2018 tweet: Pakistan has “given us nothing but lies & deceit”. CNN.↩︎

The White House. (2025, June 4). Restricting The Entry of Foreign Nationals to Protect the United States from Foreign Terrorists and Other National Security and Public Safety Threats.↩︎

Dayal, P. (2025, October 3). Can US-PAK honeymoon last?. Times of India Voices.↩︎

Terrorist Financing: Hamas and Cryptocurrency Fundraising.(2025). Congress; Roul, A. (2024, October 4). The rise of Monero: ISKP’s preferred cryptocurrency for terror financing. GNET.↩︎

Admin, S. (n.d.). FATF warns of emerging terror financing risks in digital era. News on Air.↩︎

FATF urges stronger global action to address Illicit Finance Risks in Virtual Assets. Fatf-Gafi.org.↩︎

Hussain, A. (2015, September). Crypto Payments Uncovered In KP Terror Network. Pakistan Point.↩︎

Fair, C.C. (2014). Fighting to the End: the Pakistan Army’s way of war. Oxford University Press.↩︎

Chakraborty, D (2025b, July 11). Crypto, crisis & the Trump connection: All about Pakistan’s new Virtual Assets Act. ThePrint.↩︎

Sohail, A. (2025). Combating Terror Financing in Pakistan. Issra.pk.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Crawley, J. (2025, July 3). IMF turns down Pakistan’s proposal to subsidize power for BTC mining: reports. CoinDesk.↩︎